Since I was in high school it feels as though it’s once or twice a month I read that there’s a ‘new fastest car’ that is either being built or has just bested its class record at the Nürburgring.

Fast forward to last week and it was me writing that I saw the new fastest RWD car in the world breaking records at the Never Lift Half Mile. Meanwhile, around the globe on showroom floors 0-60mph times have dwindled to nothing, and supercars comfortably make 900hp in the current automotive climate.

With manufacturing processes and material science converging with innovative ways to extract power from a petrol engine, it seems as if we’re in the golden age of horsepower and, thus, top speed. The fact that you can purchase a Corvette from the factory today with more power than the V12 Enzo of last decade should excite you very much, but there’s obviously so much more to the equation of speed than this one number (spoiler alert: this one number for the Malone Racing C6 is roughly 2,800hp, but more on that in a moment).

This is particularly true of lap times, of course, and while it seems the rulebook would be completely thrown out when it comes to straight-line, high-speed shootouts, I learned otherwise at the Never Lift Half Mile. Instead, there’s an entirely new rulebook that comes into effect on the airstrip.

As you would expect, a lot of the characters here are familiar ones: grip, drag, gearing, horsepower, and so on. But with all this talk of more power and faster cars over the last decade one might think that designing for top speed would be a piece of cake by now.

But this just isn’t the case, with many factory manufacturers abandoning outright speed in favor of other more marketable attributes. This is even the case in supercars, which really begs the question: has top speed all but become entirely irrelevant?

Acceleration is a much more relatable datapoint for a designer to target; it’s something we can all reasonably experience in our day-to-day driving when we decide to mash the pedal into the floor. I can say with great confidence that while we have surely all felt our car’s maximum acceleration, the majority of us just haven’t had the opportunity to experience its top speed.

It’s this delicate balance of top speed and acceleration that really drew me in to each and every run of the weekend at Motovicity’s Never Lift Half Mile. Initially, drivers have to find every last bit of traction possible as they pull off the line and shift through the gears. But after the quarter-mile marker, it really becomes an insane battle against the air around you.

This brings me to what may seem like some mumbo jumbo, but the equation for calculating air resistance is actually really straightforward. If at any time this next bit makes you want to punch me in the face, just read the last sentence of this chapter and move forward.

Without regard to units, the equation for the force of drag is simple: the density of the medium you’re traveling through (obviously air, in this case) times the frontal area times the coefficient of drag times your velocity squared. I was able to find a few numbers around the internet for the C6, but I have to take them with a grain of salt as these sources were conflicting.

While the drag coefficient of .36 seems high, it checks out since the designers of the C6 had to do a bit of trickery to make sure it sticks to the ground at its factory capable 200-or-so-mph. The frontal area I found of 22.3 square feet seems within reason, so I went ahead with these numbers. Even if they’re a bit off, it should get us right in the ballpark of what we’re looking at moving from 100mph to 200mph and on up to 235mph.

It gets too messy converting units to arrive at horsepower, so I won’t bother explaining this bit, but the results are in line with what you’d expect if you’ve looked into this before (there are a number of online calculators you can play with if you never have). Theoretically, it takes less than 65hp to go 100mph in a 3,300lb car, while 200mph requires over seven times as much at roughly 460hp. Finally, the 6mph jump from from 230mph to 236mph requires almost as much additional power (roughly 55hp for the differential and over 750 total) as it took to get to 100mph in the first place, and each mile per hour added on thereafter adds at least 10hp.

Of course, it would take miles to actually reach this speed in a car with this much power — and there are other factors in the real world such as drivetrain losses, wind speed, and so on — but it gives you an idea of the challenge that air alone presents. So, what did it take for Morris Malone to reach this speed in just half a mile?

CHAPTER TWO

Anatomy Of A Half Mile Car

I’ve already ruined the surprise of one magic number in this build, which is horsepower. Morris tells me that their MoTeC told them that power at the crank peaked around 2,800hp over the course of the weekend. Factoring in drivetrain losses through the Corvette and to the back wheels and we’re still over the 2,000hp point by a few hundred.

This is made possible with a huge — although not as massive as I would have thought — 400 cubic inch Dart LS Next block from Late Model Engines out of Houston, Texas. So, that’s nearly 6.6L to start with and it gets more insane from there. Seeing as how the motor happily revs out to 9,500rpm, Edelbrock LS-R canted-valve heads have been chosen to handle the abuse.

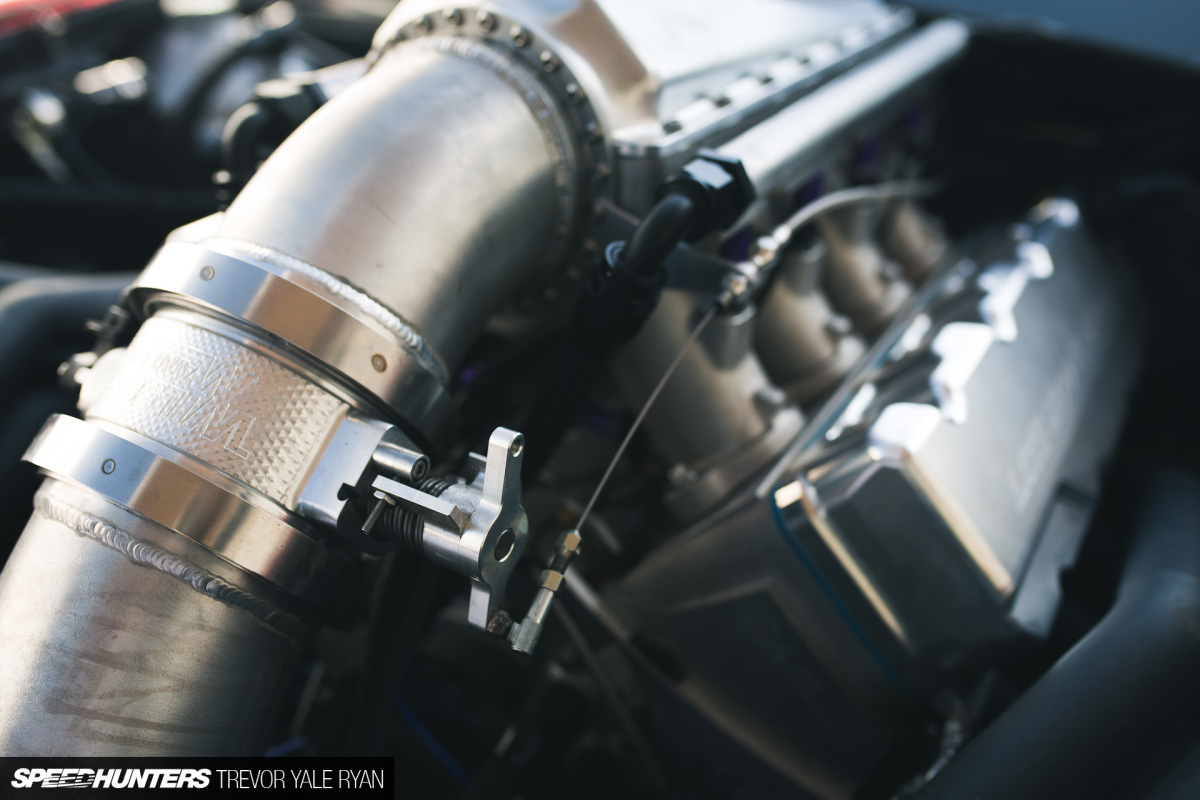

Next in the equation you’ll find two 88mm Gen 2 PTE Promod turbos at the front of the car smushing air into the one-off Mast Motorsports intake that includes cast aluminum runners directly into the heads. You’ll notice that there aren’t any intercoolers on the car, a feature that comes down to the choice of fuel which I’ll dive into shortly.

With the twin turbochargers tidily tucked into the one-off front bumper you don’t quite get a sense of how huge they are, but the immediate exit the exhaust takes helps bring it back into perspective.

Have a listen to the last start-up of the weekend as the Malone Racing team tucked the car away into the trailer for the long ride home to Washington state. I will say, with the ridiculous wind it just doesn’t do it justice; proof it’s high time to invest in a proper mic and learn new things.

Back on topic, 400ci and twin 88mm turbos on high octane just wouldn’t be enough to get into the 2,000hp to 3,000hp range. It’ll get a bit nerdy again for a moment, but if you aren’t aware of exactly how methanol is capable of supplying so much more energy to the wheels it really is fascinating. Again, if reading this incites any feelings of waiting to cause me pain, just gloss over the next two paragraphs and keep rolling.

If you look at it from a material standpoint the energy density (in MJ/m³) of methanol is significantly less than that of gasoline at roughly 18,000 and 34,000, respectively. If you want to think of energy density in a simple way, this is saying that burning a certain volume of gasoline will always release nearly twice as much energy as burning the same volume of methanol. So, it doesn’t immediately follow that methanol would be an advantageous fuel here.

But if you dig deeper into the chemistry, the way that the methanol (CH3OH) mixes with the oxygen (O2) in air when it burns is what allows you to absolutely pour on the power. Generally speaking, and simplified a bit, the chemical product of combustion is always carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). Obviously, matter itself is neither created nor destroyed in the process of combustion so to keep this equation balanced you don’t run anything close to your typical 14.7:1 ratio of air to fuel.

Instead, John Reed Racing has been able to tune for a ridiculous seeming two-to-one air-fuel ratio with methanol flowing through the Malone Racing C6. So, while methanol itself actually has less energy ‘inside’ of it than gasoline, the key is the sheer amount of fuel you’re able to shove through the motor at any given time. Just for a little more perspective, under load the thirsty motor will drink down 13 gallons of methanol per minute.

This is made possible with John’s MoTeC M150 package and firmware the C6 uses, but his kits certainly aren’t limited to half mile cars; you can learn more about these kits on the John Reed Racing website. And while you’ll find that John is based up north in Oregon, he’s always down to fly out when the Corvette is running.

The next variable in the ever-complicated equation is grip — actually delivering this 2,800hp to the tarmac is an entirely different game than making it in the first place. First off, after power is sent though a (rear-mounted) RPM Transmissions TH400, which includes a CNC-machined ProTorque converter, it finds its way into an IRS axle in the back end of the car.

The fact that they’ve retained the independent suspension out back is super surprising to me, but the RPM Transmissions Ford 9-inch differential is more than capable of transferring power out to the massive Mickey Thompson ET radials. While bias ply slicks would allow for a harder launch with their soft side walls, the radials provide the necessary stability for the long half mile runs.

As you’ve probably come to conclude it’s clearly a balancing act to get the car to speed at this distance, and as such I was surprised to find the interior mostly intact. The Racetech buckets, while cozy, are actually remarkably comfortable in this car; I fit surprisingly well.

So well, in fact, that I need to tell myself not to go searching for a C6 to replace my poky 10AE Miata…

Next up in the anatomy of a half mile car is the aero, which — especially if you read my rambling bit at the beginning of this piece regarding air resistance — you’ll know is extremely important. After a run well into the 200s, Morris was just a bit too hard on the brakes, causing the start of the smooth underbelly to destroy itself at speed.

His father, Morris J. Malone, was quick to put it back together and it just shows how getting this car to these speeds requires a huge human element working in harmony with all things mechanical. You’ll also notice above that the massive Caliber Customs diffuser out back has also been ground down a bit from the airstrip; while this is something to look into, it’s mostly a non-issue at this point.

On the topic of the Malone family, Morris J. himself is far from a pampered racing driver. After each run he was working hard getting the car ready for the next pass; refueling, swapping filters, and so on. It’s a monumental task.

FINAL CHAPTER

Breaking Records

Of course, the Malone Racing C6 was out at the Never Lift Half Mile to prove itself. While the car has only made around 30 passes to this date, it’s insane to realize the records the team has to their name at this point.

This isn’t to say it’s been easy, though, as Morris and the crew have been working on the Corvette for nearly four years to become the fastest RWD half mile car in the world.

At the end of day one, the C6 was sitting on a best run of 217mph. While I thought this was quite good in its own right, Morris said I should expect to see them in the high 220s on Sunday.

I thought this seemed really optimistic, but I was promptly shown what Morris is made of the next day. After multiple passes in the mid 220s, Morris blasted on to a hair over 232mph to become the fastest-ever Corvette in the half mile.

Talking to John Reed and Morris, it sounded like they weren’t going to find anything more in the motor this weekend, though. Maxed out at around 2,800hp, the injectors just didn’t have anything more to give.

When John explained that each half mile pass requires around 1.7 gallons of liquid gold, I was impressed that any conventional-seeming injectors are capable of this in the first place.

But not content to end the weekend with one world record, the team looked into the aero to see what else they could find.

While you might think that big aero is counter-intuitive on a build like this, it’s absolutely critical for stability at these high speeds. Rather than doing anything drastic to the setup, the team simply removed the top element from the GSpeed wing and taped up the front end of the car to see what would happen for their last run of the day.

You may have noticed that some stickers were placed on the back hatch at this point, which I’m pretty sure helped, too…

This time around, Morris went in for a burnout to get his tires nice and sticky for the final pass. This was his only burnout of the weekend and it was quite dissatisfying to witness it from over a half mile away.

But with sticky rubber, a taped up front end, less one element in the rear wing, plus two Speedhunters stickers on the back hatch, and with the driver side window falling down at some point after the pass, the Malone Racing C6 became the fastest RWD half mile car on Earth.

236.10 miles per hour (379.96km/h) in the space of just 2,460 feet (750m). Pure insanity. While the all-wheel drive record is still some 20mph away, Morris told me that he doesn’t believe they’re even close to the ceiling yet. His favorite aspect of this car is the fact that it is RWD and he says he’s not about to jump on the AWD bandwagon to power his way to yet another world record.

He’s one of very few drivers who have taken the time to set up a C6 for this type of racing and he plans on continuing to push the envelop for the RWD platform. Together with Matthew Lambrecht from Caliber Customs and John Reed Racing, I’m confident the team will do just this.

Not alarmingly, 236.10mph was good for the fastest time of the weekend, as well as plenty to win the RWD class on Sunday. Morris took home the same check the previous day, joking that he didn’t know what to do with all these big checks. Just figuring out how to hold them up for a photo was a procedure in itself.

John Reed set him straight pretty quickly on the matter of the newfound cash, referencing those topped-out injectors that they found need to be upgraded. I heard someone say “easy come, easy go,” as they laughed on their way back to the paddock to pack up for the weekend.

From the first moment I spotted this car, I knew it was the quintessential straight-line speed machine; the one to watch that weekend. What I didn’t know is that it would literally become the fastest RWD car to ever complete the half mile. For the first event after putting the car together going home with a trio of trophies and a pair of world records is certainly not a bad outing.

They’re far from finished, though, and Morris will be back at in Colorado later this year. If you can’t make it out to the event, you can still follow the Malone Racing team on their quest to 250mph (402km/h).

Or will they go even faster than that?

Trevor Yale Ryan

Instagram: tyrphoto

TYRphoto.com

fastest thing I have been in made 1,600whp and 1,400tq. Can not even begin to imagine what adding another 1,200whp would do. madness.

Haha I know right? I'm pretty sure the car is good for a bit more than that, too. Madness indeed.

And to think in high school I thought Honda Civics we're fast...

They are compared to a Huffy.

You also probably used to think high school girls were hot...

In both cases, it'd be in your best interests to move on.

"This is made impossible with a huge — although not as massive as I would have thought — 400 cubic inch Dart LS Next block"

I'm sure you mean POSSIBLE?

Methanol burns at a 4:1 ratio a:f on the rich side. It's not just used because of the energy it expends but because it cools the combustion charge as well. That's the really important bit to mention.

It's actually in the same family so to speak as ethanol and can burn so cool that intakes are cold to the touch. Be careful when you stand behind cars that run on methanol at a race as the fumes can cause you to pass out!

True!

Some people here might be asking why tuners don't use nitromethane if methanol is so great. Why not use what the top fuel guys use?

Well, the simple answer to that would be that nitromethane is so volatile it rips shit apart which is why NHRA guys are rebuilding stuff as often as they do. Nitro is actually very dangerous to inhale. Produces tons of energy at the trade off of wrecking parts fast!

I heard only pussies run NitroMeth...

Did you hear that from a licensed OB/GYN?

More maths please

I quit my engineering job for a reason pal. I actually quite enjoy maths though and on a car like this the numbers become a bit staggering.

Ah engineering isn't so bad. All you really need to know is F=ma and you can't push a rope. Everything else is minor details ;-p

I hate to be "the guy" who suggests putting down the Bud Light and getting some quality craft beer...or a good scotch.

However, it may be time for these guys to move on to aviation.

Oh, and the prize money is laughable. If your build gets to the point where you're winning at events like this...$2500 ain't doin' much.

You can give me your winnings then mate, that's a trip to Japan or two weeks in Hawaii...

As an engineer you should know that it's "relatively" nothing, It may cover the fuel and tires expenses only (if not just a part and not full expenses) and sure better than nothing specially with "1st" written on them. The guys already sacrificed a lot of human power and money and going to the next level (sure there is a next level somewhere) a sponsor is a good call even if i think the guys want to keep to the family (sponsor names will always steal the lights).

And btw, a 2 to 1 ratio is fkn sick (in a good way).

Right? $7500 is a good hunk. pays for alot of stuff to keep the car up and going

Sure, I think what he means is it isn't shit in relation to what people spend or output to get there which is usually the case 99% of the time in motor racing.

One thing you have to admire about anyone who pursues this sport is we give a lot more financially than almost any other sport on the planet in terms of recreation. Nature of the game...

nerrrrrrrrrrrrrrdddddddddddd

Running no intercooler will also drastically reduce frontal area so it makes sense to go with methanol.

Frontal area doesn't reduce by not having an intercooler. An intercooler takes up part of frontal area. You're confusing drag points with Fa....

Will they be running at the Pikes Peak Airstrip Attack?