It’s interesting how much emotion we ascribe to our senses, and the effect it can have when a particular input is impaired or reduced. Dial in some preconceptions as well, and the prejudices can come thick and fast. Take the general reaction to electric-powered cars. Where’s the noise gone? How can something that doesn’t howl like a banshee and isn’t powered by constant explosions be any good? After all, milk floats use batteries, not performance cars…

Can I deny that I didn’t think along those lines when the pious Prius started hitting city streets? Or when race car prototypes boasted of being able to, well, maybe make it the length of a pit lane before they ran out of juice? My own personal juices were not exactly flowing at the prospect.

Then things started to change. Hybrids have quickly become de rigeur for high end hypercars, F1 has KERS and then there’s the Le Mans 24 Hours. That’s where things get really interesting. Seeing a Toyota TS030 Hybrid spectrally sliding away from the garage, or an Audi R18 e-tron quattro sci-flying through corners at unfeasible speeds is a truly emotional experience. There might be no engine sound, but there is undeniably a great noise. If anything, there’s a purer sound. The sound of ripping air and the tenuous contact of rubber with tarmac.

With the Drayson Racing Technologies Lola B12/69EV, you won’t believe your eyes, yet your hearing will still be intact at the end of the day.

These days we need to recalibrate what we think electric drivetrains are capable of – and more importantly embrace what an incredible effect this technology will have on the cars we’ll be driving in 15, 10 or even five years time. I love the sound of a V12 as much as any petrolhead, but maybe we need to change the terminology. Can you also be a batteryhead?…

Drayson Racing Technologies are certainly aiming to persuade people that way. Having witnessed their Lola in the flesh and now up close, I would defy anyone to not admire what this car represents and how it performs. You want neck-snapping acceleration, unreal levels of torque and obscene top speeds? Then this is the car for you.

How about these headline stats: 0-60mph in less than three seconds, 0-100mph in five seconds, a top speed of 225mph – and rising, 4,000Nm of torque, throttle response that’s on a different planet. It’s cutting-edge technology wrapped in carbon fibre; an electric shock to the senses.

In the space of just two years, Drayson Racing have taken an old LMP1 prototype, stripped out the old 5.5-litre Judd V10, replaced it with a full electric drivetrain and made the fastest EV on the planet. One that will pull to over 225mph.

http://youtu.be/4pbmbX6KuO4

In the last six months, Lord Drayson and his team have smashed tomes-worth of records for electric-powered cars: top speeds, standing quarters, flying mile and kilometre runs… The achievements are impressive in their own right, but it’s still the fact that the Lola is a stunning driver’s car that’s the important part of this.

The previous Land Speed Record for Electric Vehicles was set back in 1974 – the General Electric Battery Box set the marker at 175mph. So it’s been a while. But Drayson didn’t just raise the bar a bit. They smashed the existing record, sustaining 204mph over a mile back in June. And then just broke it again recently, to be sure. And aim to continue the increases in 2014.

There’s a precedent for this. The first overall Land Speed Record was set by an electric-powered car back in 1898, as were the second and third records. Steam even made an appearance before the internal combustion engine took over in 1902, though it was steam that took cars over 100mph before petrol-driven vehicles. Are we just seeing things come around again?

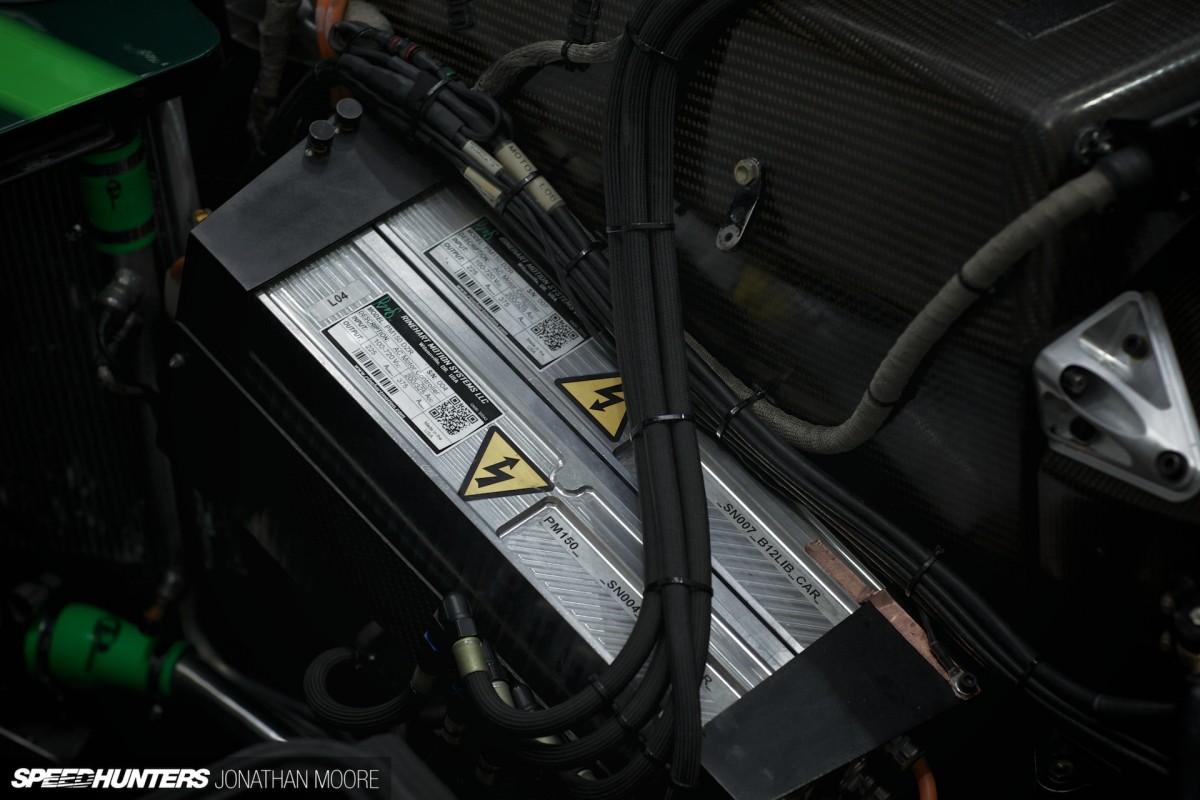

Look in the back and tell me it doesn’t look right. The packaging is exquisite.

That Drayson Racing have gone from a standing start with this makes it even more impressive. With no major manufacturer support remember: this is a pure privateer effort, there’s no Audi or Nissan bankrolling this. The car came together in just six months, and most of that time was spent planning before a single screwdriver was lifted or piece of metal cut.

If you want to make a fast car, it’s good to start with a car that goes fast. As a proven contender in the privateer LMP1 ranks, the Lola was definitely ticking that box. Drayson bought the B09/60 chassis towards the end of 2009 – within four weeks of putting down their money they were shaking the Lola down at Silverstone, and then shipped the car straight to Japan for the inaugural round of the Asian Le Mans Series, where they set pole position.

The Lola also competed at Le Mans the following year and won the American Le Mans Series race at Road America, which was the first victory for a bio-ethanol powered car, along with scoring a number of poles.

CHAPTER TWO

Apply current, stand well back

Although the Lola was an efficient petrol-powered racing car, it was hardly somewhere you’d start if you were attempting a wheels-up design for a new EV. But with the success of their bio-ethanol programme, entrepreneur and team owner Paul Drayson decided to start a new company focusing on all-electric drivetrains – and the Lola was chosen as the testbed. We’ll have an interview with Lord Drayson here on Speedhunters in the coming week, which I think makes for thought-provoking reading. He runs the team because he loves racing, and he gets to drive the result.

The question Drayson were asking was what would a 200mph electric car sound like? Starting with the Lola, a whole load of experience with petrol-driven racing cars and a new team of electrical specialists and software coders, they got to find out.

Whilst Lola modified bodywork, Drayson concentrated on the driveline, which not only included the hardware but all of the software coding as well. That it looks so tidy is a testament to the work they put in. The difference in concept couldn’t be starker. Drayson Racing’s Chief Engineer, Graham Moore, describes it as ‘pretty tidy’, which is a pretty huge understatement.

The big V10 is gone, replaced by a substantial carbon box that contains the batteries. The box is a part of the crash structure – the team think it might be the only electric competition car with a battery compartment as a stressed member – and contains up to 300kg of modular batteries, which is almost a third the weight of the car. Interestingly, the Lola is fitted with a wireless charging system which sits low down on the floor.

Taking out that V10 meant starting from scratch with the back end. There were a lot of compromises, and in fact the team started with four options before settling on this packaging arrangement. The drivetrain series is easy to explain but naturally far more difficult to get working: the battery supplies high voltage DC, the inverters converts that to AC and supply it to the motors.

The spinning heart of the Lola EV has to be pointed out. The four YASA-750 Advanced Axial Flux motors are surprisingly small, and hide in the centre of the car underneath the suspension system. 25kg, 350mm in diameter and only about 60mm wide, the motors are paired up and power the left and right wheels respectively. These are little electric beasts: one motor alone reached 250hp on the dyno.

They’re mounted slightly forward of the axle line for packaging reasons and better centre of gravity, and a drop gear is used to reduce the speed of the energy transmitted to the driveshaft. An electronic diff controls individual wheel torque requirements.

The inboard suspension is pretty much as per the original, and in combination with the shape of the engine deck, was another thing to influence packaging. The pickups would originally have been off the magnesium six-speed gearbox, but now attach to a replacement carbon structure above the motors.

Not only is the geometry retained, but even the overall weight has hardly changed from the petrol-powered predecessor: the LMP1 weight on the start-line would be about 970kg and the EV version tips the scales at 995kg.

EVs do need some cooling, although they are very efficient compared to petrol engines; perhaps five percent of the 850hp produced is lost in heat, compared to around 30 percent for an internal combustion engine. The radiators have been left in their original positions and two cooling circuits installed, one oil- and one water-based. The water/antifreeze mix in the thinner pipes cools the inverters; the oil system cools the motors.

FINAL CHAPTER

All torque, no drag

Although the Lola retains the outline shape of its LMP1 origins, the body is a fundamentally different thing now to how it was in its racing days in performance terms. Except for getting off the line, grip is almost irrelevant and drag is even more of an enemy. Downforce has been shorn off in the hunt for speed, with all intakes and louvres covered up and mirrors removed. As the speed creeps up, that drag makes eking out every single mile per hour more and more difficult.

The front aero is the challenge, as at least with the rear you have wing elements to play with. So, all the topside brake ducts and even the front diffuser have been blanked off, and the fences and infills underneath altered.

The original nose intake has been covered over and a small blade added for cutting the timing beams on speed runs.

The Lola is fitted with variable aero front and back to keep the car balanced, retractable dive planes and a moveable gurney respectively, controllable by the driver from the steering wheel: the now defunct paddle-shift is used for the task. A massive 30 percent reduction in drag is achieved.

With the sad demise of Lola, Canadian specialists Multimatic stepped into the breach and developed a new aero pack in tandem with BAE Systems that’s seen the car take a leap forward, specifically the rear wheel cowls and wing assembly. The middle element is actually from the car’s run at Le Mans in 2010; the end plates show the hammering the car gets doing high speed airfield runs.

A useful adjunct of the LMP car spec is that the nose and tails are single pieces that are easy to swap, making aero changeovers quick to achieve. The original wing shows a much more standard LMP look, although it was also a bespoke part and fitted with a moveable flap.

The low-drag aero pack was actually developed for an aborted run at Bonneville: flooding meant the attempt was called off, but the Lola has recently run again in the UK, where the new parts showed their potential.

What they need now is a longer run: at the moment they’re not entering the timed section at vmax, although they’ve been hitting 219mph at the final beacon before having to brake. But to achieve what they have on a 1.8 mile airstrip? It’s no mean feat. With only 0.4 of a mile to accelerate the car up from a standing start, the Lola is at 195mph when it hits the first beacon. Traction control improvement have helped further.

Oh, and there aren’t any rear brakes. Even the front brakes were removed for the long runs at Bonneville, as the motors supply braking force. Still, when the end of the Elvington runway starts screaming up, I’d probably start praying for that set of disks to magically reappear…

Inside the cockpit is far less cluttered than in its LMP1 days. Gone are the majority of radios, batteries, air con and other ancillaries, and in its place instead, a simple set of switchgear.

They have their own bespoke carbon steering wheel that they developed with Cosworth (who also supply electronics) with a comprehensive display linked to the sensors – of which there are many.

It’s an engineer’s dream: thousands of embedded sensors measure every part of the system. Currents, temperatures and voltages across all the drivetrain, both for performance and safety monitoring. The safety system is incredibly complex and took up a fair part of the planning process for the entire project: automatic shut-downs for certain elements and lock-outs for others, so you can’t set fire to an inverter or blow up a battery.

There are three big red emergency stop switches to disable the robo-car should things go wrong, one in the cockpit and one on each front fender. Marshals are given full briefings on how to safely deal with the car before any runs.

One thing that is seriously taken care of is the idea of the car getting fired up and then merrily driving off on its own. The driver has to physically enable the high voltage system and then press the brake and wheel buttons before being able to engage the drive. That was just one of a whole set of scenarios that the team had to adjust to from their years of racing ‘normal’ cars.

But what is normal? Drayson’s Lola EV is currently configured to be able to run two racing laps on the Silverstone Grand Prix track – and at a faster pace than the V10. It’s all down to battery capacity, which is exponentially improving year on year. Things are likely to leap forward, with the input from both Formula 1 and the new Formula E series. Drayson aim to continue developing their Lola, so even greater levels of performance are likely in 2014. The world is changing. It might be getting less noisy, but I think it’s definitely going to be no less exciting.

I think chris harris drove this car

ok im a noob i opened my mouth before i got to the end disregard....

this car is beast

This car has made me like electric racecars

I'm left speechless lol.

Always exited about electric race cars. Great article!

Thanks for this! I found myself right clicking and saving pictures of wires and control boxes : 0

Thats a weird feeling knowing Im excited by stuff I have no clue about...I guess that makes me

a plug-head?

Hey speedhunters, great article about a car i had no idea about. PLEASE keep showing people that electric cars are the future. Only a fool would think that revolution isnt necessary, and sadly there are so many people that will stick to the old way. I mean this car has 4000 Nm of torque?! Thats insane! Thats gotta be the highest torque rating a car on this website has got! Make that a point, i like the title, its a nice play on words. But you can actually develop this industries interest to the young market by exciting them more.. instead of the jazzy title, more people would click on '4000Nm torque! Feature Car record' or something similar ya know.

netflix has this documentary about electric bikes racing at the manx tt

and the weird stuff that happens... for example, when on public roads

normally lined with birds, they usually move when they hear a bike

coming its way, however with the electric motorcycle, they have no idea

whats coming so they just stay put. i wonder if the same goes for the

electric car??? btw this article is awesome. its amazing that a new

electric car is out there making some noise... or not lol. and the fact

there are no brakes????? mind blown. wireless charger... ditto. the future of racing is evolving. maybe we'll see a running model of the x1.

anyway, i'm all for electric/hybrid/plug-in, bio diesel, diesel, ngv,

and e85 cars. we need alternative fuel's if we are going to enjoy

motorsports in the future.

d_rav when you release the "throttle" of an e-car, the current also being cut down, and it gives the brake effect. if you still confused, try to search about electric motor.

nepias that's typo, it's only 400Nm torque. But it's awsm number for an e-car

muhammadilham nepias No, it isn't a typo, 4,000 (four thousand Newton meters) or 2,950 pound feet of torque. Granted that is at zero rpm which is where electric motors get all of their torque due to being at stall condition. And that number goes down as rpms go up. You may want to look at the Rimac Concept One. Similar numbers.

This thing is absolutely bonkers. I love it, and I love that it's an entirely privateer effort.

This thing is absolutely bonkers. I love it, and I love that it's an entirely privateer effort.

I fell in love with this amazing machine after watching Chris Harris take it around the track. Insane.