What do you do when you meet your hero? Do you talk to them, say hello, shoot the breeze, or stay at a distance, just hoping to catch their eye for a subtle sign of recognition? What if it’s an inanimate object, like the McLaren F1? Then things can get really weird… especially if other people are present.

There are a number of cars that still stop me dead in my tracks, and this is one of them. Since its release, my love list has included the McLaren F1, in any and all of its guises. I might have lusted after the Countach, collected dozens of Matchbox Porsche 911s and had my brain overloaded by the Porsche 956 and Lancia LC2 Group C cars when I was a kid, but the F1 launched at the perfect time, hitting me squarely in the sensory overload portion of my brain just as driving was becoming a fundamental part of my life.

I’d rediscovered Le Mans specifically and sportscar racing in general (having repeatedly stayed at a hotel on the Hunaudières straight on family holidays through France as a child), but here was a car that was overtly, deliberately a road car first and a racer second. That seemed improbable: there are so many cars released ‘for the road’ which have been nothing more than to tick a homologation box for a racing programme, resulting in admittedly exotic but completely out-there cars which were barely fit for purpose. But the F1 was different. Even if I knew I’d likely never drive one, the F1 seemed somehow more… of the people. Less ostentatious than other supercars.

The idea of a favourite supercar is a subjective thing. With so few of us having the opportunity to actually drive one of these mythical machines, we have to base our opinions on what we see with our eyes, mostly through photographs, and perhaps in combination with what has been written by the lucky elite who have got behind the wheel (and subsequently pressed the starter and hit the throttle, I should add).

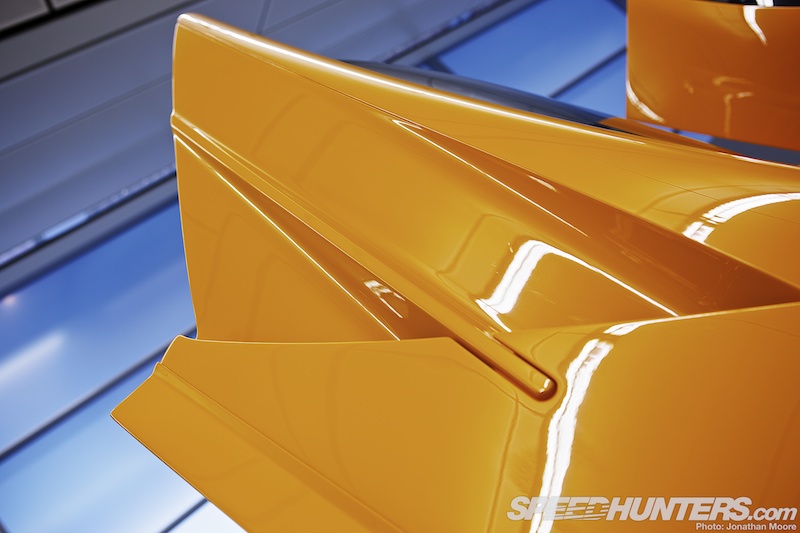

This doesn’t downplay our involvement with them though. Supercars are works of sculptural automotive art, after all, and not only can but should be appreciated aesthetically as much as from a driving standpoint.

Every so often you get the chance to see one up close. A motor show like Geneva perhaps, or a festival like Goodwood. You can then engage with the car on another level: appreciate the quality of both design and construction, and if you’re lucky add a second aural level when you hear the engine turn or even a third visceral level when you see and feel it move.

We’ve previously looked at a number of supercars from the 1970s, and you’ve discussed at length what makes a supercar in the comments of Mike’s post. I don’t think there can be any question that the McLaren F1 is a definitive supercar, up there in the annals of all-time greats. If the Countach made the ’70s its own and the F40 the ’80s, then perhaps the F1 can be said to be the supercar of the ’90s. The last of the true driver’s cars, an organic joining of eyes, hands and feet to engine, rubber and road.

I’d had two previous experiences with this particular car, but they were glances exchanged across a room compared to the amazing access we got for this shoot. Firstly I’d seen it during the launch of the MP4-12C back in 2010, gently rotating behind glass in its own protected enclosure. Let’s face it, I wasn’t the first to be smitten by XP1 LM’s ample charms: this is the car Lewis Hamilton lusted over since his first teenage visits to McLaren HQ, and the one promised to him if he delivered back-to-back F1 World Championships (much as I like Hamilton, I’m glad he didn’t win for the selfish reason of this shoot).

More recently, XP1 LM was brought out into the wild for the Geneva Motor Show, to provide a direct and overt emotional link between the new P1 and the original McLaren road car. It was a brave move, made braver by XP1 LM sitting in an angled cut-out of the McLaren stand, just waiting for a hapless VIP guest to fall into the loving embrace of its carbon bonnet (which several almost did). It survived both Geneva and the guests, and here it was, just for us.

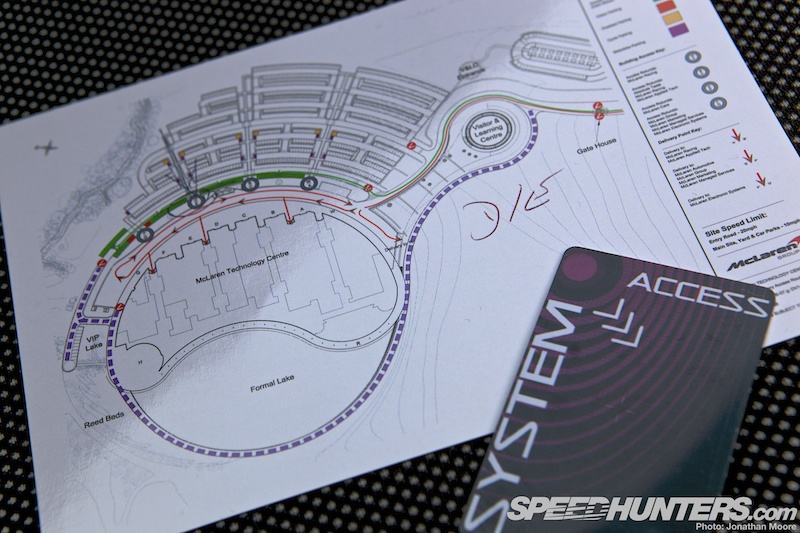

Let’s back up a bit. An enjoyable part of this particular liaison was the build up to seeing the car in the stark environment of the McLaren Technology Centre itself. We’ve already visited the MTC before, back for the aforementioned 12C launch and look at the prototype production line, but this time the nature of our entrance was different.

The experience begun at the main gate, where Rod, Suzy and myself picked up specially coded entrance passes that would get us through the various barriers and to our designated entrance pod. With the yin/yang interlocking shape of the MTC and its lake, the normal guest entrance is via a curving path that follows the circle of the lake and delivers you to the main atrium entrance. But for our visit we’d be following the footsteps of McLaren employees, and taking one of the four external rear entrances for staff (and non-important visitors like us) that sat apart from the main building, connected by underground tunnels.

Parked up, the card swiped us through the first airlock, down the helical staircase and into the decompression corridor – for that’s exactly what this is. The fundamental concept behind these long and starkly lit passageways is for employees to divest themselves of the worries of the outside world and to immerse themselves in the day ahead.

The McLaren badge on their shirts has to mean something; pass through the imposing double doors and your focus has to be on the inside, not the outside. There are World Championships at stake, road car customers to satisfy, electronics industry clients to keep happy. For us, it just built the anticipation.

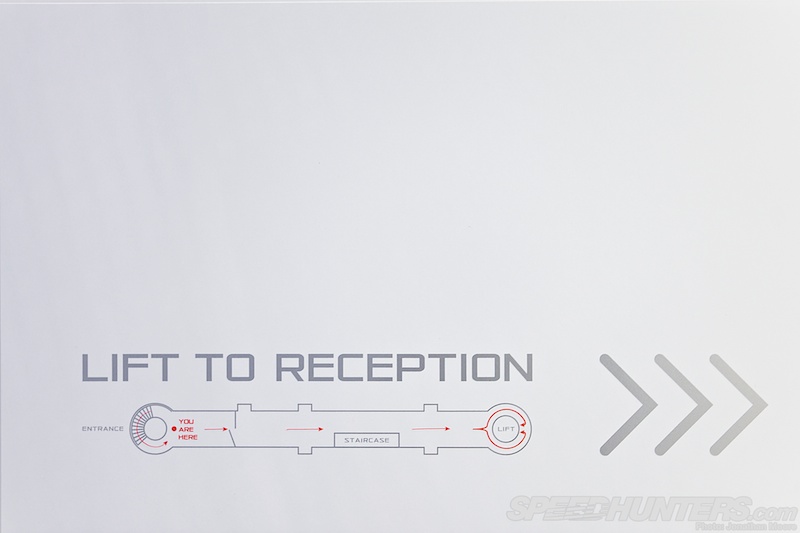

Though being children, we couldn’t help but gleefully pick up on the similarity between the signage and a certain popular computer game…

Especially with this lift awaiting us at the end.

The main atrium was awash with classic Marlboro-liveried McLarens and portraits of their famous drivers: Hunt, Lauda, Prost, Senna… But we had little time to take them in: the F1 we were interested in was downstairs, behind a door with this ominous sign…

The F1 LM was positioned in the same build hall that had seen the initial production of the 12C prototypes – and now housed the P1 line just the other side of a set of dividers, awaiting transfer to the new McLaren Production Centre across the way (more on that facility will be coming up tomorrow). This was XP1 LM, sitting patiently, waiting for us.

We were, naturally, quite excited.

Some even more than me in fact. We had joined the list of those who had sat in an F1. The day could have ended there and we’d have left happy.

This is a privilege, to be dismissed only by the arrogant and the cynical. Back to the art analogy, this is like seeing one of the rarest, most beautiful paintings, but being unmolested by crowds around you. A private gallery, where we had time to drink in all the beautiful detail from every angle as well as the overall timeless design.

XP1 LM was the first of five F1s made to celebrate McLaren’s victory – at the first time of trying – at the Le Mans 24 Hours, a race they weren’t even aiming to compete in. The story had started back in 1988, when McLaren chief Ron Dennis and design head Gordon Murray were sitting in the departure lounge of Milan’s Linate airport. An offhand discussion about designing a road car somehow snowballed into a project proper, and five years later the first F1 was unveiled to a stunned world in Monaco in May 1993.

The car had been hand-drawn rather than computer designed. A coupling of Colin Chapman-influenced light weight and focus on performance, with Murray’s design flair and cutting edge technology, the F1 might not have been designed to chase records but by god it got them anyway.

It had the highest power to weight ratio of any previous production car; the bespoke, 600hp, 6.1 litre BMW engine produced one of the highest specific outputs for a large capacity normally aspirated unit ever made; it made 150mph faster than most cars got to 60mph; the top speed was 240mph; the carbon-fibre tub was a first for a road car; active aerodynamics kept a constant centre of pressure…

Murray was quoted as saying: “It’s not a case of going one step beyond. This is an entirely new starting point for supercars.”

Just as with the recent 12C, the F1 was never planned as a racecar but inevitably ended up as such. Customer pressure led to the 1995 F1 GTR racer, a three-car assault on the BPR series, seven GTRs at that year’s Le Mans 24 Hours and nine cars in total being built. Le Mans fell to the GTR, as did the BPR.

The F1 was now not just the greatest supercar of the decade but now the most successful British sports racing car.

So what to do now? That’s where the F1 LM arrived. Five limited edition roadcars were built, three painted in the papaya orange of company founder Bruce McLaren.

Where the GTR was effectively a slightly detuned road car for the track (though it delivered even more phenomenal performance thanks to its improved aero), the LM would be a barely detuned racing car for the road.

They used the same racing engine but with the FIA restrictors removed to boost power to 680hp – in a machine weighing just 1,062kgs. They were the fastest of any F1 to be made, whether race or road variant.

And what a sound it made, using a tuned quad-exhaust system that made a unique, raucous howl.

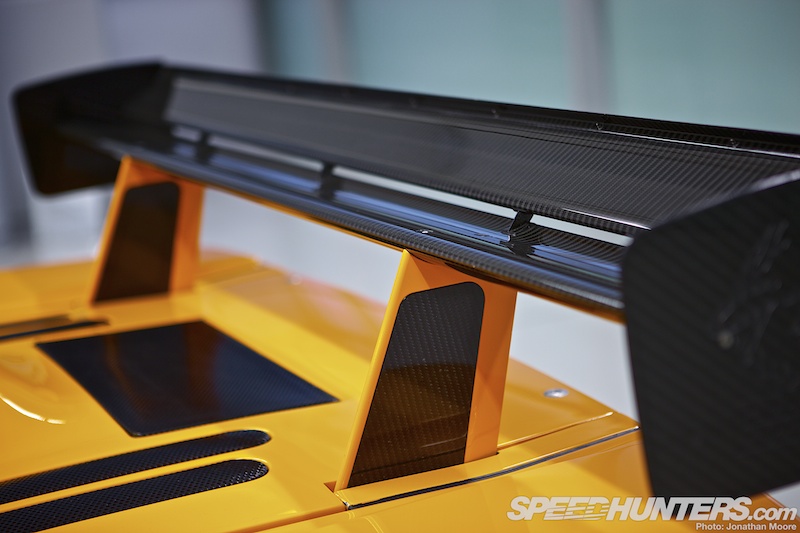

The body retained the full ground effect aero of the racecar: stick a livery on it and a decent pedaller inside, and this would likely out-race anything you cared to match it against, a GTR included.

18-inch Oz magnesium alloy wheels – wider than the standard car at 10.85 and 13 inches respectively – sat in each corner…

…with outboard Brembo ventilated disks (12 and 13-inch) hiding behind the spokes.

The carbon rear wing bore the words ‘GTR – 24 Heures Du Mans Winners 1995′ etched into the endplate.

Inside, the central driver’s seat was carbon fibre with material padding, and both passenger seats were moulded into the monocoque.

The centrally mounted driving position was a stroke of genius, providing optimum weight distribution and visibility. The driver really did take centre stage in every sense.

For your right hand, a stubby, purposeful lever for the six-speed gearbox.

For the left, the functional girder handbrake.

For your feet, these beautiful drilled pedals.

This is what it looked like from the other side of the pedal box at race speed.

The interior trim was minimalist: carbon and Alcantara, though the carbon was allowed an almost decadent lacquer coating.

But this was still a practical car – seriously! The latches in the door sills opened the bonnet (big enough for a helmet or small bag)…

…and the actually quite spacious side lockers that hid in the recesses of the flanks. A screwdriver secured in the aperture underneath the righthand passenger seat was there for opening the rear deck.

Ah yes, the passengers… There are a couple of caveats to the idea that this is a practical car that you drive to the local restaurant or golf club. Your friends will have to be pretty trim for a start, and definitely not have any back problems. It’s snug, to be polite. Standard belts keep passengers in place, as opposed to the five-point harness of the driver. Get the idea that the people wouldn’t ask for a lift twice?

Well, for all the talk of practicality this was still basically a racing car: each occupant had a set of headphones connected to the car’s radio system, which gives an indication of the interior noise. There had been a CD changer in the original road car; here, the music of choice would be the BMW V12.

The LMs are the most exclusive, expensive and sought after F1s. This one is not likely to leave McLaren – it means too much. In 1999, Le Mans driver Andy Wallace took the F1 LM to new records in acceleration, braking and what the human body can endure, going from zero to 100mph to zero in 11.5 seconds and just 852 feet.

Oh, and remember this was a car not designed to go fast. Murray: “It’s just a consequence of the other things it does.”

The shoot dragged on, as I kept finding excuses for just one more shot. Eventually, we really had to go. I’d met my hero, and it hadn’t disappointed. Much as I didn’t want to leave, I didn’t need to look back.

Jonathan Moore

Instagram: speedhunters_jonathan

jonathan@dev.speedhunters.com

McLaren stories on Speedhunters

McLaren Automotive Twitter feed

McLaren Automotive YouTube feed

McLaren is one of my favorite cars. I learned all about the car in need for speed2 & fell love with it ever since. Love the pi too. Great job

Very nice article for the car of the gods OR god of cars!

But I would like to dl the 1900x1200 pictures that would be awesome for my desktop. How can I dowm-nload them?

Thanks for the good read and definitely for the perfect photos.

NVM fellas, found all of 'em

The vehicle speaks for itself.... I feel in love with it after I played the video game REAL RACING 3.... It's a beast, a monster, a car for anyone who likes to fly a plane at low altitudes !!!!

My friend with privately owned F1. .This was fitted out with Le man's parts left from race program at Mclaren a few years ago , engine, aero, you name it been done...and its a daily drive by proud Kiwi owner , Mclarens spiritual home: )

Oh and my friend is only 5'4!!! How low is this beast

Photos taken at 50th Mclaren dealership here in Auckland New Zealand. ..hope you like : )

McLaren F1 is my crush ever since I played Need For Speed 2 back in late 90's...I love this beast and certainly in my head, it's better than Bugatti or every other hyper car

You said out race even the GTR did you mean the Nissan GTR

the best txt full of emotions i ever read just like i wrote for the puries handling car of all time

tnx