During the Edwardian era, First World War technology and ingenuity combined with an insatiable passion for speed, resulted in some of the most unhinged competition vehicles imaginable.

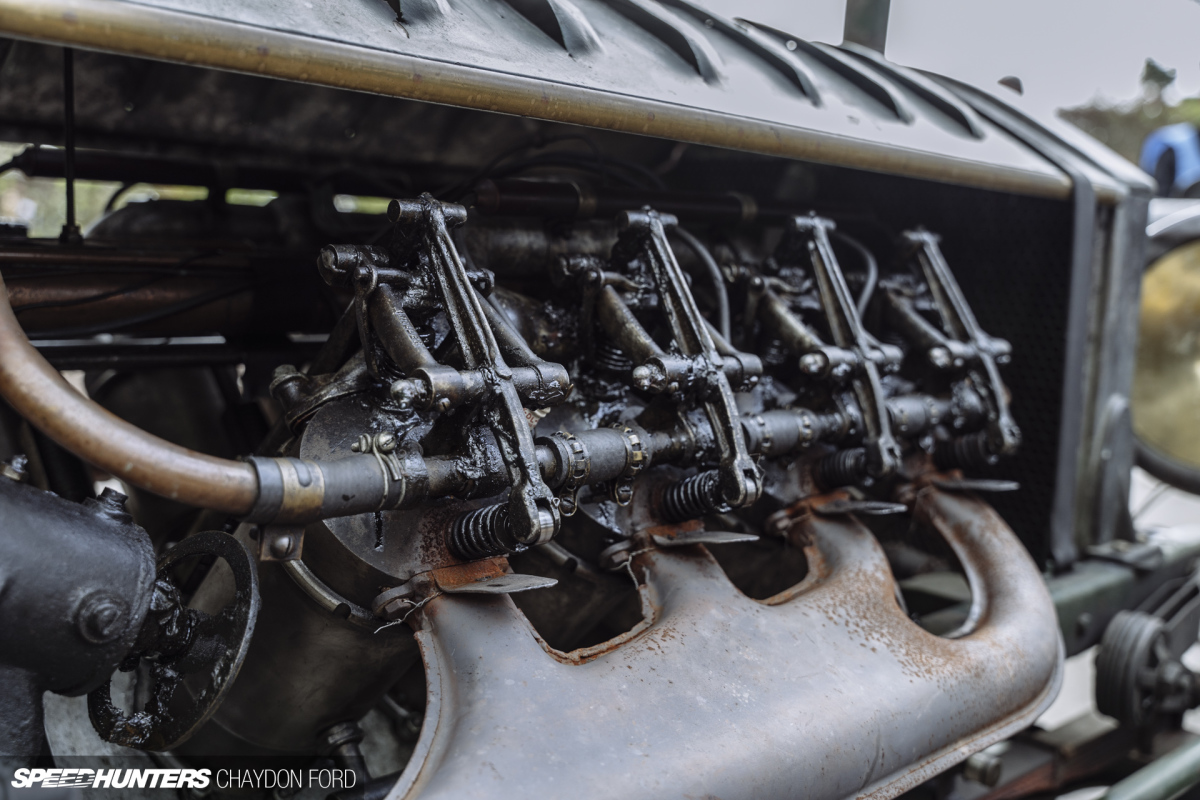

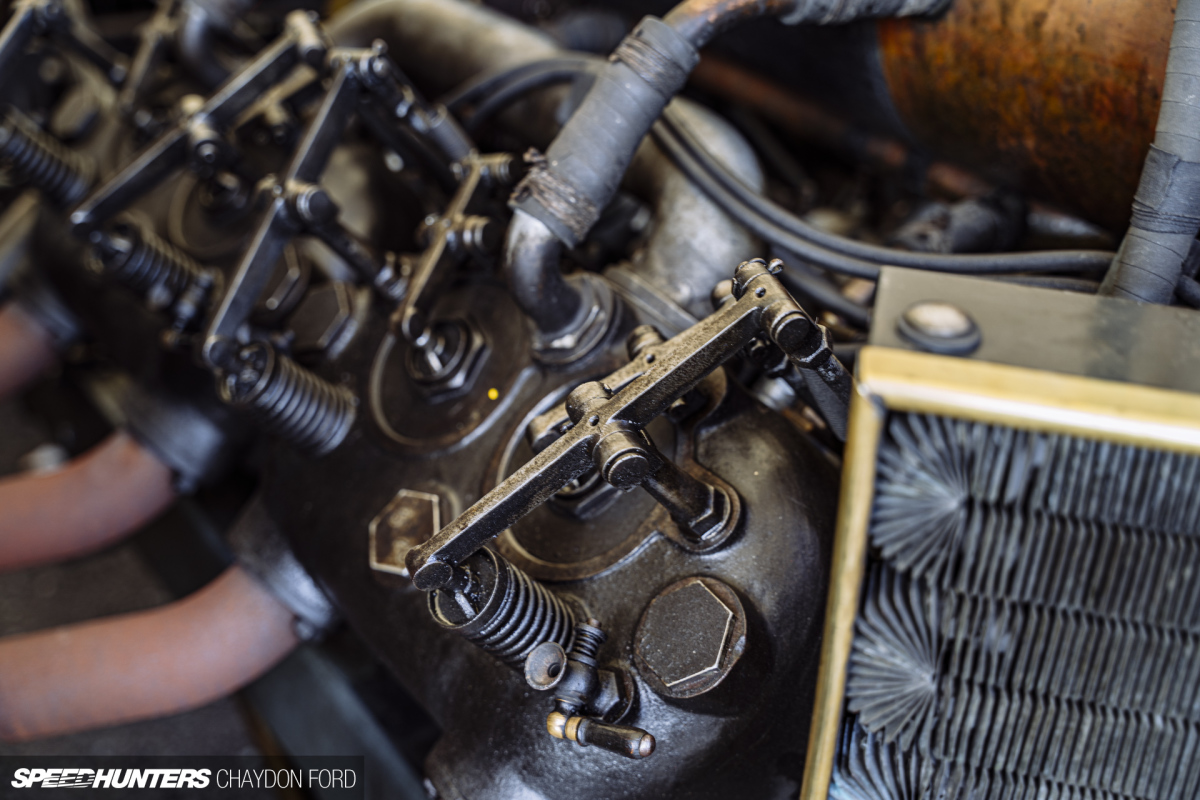

At this time, the most reliable way to make big power was to fit a big engine. While no different to today, in the Edwardian era (classed until the start of World War I in 1914), a big engine was BIG.

Many cars were built by smaller marques looking for the quickest and cheapest way to make power, which is where aircraft engines came in. Find a chassis, find a donor motor, mate them together, piece the rest around it and drive the wheels off it. Groundbreaking for the time, nothing could come close to the speeds these cars were capable of.

Up until the 2024 Goodwood Members’ Meeting a few weeks ago, I’d never given Edwardian racers much thought. At classic motorsport events, I often skipped their races to browse elsewhere. But not this time.

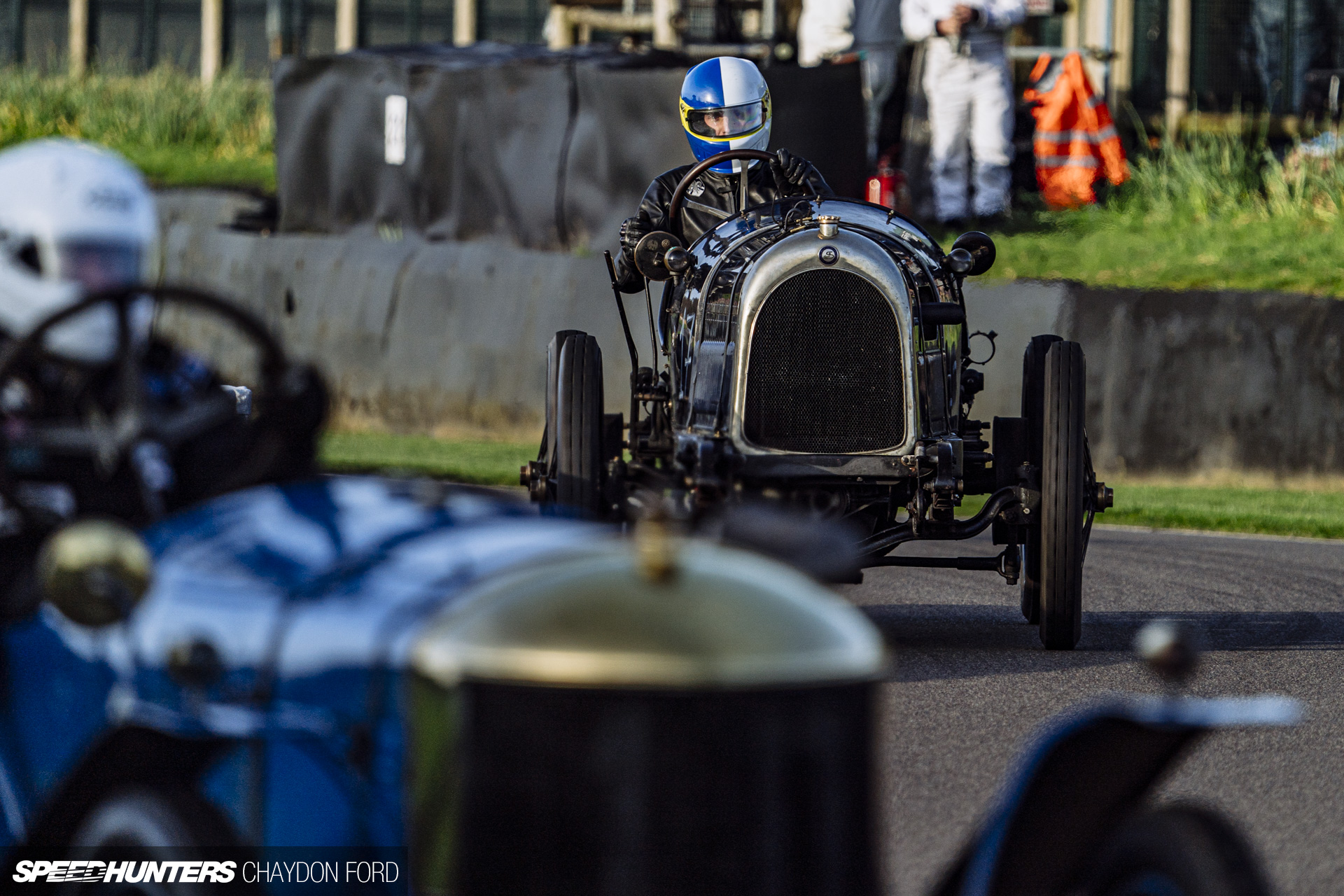

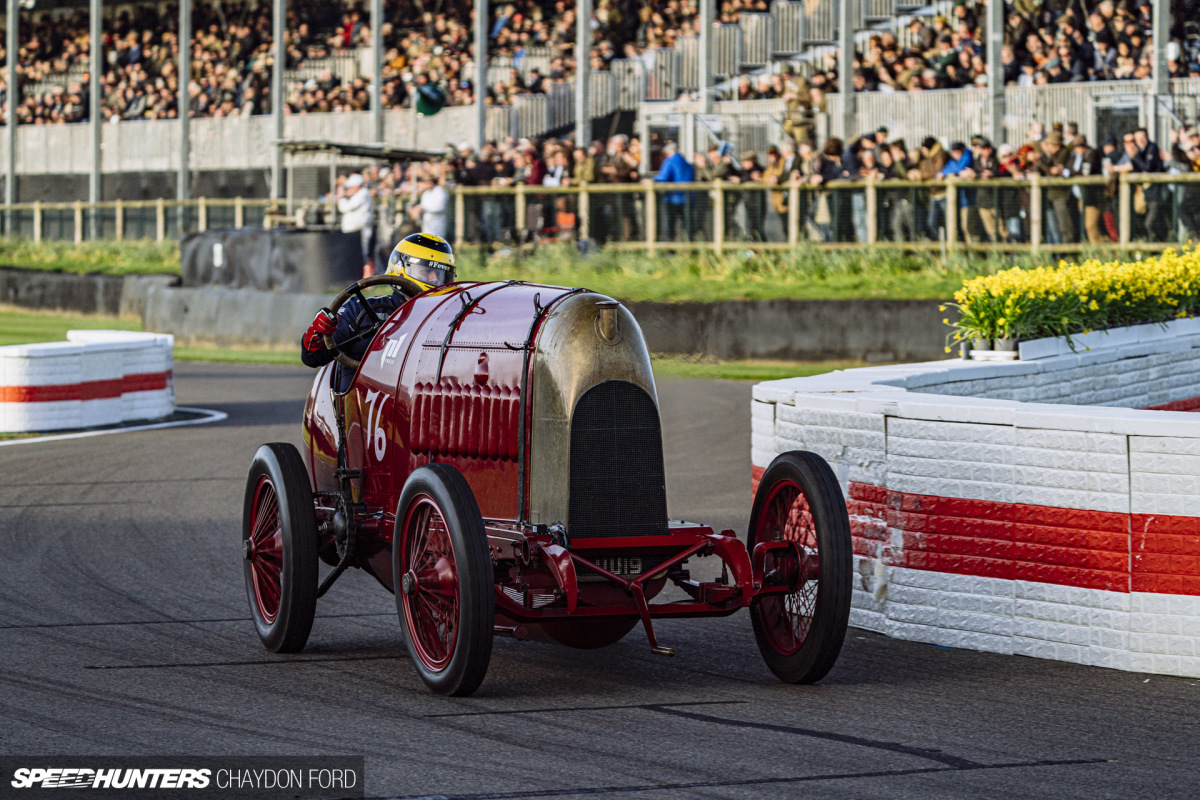

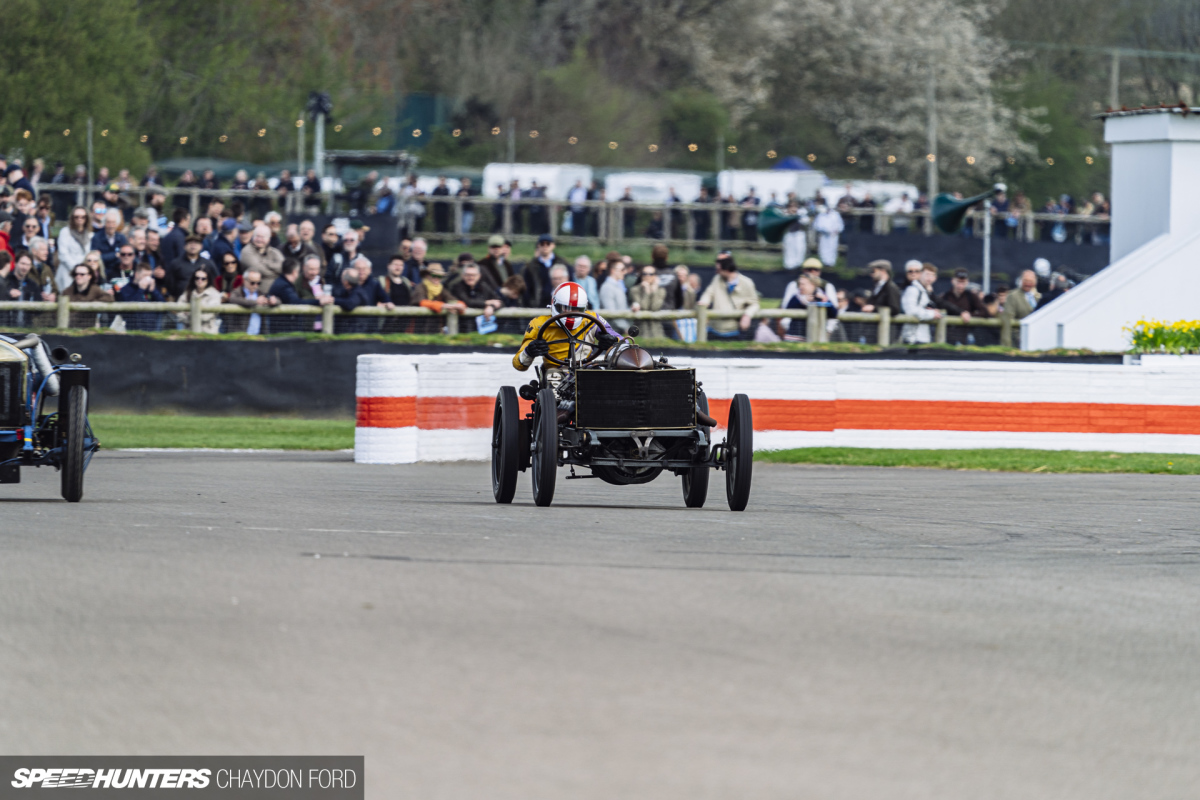

The S.F. Edge Trophy showcased period land speed and Grand Prix cars alongside the aero-engined specials. Watching 20 of these 100-year-old-plus machines battle it out on track and leave nothing on the table was intense.

Now, Edwardian-era racers are very different to what you are used to seeing on Speedhunters are used to, but humour me; these cars were engineered with the same mindset that tuners and builders still embody today.

Vehicle-wise, there were three standouts for me at the recent Members’ Meeting, each unique in their own right with a story to tell.

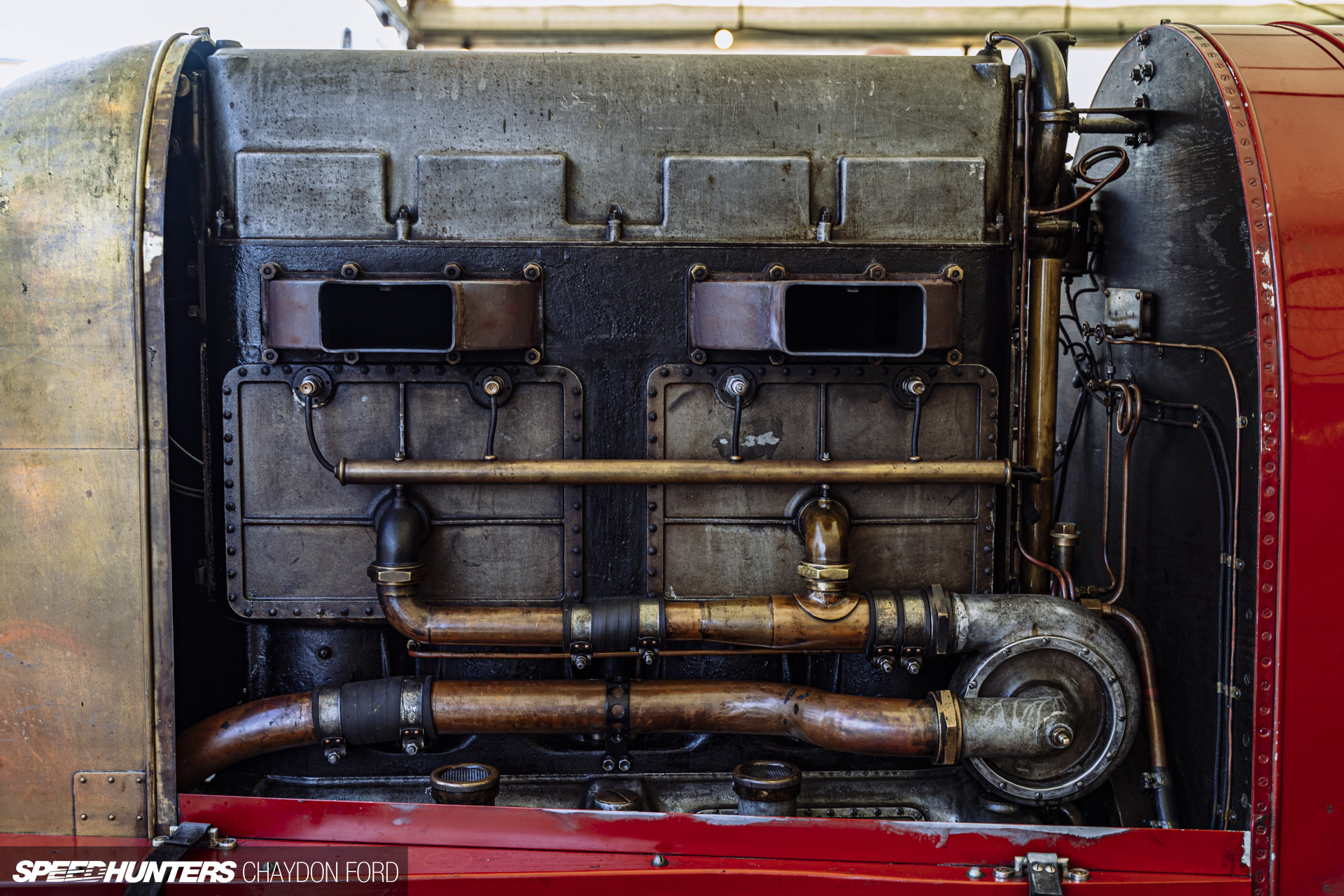

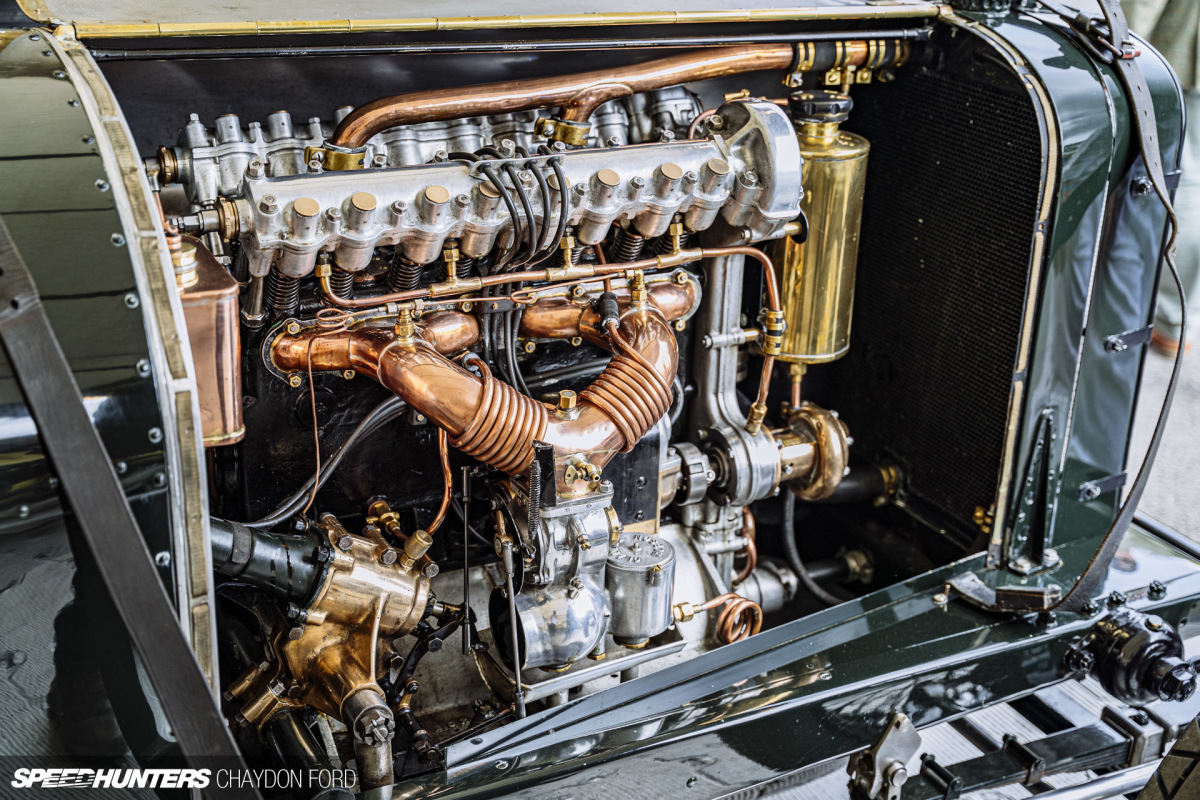

The Fiat S76, more famously known as the ‘Beast Of Turin’, cast an imposing shadow across the paddock. With an engine capacity of 28,343cc (1,739ci) across four gargantuan cylinders, being anywhere in the vicinity you feel every single combustion cycle beat in your chest.

The noise has the ferocity of a shotgun going off, but at 1,000 times a minute.

Word to the wise: Don’t stand too close when the mechanics start it up. Or at any point. You could go deaf or have your clothes set alight by flames erupting from the block with each revolution.

Fiat debuted the S76 in an attempt to beat the land speed record of the time. Two cars were built; Fiat retained #1 while #2 was sold to a Russian prince. The S76 did at one point set an an unofficial top speed record of 132mph, but following World War I the first car was disassembled and the second car ended up in Australia minus its engine. It raced until 1920 with a replacement engine until a crash apparently laid it to rest.

Fast forward nearly 100 years and the second car was brought to the UK. While many parts had disappeared over time, the new owner managed to get these faithfully recreated using original drawings. The car is now a common sight at events and is almost always driven to and from racetracks under its own power.

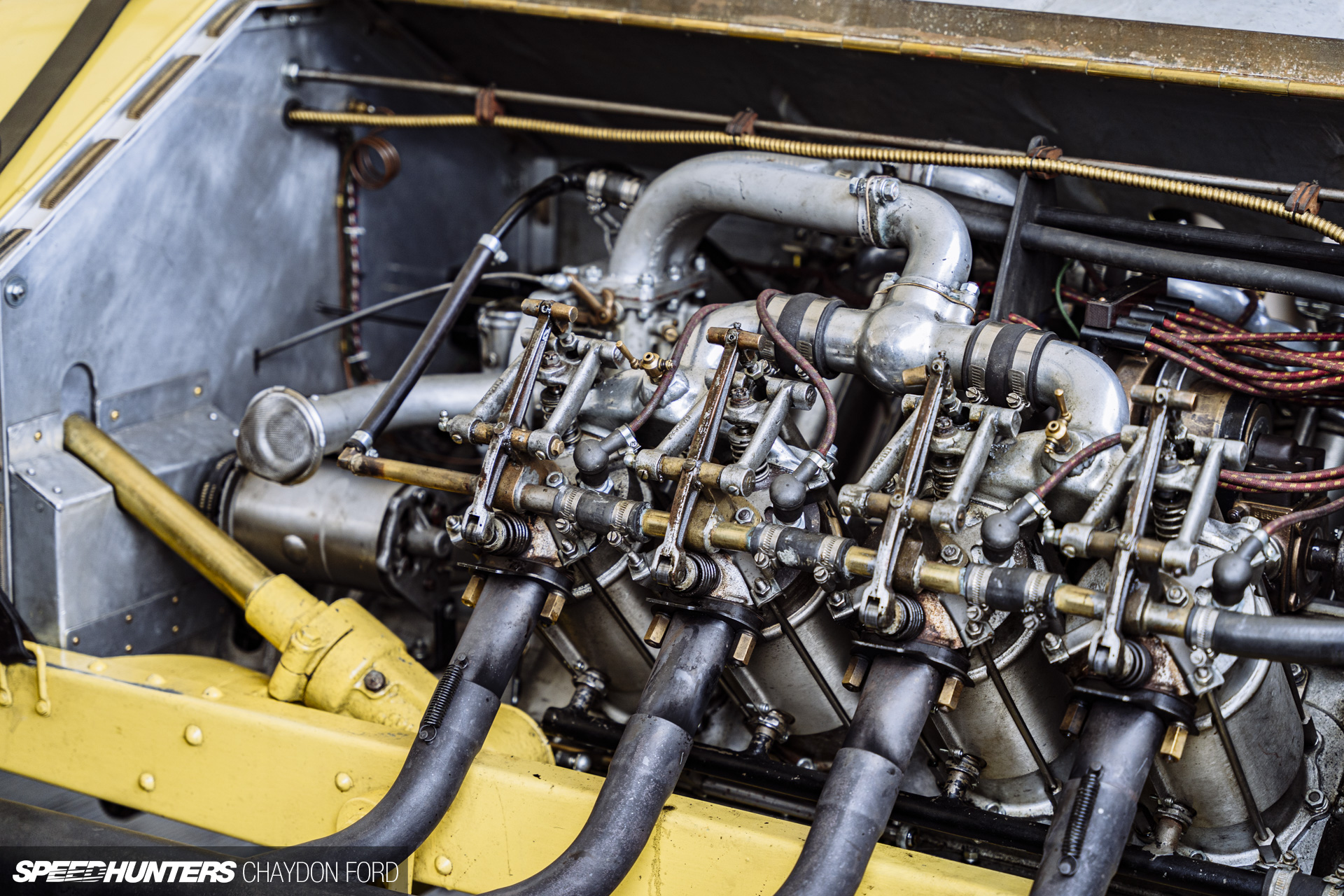

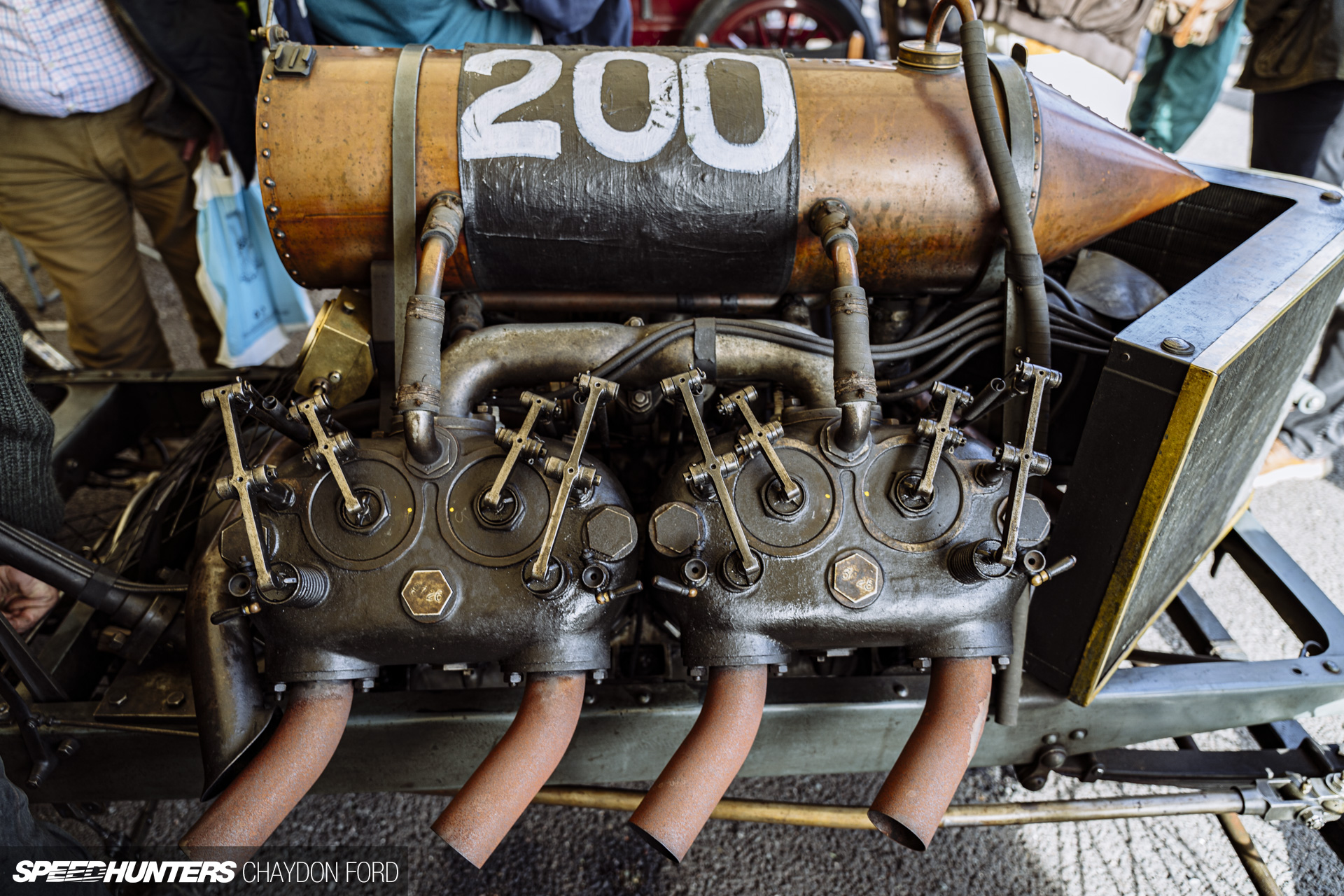

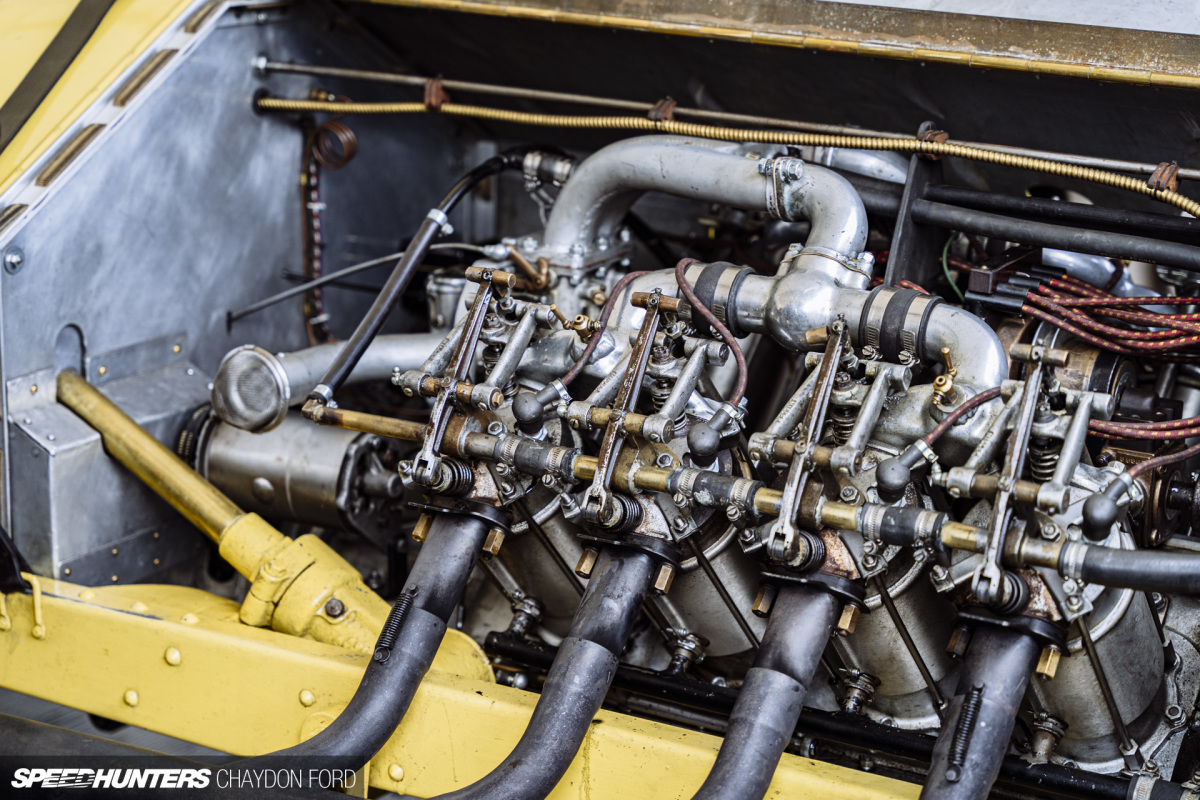

The Darracq 200hp is physically smaller but is no less of a car. It ran one of the first V8 engines ever built, created using a common crankshaft and block and with two inline-four Darracq 100hp engines. The conservative estimate of 200hp came from the 25.4L engine, which when combined with the Darracq’s overall sub-1,000kg weight was enough to propel it to 122mph. It set records and won numerous sprint races in period.

After an engine failure in 1909, the car disappeared from the public eye and was ultimately sent to scrap. Persistent regret meant that a few years later the remains were re-appropriated, devoid of the front and rear axles and only the central section remaining. It sat in this state until sold to the current owner, who over 50 years rebuilt and refreshed what was left. Numerous parts were remade or interpreted from grainy black-and-white photos. The car fired up for the first time in decades, just in time for its 100th birthday.

The unique v-shaped radiator and rocket-shaped water tank make it easy to spot, while the barebones design and big motor combination have meant the car is now often a front runner in historic races.

I was introduced to François, the owner and driver of the third car, by a mutual friend. To attend the Members’ Meeting, François, packed some tools, parts, clothes and his race suit and drove his Theophile Schneider Aero Special 320 miles from his home in Belgium, experiencing all weather conditions along the way.

When asked what it is like to drive such a machine on the road, François explained (with a few more expletives), “Absolutely terrifying, from the moment you sit down, to the moment you park up.”

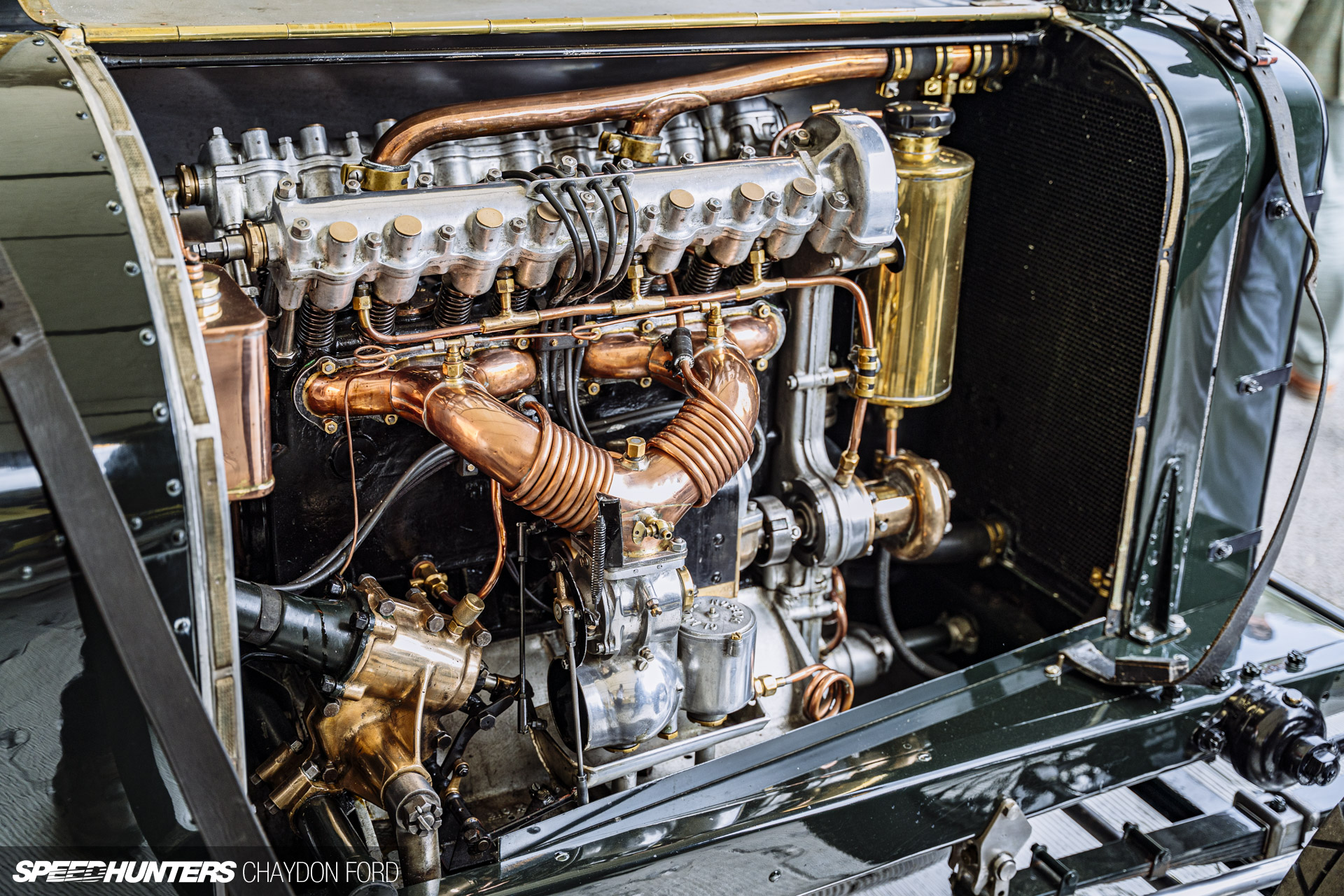

The 10-litre aircraft engine runs through a drop gear to make effective use of the 1,000rpm operating range, but it’s happiest when cruising at 85mph. François went on to say, “Imagine driving an MX-5 on space savers with a welded differential, that you can only slow down with the handbrake. It’s kind of like that.”

Further complicating matters, the clutch started slipping throughout the journey, necessitating its replacement between qualifying and the race. Thankfully, AP Racing makes a triple-plate paddle clutch for the application. Who would have thought?

Topping out at around 100mph by the end of the Lavant Straight, these Edwardian racers may not seem overly fast compared to more modern machinery. But the level of engagement and attention makes up for the lack of outright speed they demand from the driver. Lacking assistance in every single way, drivers walk the thin line between being in and out of control.

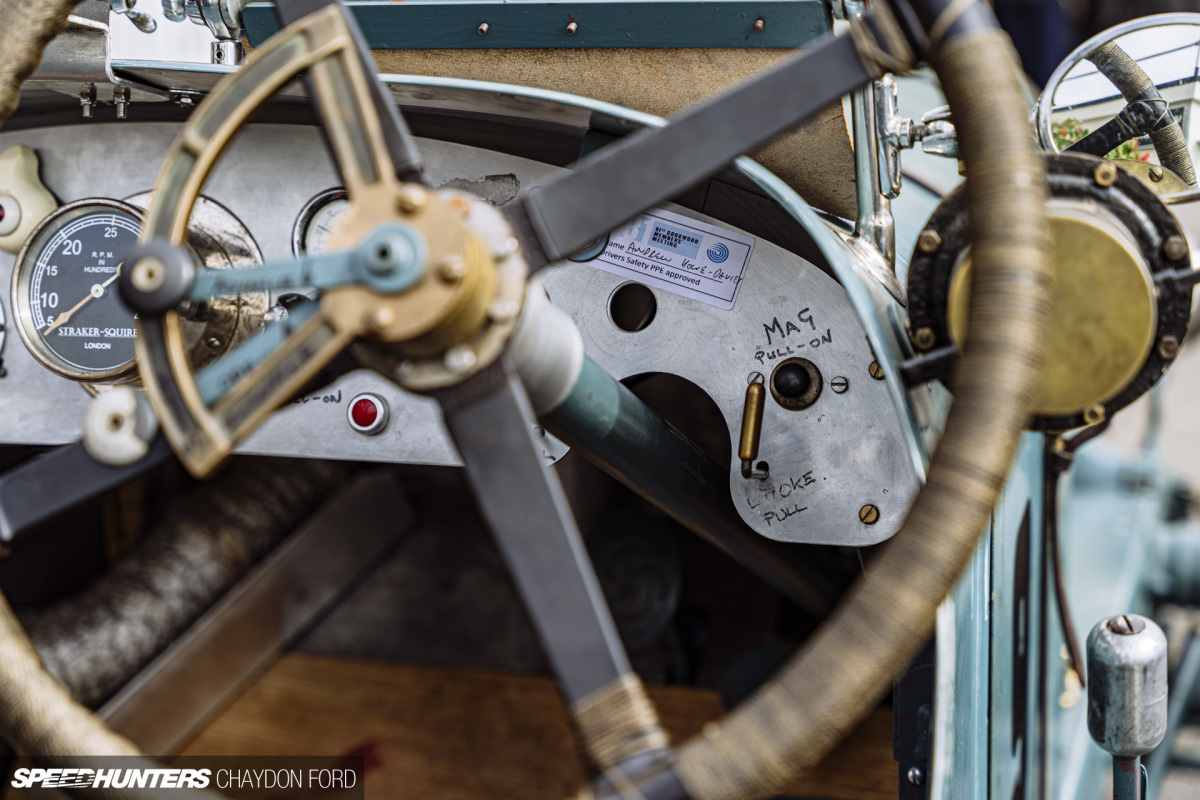

Despite this, it would be a disservice to call these cars rudimentary, as they utilised every bit of automotive technology available at the time. Crossflow overhead cam motors, dual ignitions and open differentials were cutting-edge. But other aspects remind you of their age; wooden panelling, rear-only brakes operated by cable or exposed linkage, and meagre contact patches on their skinny tyres.

Building fuel pressure required the driver to use a manual plunger to pump air into the tank, so it was not uncommon to see this happening while driving at 90mph.

It certainly takes a special person to own and race these behemoths. These are in no way ‘arrive and drive’ specials. Those who choose this type of car are of unique disposition and hugely dedicated. Between races, owners could be found working with oil-soaked hands, evidencing they knew their vehicles intricately and just how simple they were to work on.

With so much electronic technology being packed into modern race cars, long may Edwardian-era racers continue to serve as the ultimate pallet cleanser.

Chaydon Ford

Instagram: chaycore

The Edwardian racing at the members meet is by far some of the most entertaining. Also, looking round some of the cars you realise how early some "modern" ideas really are. This year there was 1914 Sunbeam with twin overhead cams, last yeat there was 1914 Model T based special with an overhead cam conversion and dual spark ignition. That was praticularly neat as it had been in the same family since then with the 3rd generation racing it.

These things are fantastic and it's proper racing, not just a demo run round the track,

Valid point. A lot of ideas now were thought up a long time ago. Mercedes experimented with an air brake in 1955. Now we get a Bugatti where the wing tilts under braking and the kids say WAAAAAAOOOOOW. I don't think the Merc worked in any meaningful way regarding track performance, but the idea was there in the 50s. The driver would open and close the flap manually.

Pretty amazing to look at. I watched the movie Grand Prix, something I’d recommend, it really shows how dangerous and visceral racing was then, no safety equipment, just a helmet.

Thankfully we still have races like the Isle of Man and open wheel european hill climbing series.

These were racing roughly fifty years before that movie was based. Some required a driver and mechanic in the car and were extremely sketchy

Great article, I love these cars!

One question- with the Darracq, what do you mean by a “drop gear”?

it effectively alters the ratio. im not sure what the exact ratio is, but as an example it will alter it so 1 revolution on the input side equates to 2 on the output side

From the era when drivers were fat, and tires were skinny!

Seriously, I'm happy to see these cars being celebrated. The sounds and smells are intoxicating.

Oh yeah- great photos and write-up too.

What a fantastic article and testament to true engineering art. I recall standing in the museum at Brooklands gawking at the aircraft engines with a seat bolted to the back of them which were hurtled around the banked track by women and men who lusted after life between WW1 and WW2. I doubt we will see their like again, however the cars are an excellent memorial to this great generation.

Utter Brilliant - Thankyou

I love this.