Six cylinders, two turbos – a magic quantity of these ingredients that has been applied to so many recipes over the decades. Inline, various Vs; parallel, sequential or series – history is rife with examples past and present.

From Ford to BMW, many sports cars have gone from naturally aspirated sixes up to eights, and now back down to a six or even a four, albeit with forced induction. The benefits of a turbocharger are many, and I’m positive you’re aware of these gains already.

The concept and technology itself is more than 100 years old, but it seems like it’s only since the ‘80s and ‘90s that we’ve really come to terms with mastering the turbocharger with the likes of the Maserati Biturbo and Porsche 959. Sure, turbos were used successfully for decades prior, from farmland to war zones to the racetrack, but the Maserati and Porsche were each the first to use two turbos – one for each bank in the Biturbo and sequentially in the 959, of course – in a production vehicle.

Advancing the technology to a point where it’s viable for production is part of the equation, too, and as with the chip powering the device you’re reading this on now, engineers have always realized that just making things bigger is not necessarily better.

Any physical system involving energy or motion tends to have a ceiling where the laws of the universe become exponentially contrary to your goal. The harder you try, the harder you’re opposed, and this is why two turbochargers are better than one.

But in the real world this adds a lot of complexity and cost, not to mention heat, which brings its own challenges.

But with the advances we’ve made in recent decades, turbochargers can be found in at least a third of light-duty production vehicles today. With the technology not only able to increase power output but also able to decrease fuel input, a turbo tends to make sense in just about any application.

Mastering this technology as we approach a point of diminishing returns becomes ever more incremental, and the same way we have the space program to thank for memory foam and scratch-resistant lenses, we can thank racing programs for advancing and prolonging our love affair with internal combustion.

A turbocharger was first used at the Indy 500 in a Cummins turbodiesel that found itself on pole position for the 1952 race, but it wasn’t until decades later that we saw turbochargers begin to dominate in motorsport.

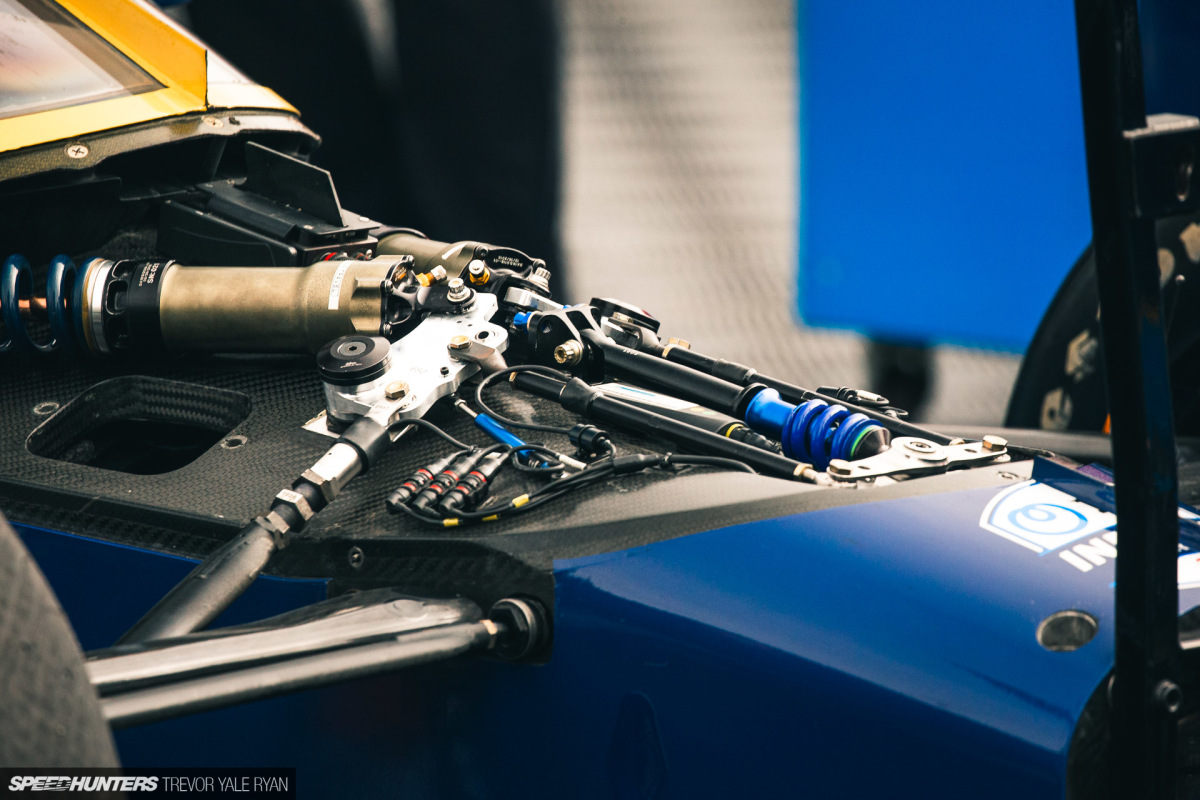

Just over six decades after that Cummins turbo went racing, IndyCar – being intimately aware of the direction the industry was heading – made the rule change for all engine suppliers to use twin BorgWarner turbochargers. This would level the playing field between teams still using a single turbo and would also provide for a more direct real-world application as more and more vehicles move to two turbos. That’s the idea, anyway.

What came about as a result is a 2.2-liter package pushing 700 or so horsepower to the wheels despite various required rules and regulations that are imposed to make the engineers’ lives difficult, including a 12,000rpm redline. Boost limits are also imposed for different track layouts, with a high-boost passing mode at 1.65bar (24.25psi).

The lightweight power plants are placed in a composite monocoque chassis built by Italian firm Dallara Automobili, and the engine is utilized as a stressed member. With a total dry weight around 1,700lb (771kg) for a road course – as opposed to an oval – the results are fairly mind-bending.

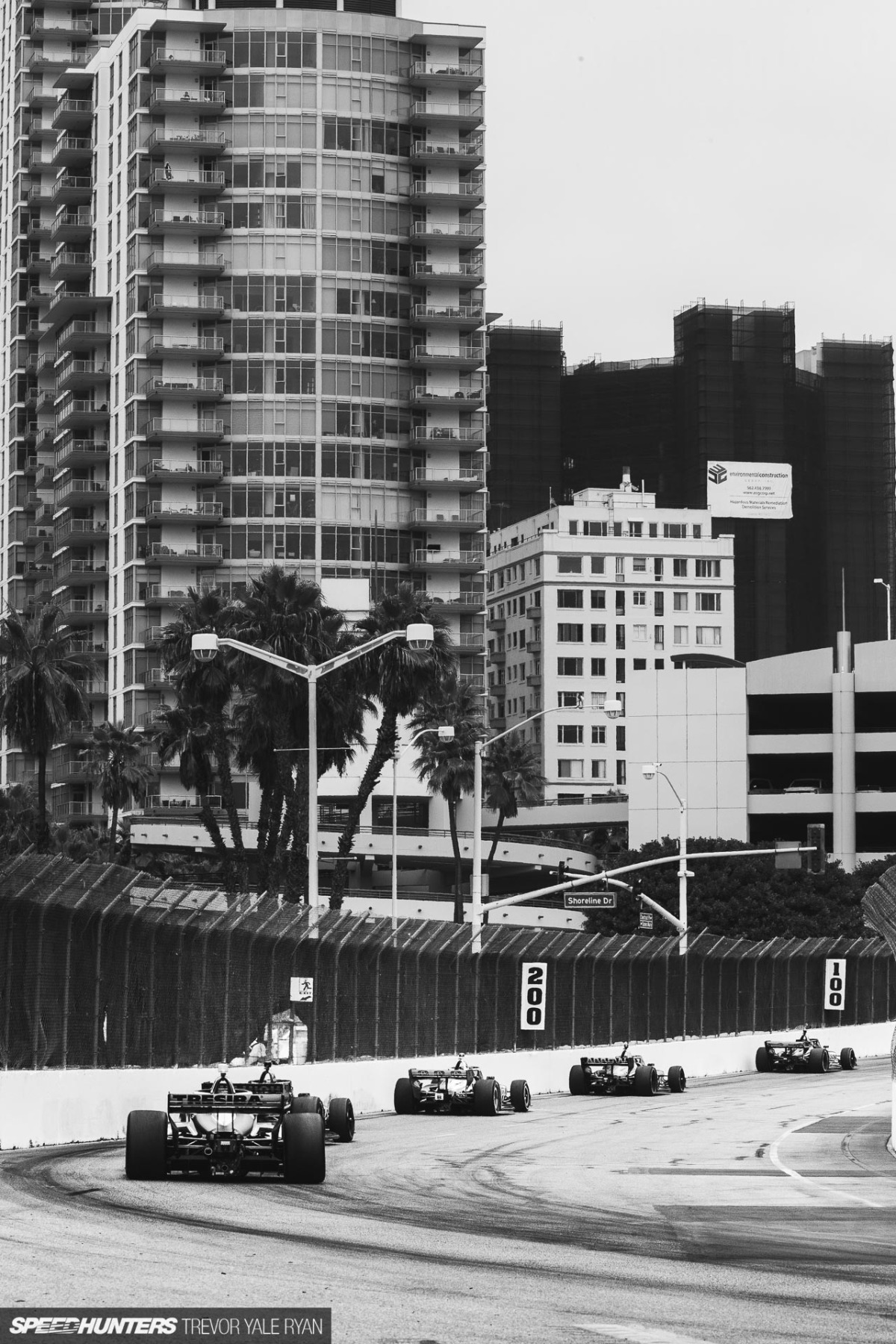

To really appreciate what’s unfolding these cars have to be seen in person, and what better place than at the Long Beach Grand Prix?

Seeing IndyCar race back-to-back with vintage Formula Atlantic on the same track really shows you how far we’ve come in the past half a century. Ignoring the engines themselves for a moment – not to mention wild composite chassis and the thousands of other incremental improvements that have been made over the years – the tire compounds and aero are really what stand out.

In the mid-2010s, IndyCar teams were producing as much as 7,000lbs (3,175kgs) of downforce, or four times the weight of the car itself. Rule changes have reduced that, but we’re still talking insane figures. Couple this with tires that seem to bend the laws of physics, and the difference in speed between IndyCar and production-based race cars isn’t just noticeable, it’s disorienting.

The IndyCar chassis change direction so much more quickly and put the power down in such a way that your mind requires a refractory period when watching one series after the next. IMSA, Formula Atlantic, Global Time Attack, they’re all fast, but stacked up against an open-wheeler there’s just no hope for competition.

After watching IndyCar, the other cars on track look like they’re just forever warming up, until your senses adjust to the different rates of speed and grip.

I can generally shoot most track stuff at more or less the same settings, but my cameras required numerous fine-tune adjustments to keep up with the IndyCar pacing. The race was fantastic fun, with competitors coming inches from me and the barriers at each of the 11 apexes around the Long Beach street course. So, although I was probably more interested in watching the GT cars go ‘round, the spectacle of an open-wheeler never fails to impress.

Having one foot in that camp myself, though, I fully understand why some go so far as to say Formula 1 and IndyCar are too boring to watch in comparison with their production car-modeled counterparts; i.e. series with Ferraris, Porsches, Aston Martins, Fords and what have you.

As the margins for performance become more slim, the good line through the track seems to narrow. This leads to less passing and, thus, less excitement. The cars don’t look or even sound like anything we’re used to driving, and we can only dream of the g-forces they’re experiencing. Open-wheel cars just aren’t relatable on the surface.

However, these top shelf single-seaters push the envelope and help to provide the essential building blocks of innovation so that we can enjoy racing more at all levels. When watching this race through that lens, the feats that only these vehicles can perform become all the more impressive and important.

As these advancements trickle down, commoners like you and I get to enjoy them on the road each day. With perhaps the slightest of shifts occurring with a few brands reviving once-dead sports cars, let’s hope performance and engagement in the experience continues to be a driving factor in their design. If it isn’t, as drivers we’re doomed to a future of vague road feel and mushy cars that simply get you from one place to the next.

Speaking of drivers, Colton Herta took first place from 10th on the grid for Andretti Autosport, his second consecutive race win and third of the season.

The race weekend was also the season finale for IndyCar, which saw their first Spanish Champion in 24-year-old Alex Palou of Chip Ganassi Racing.

Trevor Ryan

Instagram: trevornotryan

tyrphoto.com

"As the margins for performance become more slim, the good line through the track seems to narrow. This leads to less passing and, thus, less excitement. The cars don’t look or even sound like anything we’re used to driving, and we can only dream of the g-forces they’re experiencing. Open-wheel cars just aren’t relatable on the surface."

couldn't have said it better myself, I'll watch priuses go around laguna seca before an indy or f1 race, just my two cents.

What makes open wheel racing thrilling is the risk factor. They are far less forgiving than any sports car racing and the smallest of mistakes will end your race early. I've watched indycar on road courses and at Indy multiple times and nothing really compares to the actual 500. There is actually quite a bit of passing on the ovals if that's what you like. It's just unfortunate that the windshield looks so awkward, hopefully they find something more aesthetically pleasing in the future.

Dude the black and white portrait shot of the back of the cars is awesome, almost like the 70s with the street circuit, apartments and palm trees. Such a vibe.

Great feature. Always impressed with your photography. Oddly enough I was having a conversation with a hall of fame open wheel driver and he stated they are actually very easy to drive on ovals these days. This is someone who competed in the venturi underbody era of open wheel racing and made the comment that 1,700lbs is actually quite heavy for an open wheel car.

While unrelatable to most people I don't think that takes away from the impressive nature of the machine. More people should be into open wheel racing cars as they make things like drifting etc seem pretty dull afterwards. Different levels to driving like all things in life though. Keep this kind of content coming please!

This is a beautifully written piece! Love it!

Great piece; beautiful photography (both track action & podium shots) and insightful commentary. Well done.