Those of a nervous disposition needn’t worry, this is not the frightening tale of a British sports car manufacturer.

There won’t be all the horror tropes that come with the tale of a low-volume fibreglass car builder. You know the clichés I mean. There’s the one where the company starts making kit cars but then gets desperately close to bankruptcy, there’s the bit where the manufacturer sees huge sales successes until a financial cirrus almost causes insolvency, and also the one where a new owner with no realistic understanding of finances allows their hugely ambitious plans to cause the company to go bust.

No, this story is about the competition side of Lotus, later known as Team Lotus. And although there are sad moments – as is the way when racing in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s is integral to a tale – there’s also world-beating engineering, masses of title wins and a lot of trophies.

Yet this all-conquering race team started in a very humble manner, in the lockup of Hazel Williams’ parent’s house in the late 1940s. Her boyfriend and later husband, Colin Chapman occupied the space to modify Austin Sevens, which he would use to compete in trials, then hillclimbs and sprints before they were adapted for circuit racing. Chapman’s alterations were so effective that his cars gained a degree of notoriety, so much so he thought it was wise to give them a title: Lotus.

These formative years became the bedrock for the company and, even though we’re not talking about high-level Formula 1 competition at this point, just club racing, Chapman gained a reputation for being able to extract speed from machines. By 1953 Chapman had broken away from the little Austin and started building a vehicle of his own design, the Lotus Six.

It was around about this time that Lotus Cars, or Lotus Engineering as it was known back then, was split from the competition department. Although both were headed by Chapman, the racing efforts would go under the name of Team Lotus starting with the Mk VIII, IX and X – a range of 1,100cc and 1,500cc sports cars.

A 1,100cc Coventry Climax-powered Mk IX was the first Lotus to compete at Le Mans in 1955. Chapman himself was one of the drivers, but was later disqualified for reversing back onto the circuit after coming off at Arnage. This annoyed Chapman, but rather than get the hump with the ACO, the French body that organises Le Mans, he vowed to go back and truly make his mark on the race.

After some very careful planning, he got his own back. In 1957, in their infinite wisdom, the ACO made the prize for winning of the Index of Performance, a special award that took into account engine capacity, to be the same amount of money as the overall win. Why? Because the ACO were convinced the French DB Panhards would win the Index. Chapman only had the ‘Index of Performance’ title in his sights and had a special 750cc Coventry Climax engine built for the Lotus Eleven. With Cliff Allison and Keith Hall at the wheel, the Eleven took the coveted title, denying the French team the win and the big prize money. Not at all what the ACO had planned.

Chapman might have had Le Mans and sports cars niggling away in the back of his mind, but at the forefront of that big brain of his were single-seaters and Formula 1. He’d been commissioned, along with Frank Costin (aerodynamicist and brother of Lotus employee and Cosworth founder, Mike Costin) to design Vanwall’s 1956 Formula 1 car. It proved to be a huge success, winning in England and Italy in its first year, then taking the flag at eight Grand Prix and the constructor’s title in 1958.

Vanwall almost turned Chapman into an F1 driver, too. He was considered a very talented racer by his peers and was given the opportunity to drive the Formula 1 car he’d helped design in the French Grand Prix at Reims. During practice the rear brakes locked, he lost the car and crashed while at the same time losing his chance to start the race.

In 1957 Lotus built its own single-seater, the 1,475cc Coventry Climax-powered front-engined Type 12. Although initially designed as an F2 racer, it was adapted to compete in F1 at the start of 1958. It was an advanced car and it debuted Lotus’s strong and lightweight ‘wobbly web’ wheels (cast magnesium wheels without holes or slots, but spokes made from ripples) and the simple Chapman strut rear suspension (essentially a MacPherson strut but without the need for the wheels to steer). Sadly, in both Formula 2 and 1, it wasn’t very competitive. It’s successor, the Type 16, only improved the team’s standings slightly, but its front-engined layout still wasn’t a match for the mid-engined Cooper.

The Type 16 was also unreliable. Works drivers of the time noted that Chapman’s attitude to race car engineering was to make components as light as possible. If they turned out to be too weak and broke, only then would you reinforce them and make them heavier. A scary proposition when racing crashes of the time frequently ended in serious injury or death, and this attitude really adds a different dimension to Chapman’s famous ‘simplify, then add lightness’ philosophy.

Yet, Lotus wouldn’t have been a success if it had only created flimsy cars. The successful innovations Chapman developed far outweighed all those dubious and liable to break mistakes. And once Chapman had admitted that the Cooper’s mid-engined design was superior, new and groundbreaking concepts began to flood out of the Team Lotus factory doors.

The first mid-engined Lotus F1 car, the 1960 Type 18, was also the first Lotus to win a Grand Prix. The year after, in the super-slim Type 21, where the car’s frontal area was so small the driver had to almost lie down, Innes Ireland succeeded for Team Lotus and took the chequered flag.

In 1962 Jim Clark was brought on board as a works driver and the success came rolling in at a rapid rate; in his first year he almost bought Lotus its first championship win. The year after, in the Type 25, Lotus and Clark absolutely shined. The new car’s monocoque structure made the rest of the field look antiquated by comparison and Lotus became the team everyone copied. In 1965 Clark not only took the F1 world championship but also won The Indianapolis 500 in a Lotus.

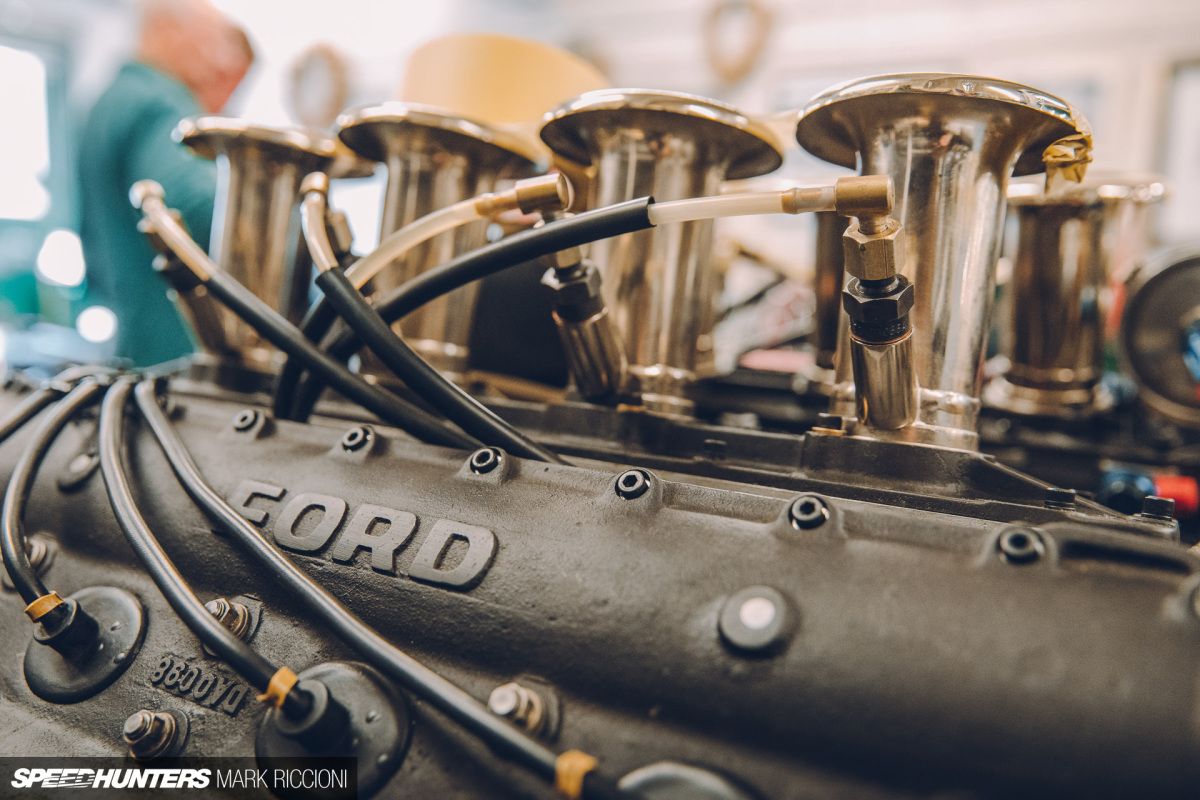

The next big leap in F1, again made by Lotus, was as much a business innovation as it was to do with engineering. Chapman persuaded Ford to fund Cosworth’s development of a new racing engine. The result was the DFV, a three-litre, four-valves-per-cylinder 90-degree V8 that went onto power almost every car on the F1 grid at one point. Initially, however, only Lotus could use the new V8 and rather than popping it in one of its monocoque structures, the engine and gearbox actually formed the rear half of the Type 49’s chassis. Or as a stressed member, as it’s known if you’re not too squeamish.

Chapman’s business acumen remained in full force alongside his engineering prowess and he took advantage of the new sponsorship rules within F1. In 1968 Lotus became the first works team to change its cars’ entire liveries to match the colour of their sponsor. The Type 49 changed from the traditional green and yellow of previous Lotus race cars to red, white and gold; the packaging colours of Gold Leaf cigarettes.

It’s with the DFV-powered Type 49 that Lotus began experimenting with downforce, adding wings to the front and back of the car to push it onto the road at speed. The rear wing started high over the back axle, so it could cut through the clean undisturbed air above the car. Unsurprisingly, the spindly props were prone to failure and, in the middle of first practice for the 1969 Monaco Grand Prix, high wings were outlawed completely. Rather than running the main race wingless, as they had in qualifying, Lotus fashioned an ad hoc spoiler from a sheet of metal allowing Graham Hill to take the victory on the Riviera street circuit.

The culmination of what Chapman and Lotus had learned with its aero development, as well as its trackside experiments, all went into the Lotus Type 72. This new F1 car debuted in 1970 and raced for six whole seasons, securing 20 Grand Prix wins, two driver’s titles (one for Jochen Rindt, which he won posthumously after dying in a crash during qualifying at Monza, and one for Emerson Fittipaldi) as well as three constructor’s championships for the team. It was also the first car to wear the iconic John Player Special livery that 1970s Lotus F1 cars were famous for.

Team Lotus repeated the trick later on in the 1970s with the Type 79, and it proved to be just as dominant as the 72. Chapman had taken downforce to the next level: ground effect. By carefully channelling air under the car and managing the high and low-pressure areas with side skirts and venturi, the 79’s aero didn’t generate the same drag as its predecessor. Or, more importantly, as much drag as its rivals. In 1978 Mario Andretti won the driver’s title and Lotus took home the constructor’s gong.

However, this was the last time Team Lotus would take either of those titles and race wins would become less frequent into the 1980s. Lotus was almost a casualty of its own success. Or, at least, its own creativity. The twin-chassis Type 88 pushed the rulebook too far, and the organisers banned it. Then, in 1982, after witnessing Elio de Angelis take his first win in a Lotus Type 91 earlier in the year, Chapman died of a heart attack.

Although distraught, Team Lotus continued without Chapman and continued to pioneer new technology, like computer-controlled active suspension. They also continued to win, just not in quite the same commanding way that they had in the 1970s. Although de Angelis and his teammate Nigel Mansell tried their hardest, it wasn’t until Ayrton Senna joined Lotus that the team would see another podium top spot. Lotus’s last win came in 1987 in Detroit at the hands of the young Brazilian driver.

At the start of Lotus’s Formula 1 success in the mid-1960s, Chapman took over an old RAF airbase in Norfolk. This site on Potash Lane in Hethel had two runways and a set of perimeter roads that could be adapted into a test track. There were also buildings and hangers that could be used as offices, factories to construct road cars and a place the F1 team could call home. So perfect was the airbase, that Lotus has been situated at Hethel ever since.

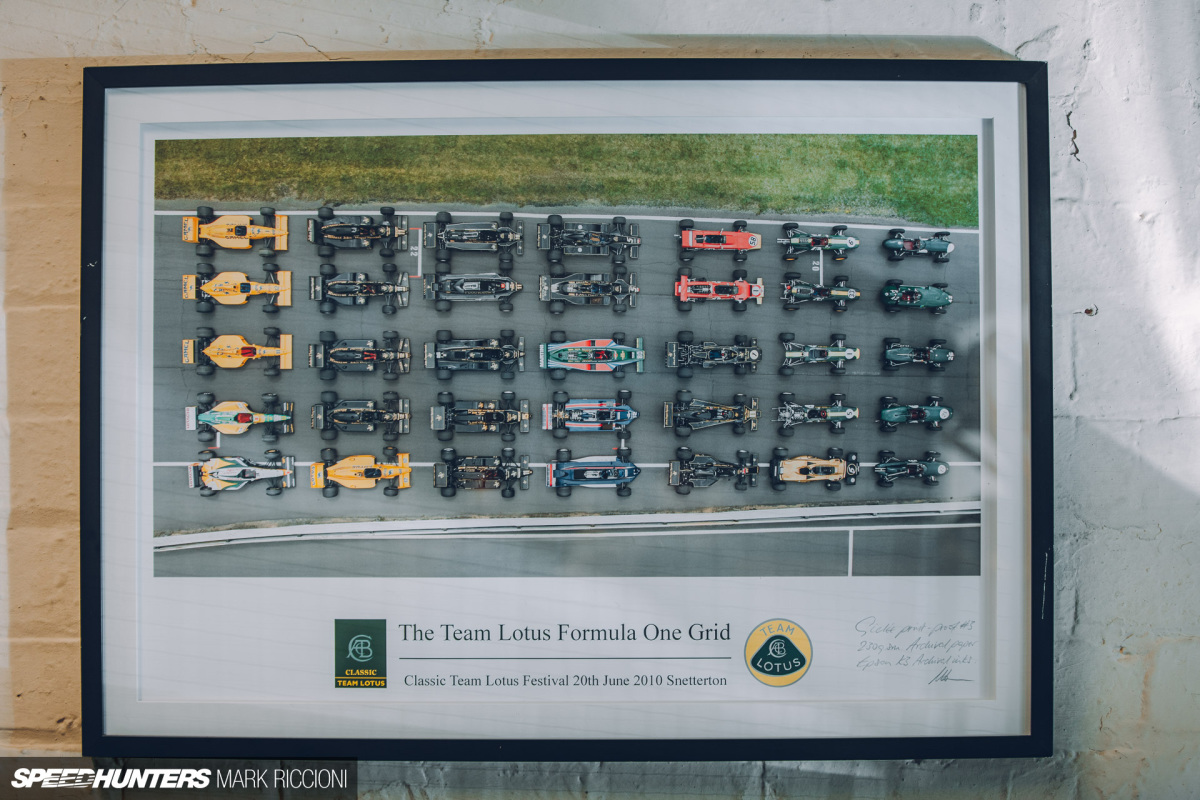

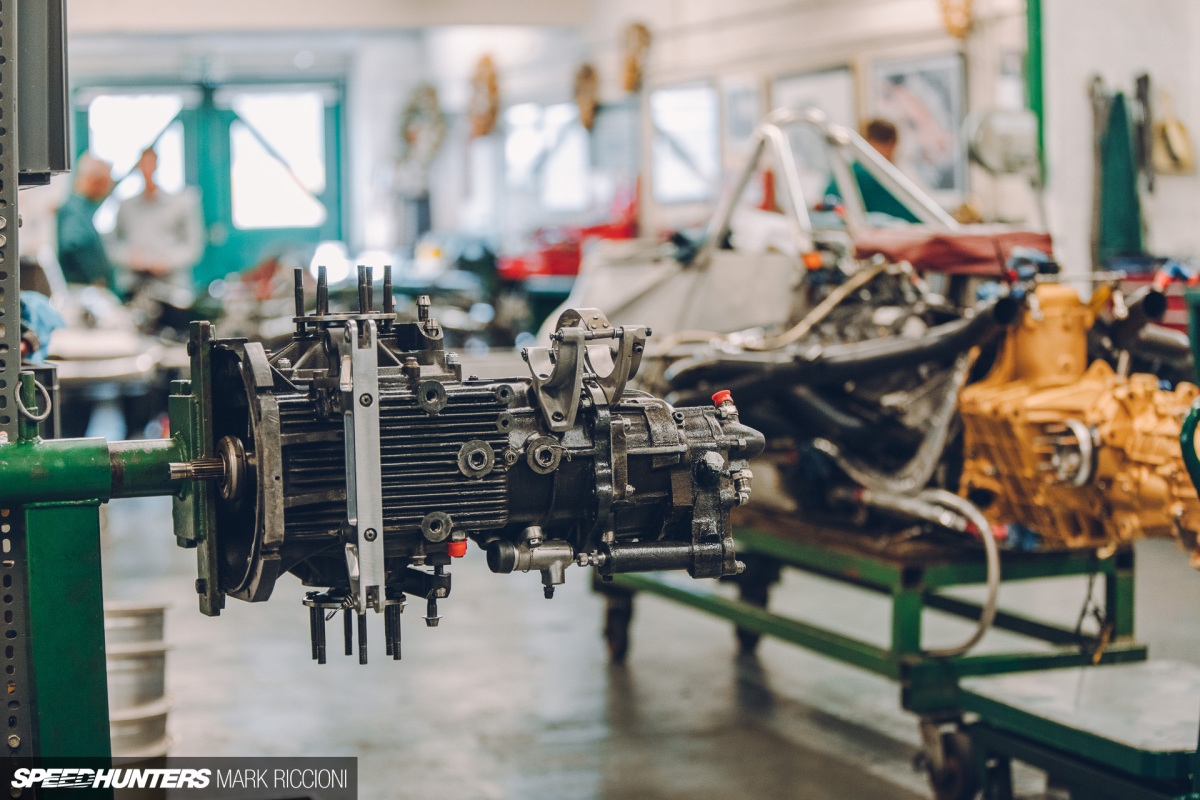

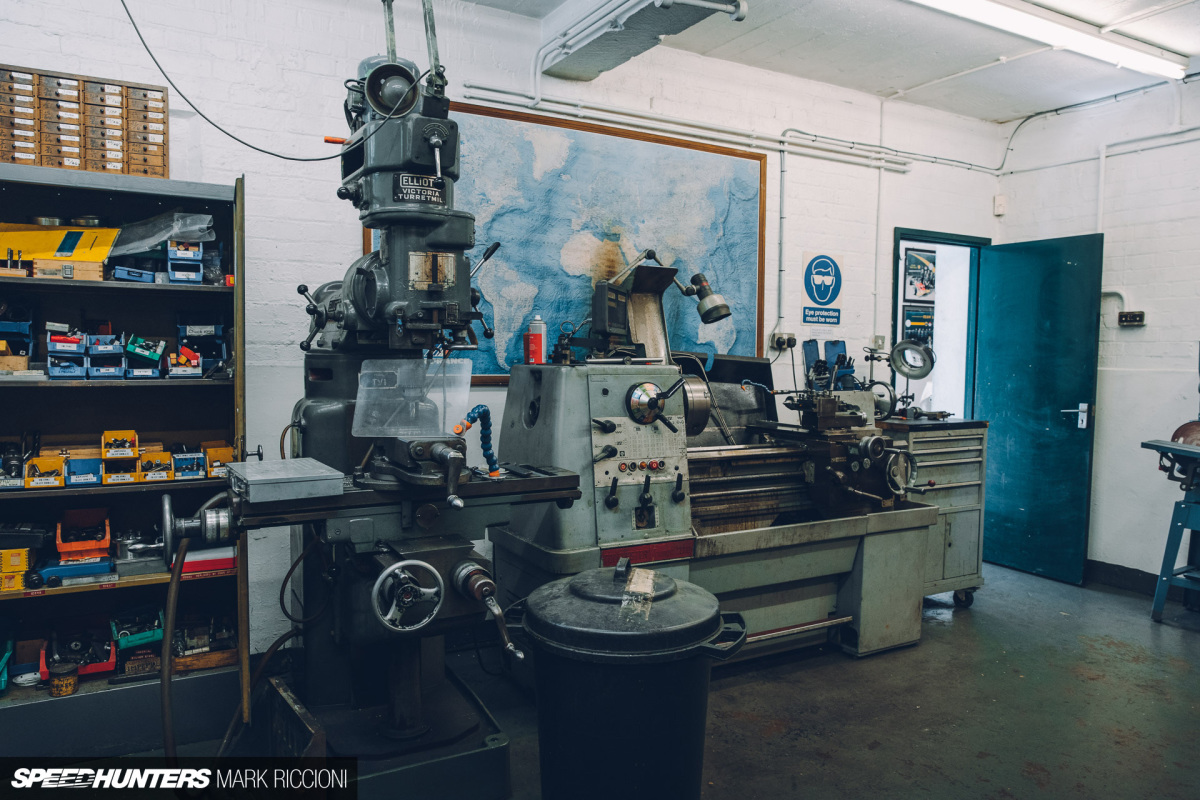

Although Lotus are no longer involved in Formula type motorsport, Hethel’s test track occasionally still reverberates to the sound of Coventry Climax engines and DFVs thanks to Classic Team Lotus. Run by Clive Chapman, Colin’s son, Classic Team Lotus cares for its own collection of cars and supports owners who race old Lotus competition cars in historic motorsport. And, until recently, the team was based in exactly the same building as where all the post-65 Formula 1 cars were originally built, too. But, what with historic racing becoming increasingly popular and having dozens of cars to look after and restore, Classic Team Lotus simply outgrew these buildings.

Its new facility is much bigger, allowing the cars to live out on display and the new workshops are so exceptionally high-tech and swanky that it’s an absolute pleasure to spend time just looking around them. Honestly, they’re so clean that, if I needed a sterile environment for someone to perform brain surgery on me, I wouldn’t choose a hospital. I’d want them to cut me open on the floor of the workshop.

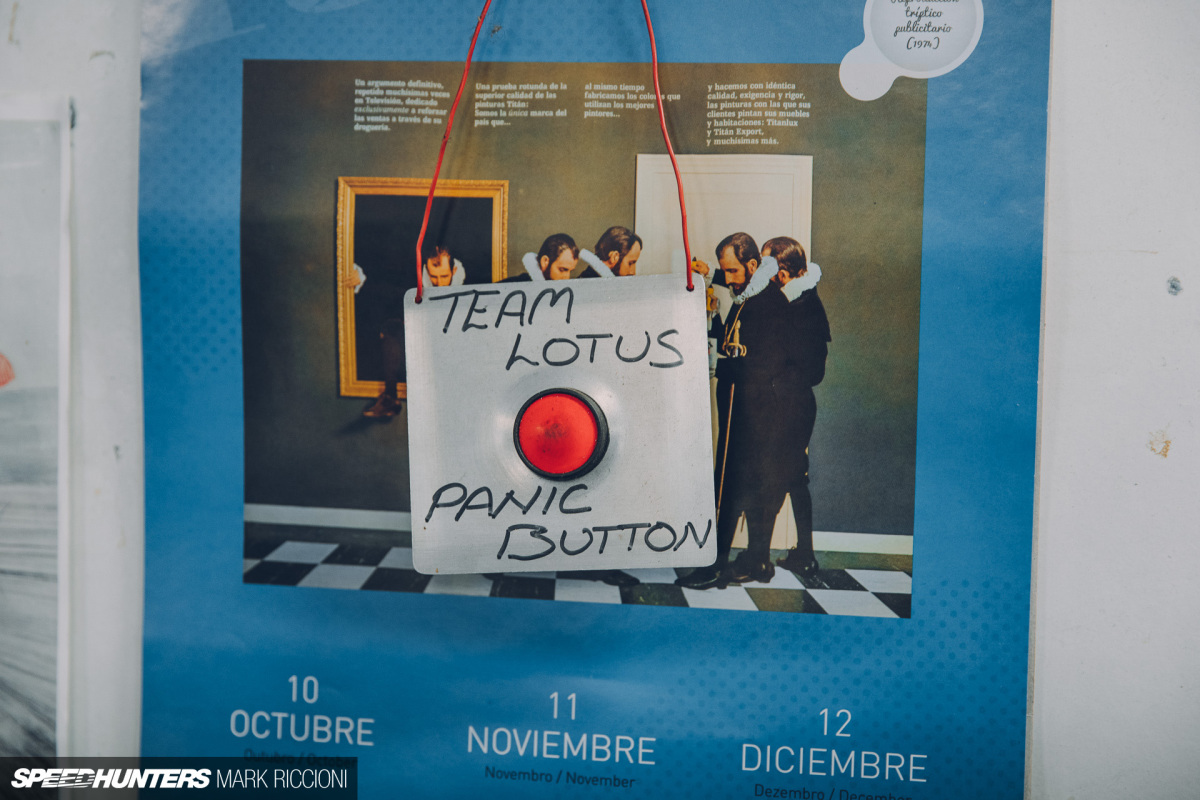

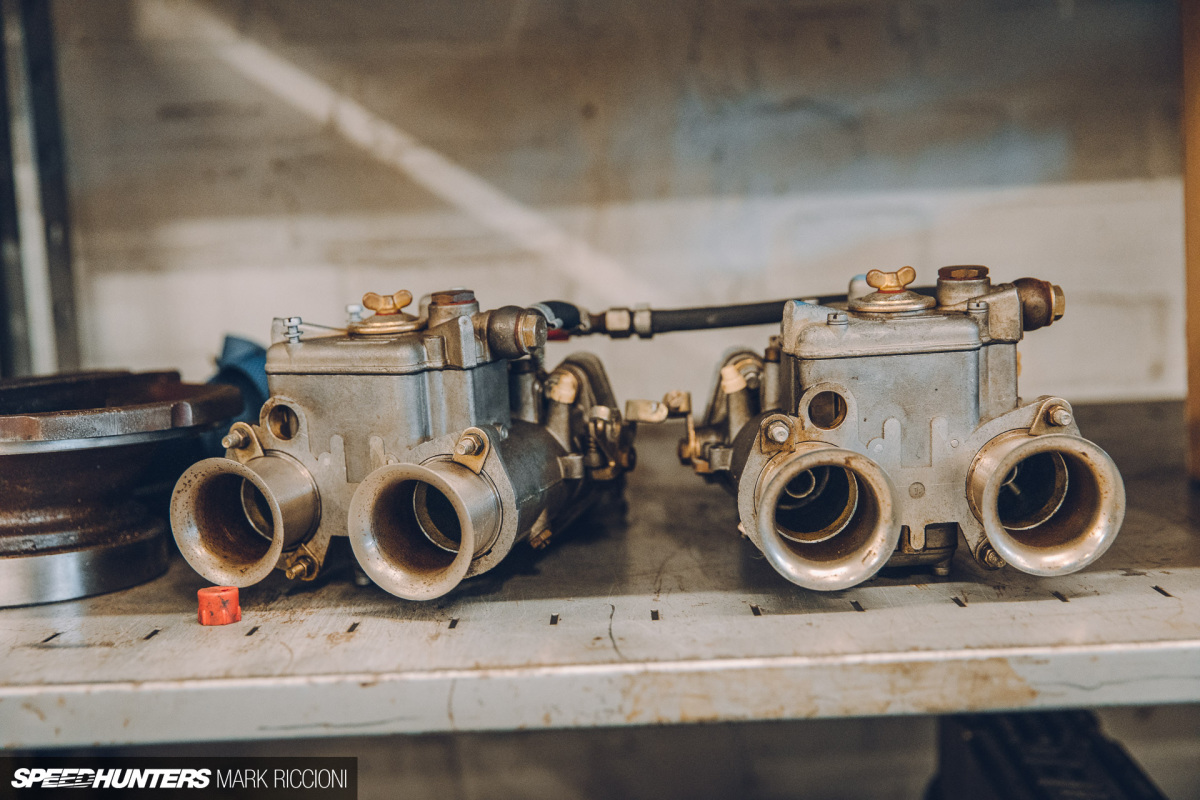

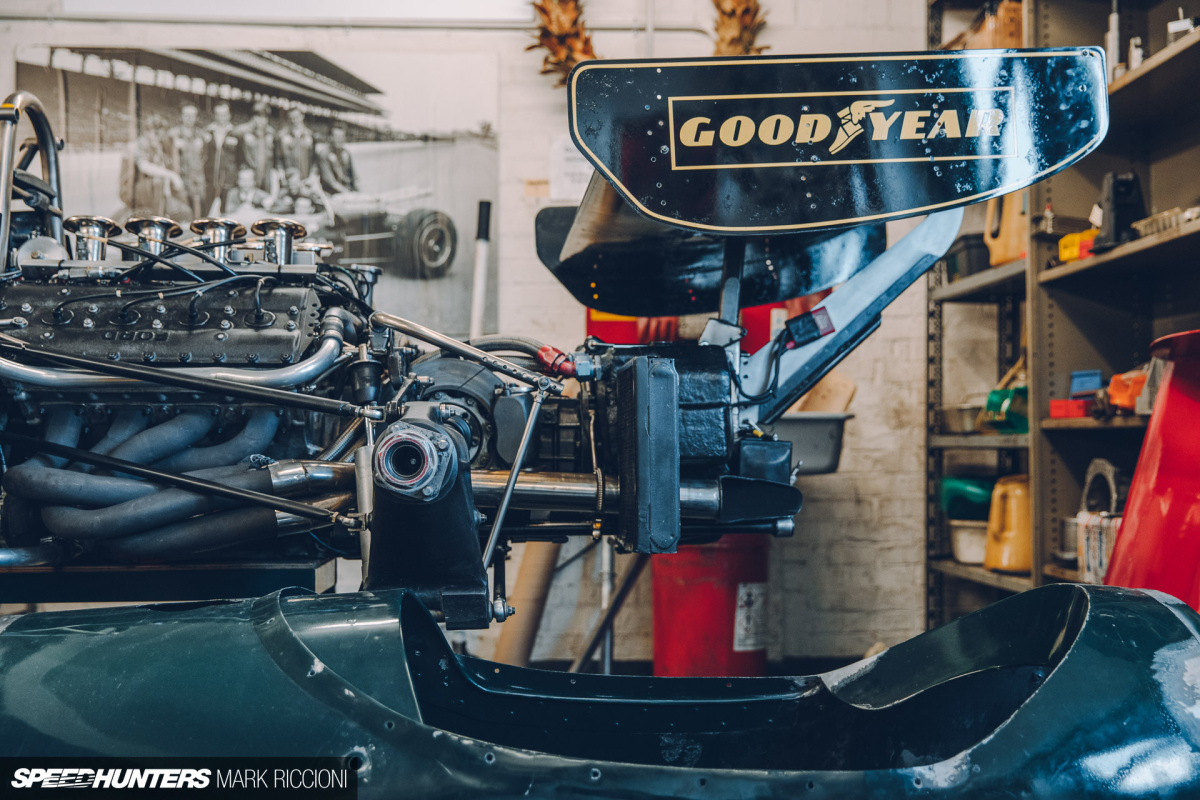

There’s no doubt why Classic Team Lotus needed to move. Every part of the place was full; the walls plastered in posters and photos, the shelves creaking under trophies and bottles of champagne and boxes overflowing with once high-tech bits of magnesium. It was as much as storage warehouse as it was a workshop.

More than actual stuff, Team Lotus’s old workshops were brimming with memories and charm. Sadly, sentimentality isn’t enough of a reason to stay in an unsuitable location, but that doesn’t mean we can’t reminisce with these photos of the fascinating, loveable and historic original buildings.

Will Beaumont

Instagram: will_beaumont88

Photography by Mark Riccioni

Instagram: mark_scenemedia

Twitter: markriccioni

mark@scene-media.com

No JDM, no overfenders, not 1000hp - no comments?

The "old" guys won't complain and the likes seekers not interested / didn't understand what's going on. This article is more like reading a magazine than a keyboard warriors battleground.

Pictures are good, childish weakling narrating it not so much.

Would be cool to see Lotus return to F1

Hmm... Lotus cars. Loved them. but then there's this question going around.. and it'll go around for eternity. Colin Chapman. Genius or Murderer? A lot of very talented people died in his cars, and justifying that by saying he won trophies seems rather weak. Yes, that was the times, I know. I lived it. But I can't bring myself to agree with his philosophy of only strengthening a part after it breaks. How do you sleep at night knowing that someone died because you made a part too light, too thin? My personal thoughts are that genius would work out a way to win and also keep the driver alive.

I'm pretty sure they weren't building parts they thought would break and cost them a race. For somebody that "lived it", you don't seem to understand the engineering from that time period

Then I would suggest you rethink your "sureness". They would then, and still do now, risk putting on parts that may fail in order to beat the other team and win. You've never seen an engine blow? or tires fail? or suspension break?

We could say the same about Ferrari back then, don't we?

I'd blame the FIA more for having practically nothing in the way of safety back then. Colin was just someone working within those rules. Today all those parts have minimum strength/reliability requirements to be considered safe for racing.

Even then, Rindt's letter to Chapman comes to mind when you wonder if he was pushing it a bit too far.

Yes, exactly my point. Rindt's letter. They all knew the limits were being pushed to the extremes. The FIA was mentioned in one reply, but they didn't really exist then. The push for safety came from the drivers, and change only happened when they boycotted races. Even then, the changes were unwilling. Another reply suggests I dont understand engineering. Oh well, throw my degree out then, that was a waste of time... Hahah! It had nothing to do with engineering, it had everything to do with pushing the limits too far. They knew the risks they were taking. Rindt certainly did. I'm quite certain Chapman also did. Unfortunately I think we need to simply put this down to how society framed risk in those days. These days we are certainly more risk averse, and the rules don't allow people to push the limits so far that life is at risk, let alone a race.

Not that I'm defending but this implies to a lot others (1st in mind Lancia), but as you've already stated that was the era when craziness was brilliance (from manufacturing side) and big balls (from drivers side). We need to find that sweet spot were the regulations are not boring to death and the safety is good enough.

What colour is that audi tt?

Lotus returning to F1 would be great.Crowds would go insane as well. I havent actually thought about Lotus preserving their old racing models though,interesting....

You'd think so. but I don't think they would. The genuine 2010 team was a disaster despite having Trulli and Kovalainen at the wheel (Very little support from what I remember too), and the Renault "Lotus" team didn't fair much better in the long run ending up bankrupt after just a few years. They did get a few wins though and podiums whilst having Kimi Raikkonen and Grojean.

Absolutely incredible. Great feature Mark!

Racing cars running on bias-ply tires always gives me goose bumps.

Thank you for the inspiration! Such a perfect workshop <3