Sometimes you do not need the Ouija board to forecast the outcome of an event. Ten years ago it was the assembled wisdom that Audi would dominate the Le Mans 24 Hours and finish 1-2-3. So it came to pass. Mind you, the same, self appointed experts reached a similar conclusion about Peugeot this year and we all know how that turned out. That, perhaps, encapsulates the enigma of Les Vingt Quatre Heures du Mans.

The image above shows the staged finish; the flag waving and enthusiasm of Emanuele Pirro in #8 Audi indicates which of the R8 trio has won. This was to become a recurring dream for Audi over the following decade and a corresponding nightmare for their opponents.

Of course what was not obvious to most of us, although it should have been, was how far ahead of the opposition Audi were. They had applied real intelligence and savvy to the issues encountered by their entries in the 1999 race. Both the R8R and R8C cars had suffered with transmission problems, losing huge amounts of time. The solution not only build a better system but construct it in a way that made repairs easy.

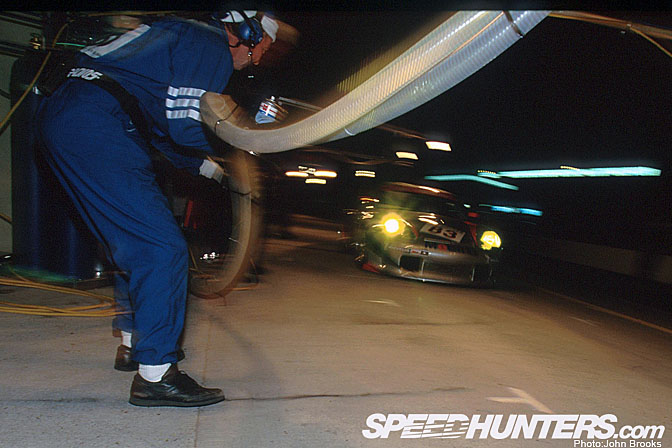

Which is of course what Audi did. In an intelligent use of a big budget they analysed that the use of hydraulic sequential gearbox combined with the effect of the two chicanes on the Mulsanne Straight put undue strain on the transmission.. To solve this issue they had their supplier, Ricardo Engineering, construct a pneumatic selection system. Furthermore the rear suspension and rear wing were mounted on the gearbox casing, meaning that the entire rear end of gearbox, suspension, brakes and wheels could replaced as a pre-assembled unit. The whole job took around seven minutes during the race and indeed, this facility would determine the final result. Not everyone approved of this ability to make wholescale repairs to the car, arguing that endurance races should be just that, endurance for man and machine. Coming from a rally background where the ability to make repairs quickly was an essential part of the sport, Audi would have found this attitude strange.

The only part carried over from 1999 was the engine as the 3.6 litre turbo-charged V8 had provided plenty of power and good economy. The rest of the car was built with the same application of thought and experience shown in the solving of the problems associated with transmissions.

In the final analysis with the R8, Audi brought a gun to knife fight, the car was better, the driver line up was equal to any, the Joest team led by Ralf Juttner had already won Le Mans four times and the really serious opposition like BMW, Toyota or Mercedes Benz had disappeared. Game over.

In reality the only people who could beat Audi were Audi themselves. Notgonnahappen.com

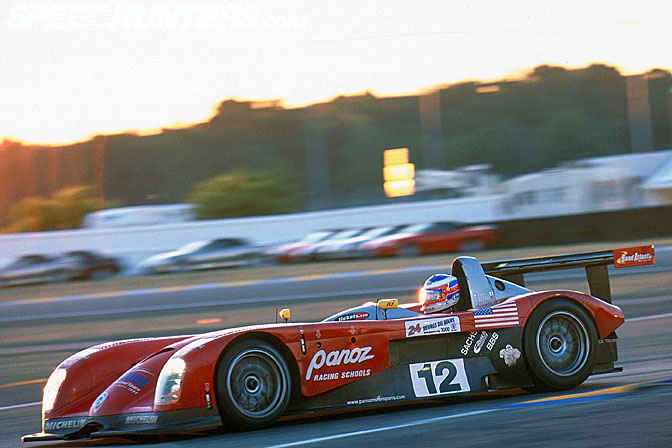

McNish took off like a scalded cat from the outset, towing #7 and #8 along with him. Only David Brabham in the #11 Panoz was able to tag along. With a Cadillac catching fire early on in the race and the safety car being deployed for 40 minutes, while things were cleared up the pis stops became a bit jumbled and the Aussie star jumped the Audis and lead for 8 laps. The natural order was restored and McNish duly lead for the next two sessions and the Audis triple stinted all three drivers.

Indeed Brabham's heroics were being matched the #12 sister car with Hiroki Katoh, Johnny O'Connell and Pierre Henri Raphanel at the wheel. It held 5th place behind the other Panoz and the Audi trio.

Never mind what #12 was up to. First Jan Magnussen, then Mario Andretti put in triple stints and the reward was third place as midnight approached. Some 60 year old! The #9 Audi, with Stephane Ortelli at the wheel had a spin at Indianapolis, a couple of hours later, the entire rear of the car was replaced as a precautionary measure, costing some 7 minutes, which would be crucial in the long run.

The stop, and a puncture for #8, promoted the #7 Audi into the lead. It held this for the next four hours till around 2.30am, Sunday morning, when it too left the track and once again the rear was swapped, 8 minutes lost.

The story at the time emanating from Audi's press police was that all three cars were treated equally and that there were no team orders, other than the obvious "Don't crash into each other like Red Bull" sort of thing. However as Orwell observed sagely, in most situations when all pigs are equal, inevitably some pigs are more equal than others.

There was another story that all three R8s were scheduled to have a rear end change, only somehow one of the drivers of #8 persuaded management that it was not necessary for his car. The excuse that the changes to #7 and #9 were precautionary after off track excursions becomes a little threadbare, when it was revealed that #8 had also taken the escape road at the Michelin Chicane. Whatever. And so it came to pass, that at the half distance mark #8 had a one lap advantage over #9 with #7 a further lap down.

The final roll of the dice happened at dawn when McNish got into his R8 at 05.58 to run what turned out to be a quadruple stint. There was a controlled fury about that drive, clearly visible to me trackside as he flogged the Audi harder and harder, eventually setting the fastest lap of the race during his fourth spell. It was his final effort to repeat his 1998 victory, spurred on, perhaps, by a sense of injustice. One thing is for certain he would never tell you. Once Allan was out of the car, the management quietly instructed everyone to hold positions to the flag, a very sensible approach.

In the rest of the prototype class it was a tale of mechanical carnage, that put Audi's almost flawless display into context. The dreams of Don Panoz and Mario Andretti were destroyed as #11 had two gear box changes, that took over an hour rather than 15 minutes that Audi have taken. #12 only had one transmission change. Despite this #12 ended up in 5th place at the finish, ten places up on #11. It was a small comfort to know that this small team had offered a greater challenge to the Audi steamroller than the other Detroit factory projects put together.

The Chrysler effort was a disaster. In #5 Yannick Dalmas lost oil pressure travelling down the Mulsanne Straight on the first lap and was forced to park the car and post the first official retirement, a dubious distinction. #6 had a nightmare of a race with an early cooling problem leading to a water pump replacement and then the first of four gearbox replacements. The car spent nearly four hours in the pits, limping round to finish 20th overall.

Cadillac's race got off to similarly poor start when the #4 caught fire in the first hour destroying the car. The mechanics had worked miracles to get the machine onto the grid after Kristian Kolby shunted it into the pit wall during the warm up. Were the two incidents connected? No one can say. The #3 car enjoyed a steady climb up the ranks till it looked as if a 4th place and first non-Audi was on the cards. Then just after Midday on the Sunday the rear suspension collapsed on the Mulasanne. Eric Bernard dragged the car back to the pits where it was repaired but also declared undrivable. The Caddy was parked for a few hours emerging to do a last lap, take the flag and be classified 19th.

That was still better than the Team Cadillac cars that 21st and 22nd overall after a catalogue of disasters including accidents, turbo, clutch, suspension and gearbox failures. It was a learning year that had been emphasised all along, well they had plenty to think about and a long list of jobs to do before they could seriously challenge the Germans.

In the early part of the race, the charge behind the Audi and Panoz teams was led by the Rafanelli Lola and the Pescarolo Courage, at least until the Lola's engine failed.

The retirements meant the best non-Audi and fourth placed finisher overall was the very popular Pescarolo Sport Courage C52, with Sebastien Bourdais, Olivier Grouillard and Emmanuel Clerico driving. A fantastic result for Henri Pescarolo. Would it tempt Peugeot to come and play?

With the result in prototypes known from the start, the race was kept alive by the competition on the GT classes. The Viper/Vette scrap was every bit as good as had been predicted. The ORECA Vipers would have the benefit having run at Le Mans for the previous three seasons. Even more importantly they could do an extra lap on a tank of fuel, a significant advantage over 24 Hours.

In the end both #63 and 64 had a couple of minor problems, as did #53 and #52.

So another triumph for #51 with Olivier Beretta, Dominique Dupuy and Karl Wendlinger having a trouble free run to repeat their Daytona 24 Hours victory. They had been pushed all the way by Corvette. It is strange to reflect that of all the American projects that appeared at Le Mans that year, only Corvette are still there. They are now part of the fixtures and fittings, it would be very odd at La Sarthe without them.

In the Porsche 911 class, sorry LM GT, the Barbour example ran away from the rest of the field, as it should with factory support and drivers. In the end though it was disqualified as the fuel tank and system were just over the permitted 100 litres. As all the tanks were supposedly standard items and only the class winner was checked after the race, it was questioned whether all the Porsches might have been excluded…………

The record books show that Team Taisan Advan' Porsche 996 GT3 R was the 2000 Champion. Driven by Hideo Fukuyama, Atsushi Yogo and Bruno Lambert, victory must have seemed very unlikely on Thursday evening after Fukuyama had smashed into the Armco down the Mulsanne Straight. All day and all night the team laboured to get the car on the grid. A win was never so sweet.

The win was all a bit last minute on the track too. Fabio Babini in Haberthur Porsche lost first his windscreen, then his position as Fukuyama barged past starting the last lap. The final insult was that the rear wheel shattered, stranding the Italian on the circuit and as the car did not take the flag it was not classified. Hero to zero. Imagine how Fabio would have felt once the news of the Barbour exclusion was announced.

Audi destroyed the field with a display that would beaten stronger opposition. The winner covered 368 laps or 5007.998 kilometers (3,111 miles) and was 24 laps in front of the 4th placed Pescarolo entry.

A new century and a new order in Endurance Racing, a fantastic performance.

John Brooks

I'd buy the book. This is exactly when I became aware of endurance racing,

Excellent stuff, and all shot on film too

where theses taken on film or digital. just curious because of the grain

really enjoyed that john , thanks

amazing write-up and photos John, i really love these retrospectives!

I miss the Panoz LMP and i hope Viper will return in the future.

The Pescarolo really is special.

Film........there were digital cameras out at the time.............you just needed to raid Fort Knox to pay for them................$25,000 from memory..............and I was not Goldfinger.