The hypercar is a relatively recent phenomenon, taking the fastest, most expensive, most extreme cars on the planet and making them, well, even faster. Even more expensive. Even more extreme. They involve a level of design freedom unknown in the normal confines of the car industry, but even a hypercar designer has to start somewhere and understand the realities involved with pushing the envelope so far.

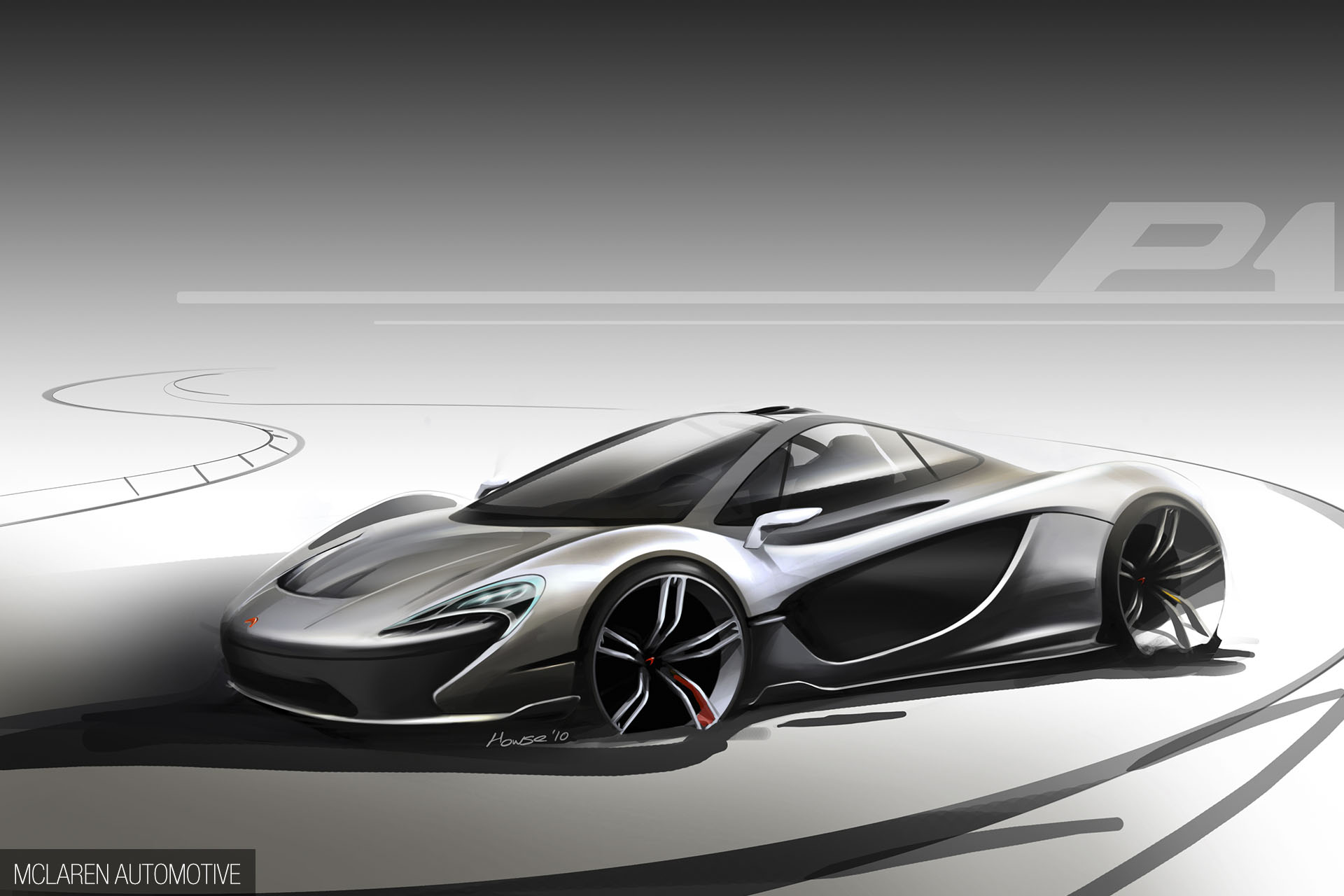

To get under the skin of designing a hypercar – and what it takes to get into the position where you’re given the crayons and the freedom to be assigned that task – there’s no better person you could talk to than a man who’s been responsible for some of the most iconic cars of the last two decades. I present Frank Stephenson, from whose magic pen has sprung McLaren’s latest hypercar challenger: the P1.

This is a man who’s career has criss-crossed the industry, managing some of the most important launches and reinventions in recent times. The new Mini. Fiat’s 500. The Maserati MC12. Alfa Romeo’s Mito. All Frank’s projects. And that’s before we get to Ferrari and McLaren.

Frank is not only an inspiration; he’s still as passionate as ever about his job. That bit is not so surprising, but how Frank got to this position is, and it’s a salutary lesson in the importance of both mental application and bohemian freedom of thought.

We sat down with Frank at the McLaren Technology Centre to talk through his background and just how you come up with a car like the stunning P1. A true cosmopolitan, Frank was born in Casablanca, Morocco, to a Norwegian father and Spanish mother, where he both grew up and also first discovered his passion for the automobile. At 10 years old, Frank was walking with his father along one of Casablanca’s main boulevards when he saw something that would change his life: a sculpture in metal; art in automobile form. An E-Type Jaguar.

Frank: “I had no idea what it was. I’d never seen anything like that before; I stood there frozen, and it took my father at least 10 minutes to drag me away. That sort of kicked off the idea that cars are beautiful and emotionally exciting, and after that I started drawing cars.”

The family subsequently moved to Spain, where Frank’s father had opened a car dealership. Frank attended school in Madrid, but worked in the bodyshop of his father’s business every Summer break. In the workshop he discovered another outlet for his growing love affair with the car by beating panels and getting into custom painting – and the sketching continued. It was expected that he’d finish his studies and work for his father, but Frank had other ideas…

Frank: “I’d seen a friend race motocross and thought it looked pretty exciting, so I asked my father if I could race bikes for a year or so before starting work. In the first year I won the Spanish junior championship; the next year I moved up to senior and won that; then the third to sixth years I raced with Honda on the GP tracks full time, which was great for a guy in his late teens, early twenties. All I did was work out, race bikes and travel! I was doing pretty good: I was top 10 all the time… except I never won. So at 22 and a half years old my father said, ‘That’s it, you’re not riding next year – you’re not good enough. Either start working or go and study’.”

What to do? Unsurprisingly, Frank hadn’t been aware that car design was a real option as a serious career, but an article in a magazine he subscribed to, AutoDesign, triggered the next stage of his life. The story was on the Art Center College Of Design in Pasadena: they’d just sponsored a Pininfarina exhibition, and Frank discovered that this was the place he’d dreamed of: a school dedicated to car design.

Frank: “I had to send a portfolio with 12 original designs for their committee to critique, to see if I was good enough – and made it through. So I went from living in Europe all my life to moving to the States. All the students were actually around my age, as most had done four years of regular college. The first day I’m sitting in class with 30 students, August ’83, the teacher walks in and says, ‘You’re pretty good because you’re the top 30 students out of about 4-5,000 who applied’. So we get all swollen up and think we’re great. But then he says: ‘But we’ve never had more than 10 who finish the course: two thirds of you won’t be here after four years’. That burst our bubble. There were actually only six of my class who finished: it was worse than military boot camp.”

But of the six survivors, how’s this for a list of the other graduates from Frank’s course and the designs they’ve subsequently worked on: Harm Lagaay (BMW Z1, Porsche Boxster); Craig Durfey (Dodge Viper); Miguel Galluzzi (Ducati Monster; now works for Moto Guzzi and Aprilia); Andreas Zapatinas (Fiat Barchetta, Alfa 145, Fiat Coupé); Ken Okuyama (Ferrari Enzo, Maserati Quattroporte).

Frank: “We’re still tight, we meet at least once a year at the auto shows and there’s usually a designers’ party.”

After graduating Frank took up a position at Ford’s European design headquarters in Cologne. His first task? Working on hubcaps for the Ford Sierra. Okay, humdrum so far. But next up came the Ford Escort Cosworth, and Frank had a hand in creating the iconic whale tail rear. 11 years with BMW was next, which saw him tackle the reinvented Mini and the X5 SUV. He then moved to Fiat for six years, starting by penning the Ferrari 430, FXX and Maserati’s MC12, then overseeing Pininfarina’s work on the 612 and Quattroporte and some work for the mother brand (500, Punto, Bravo) before finally moving on to Alfa Romeo Central Stile for the Mito. I have to reread this list several times to take in the enormity of all that.

But then McLaren came calling. They needed a Design Director, but the only thing that concerned Frank was the company’s track record: one road car 15 years ago, followed by one-offs every so often. Reassurance came from Ron Dennis, and the revelation of McLaren’s three pillar strategy for the future: an entry level sportscar to compete with the high end 911, a supercar to go against the 458 and Gallardo, and a hyper car to take on the Veyron. Frank signed on the dotted line.

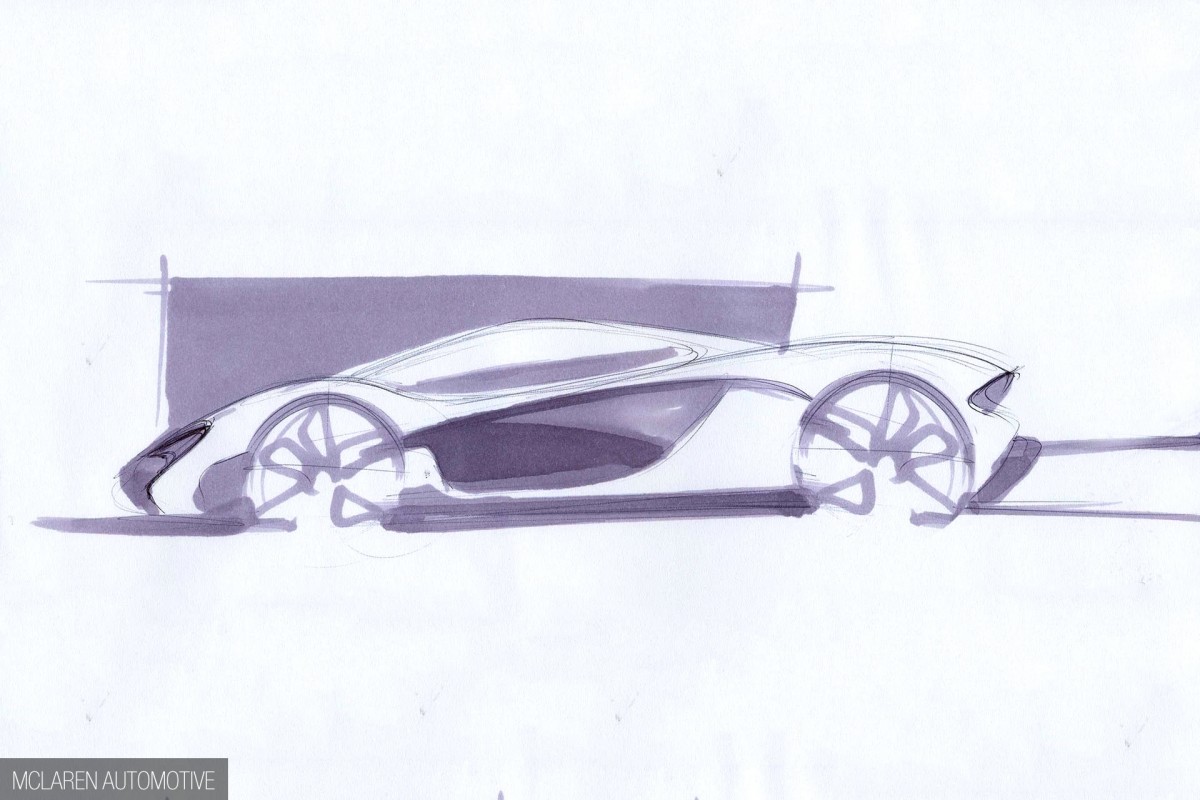

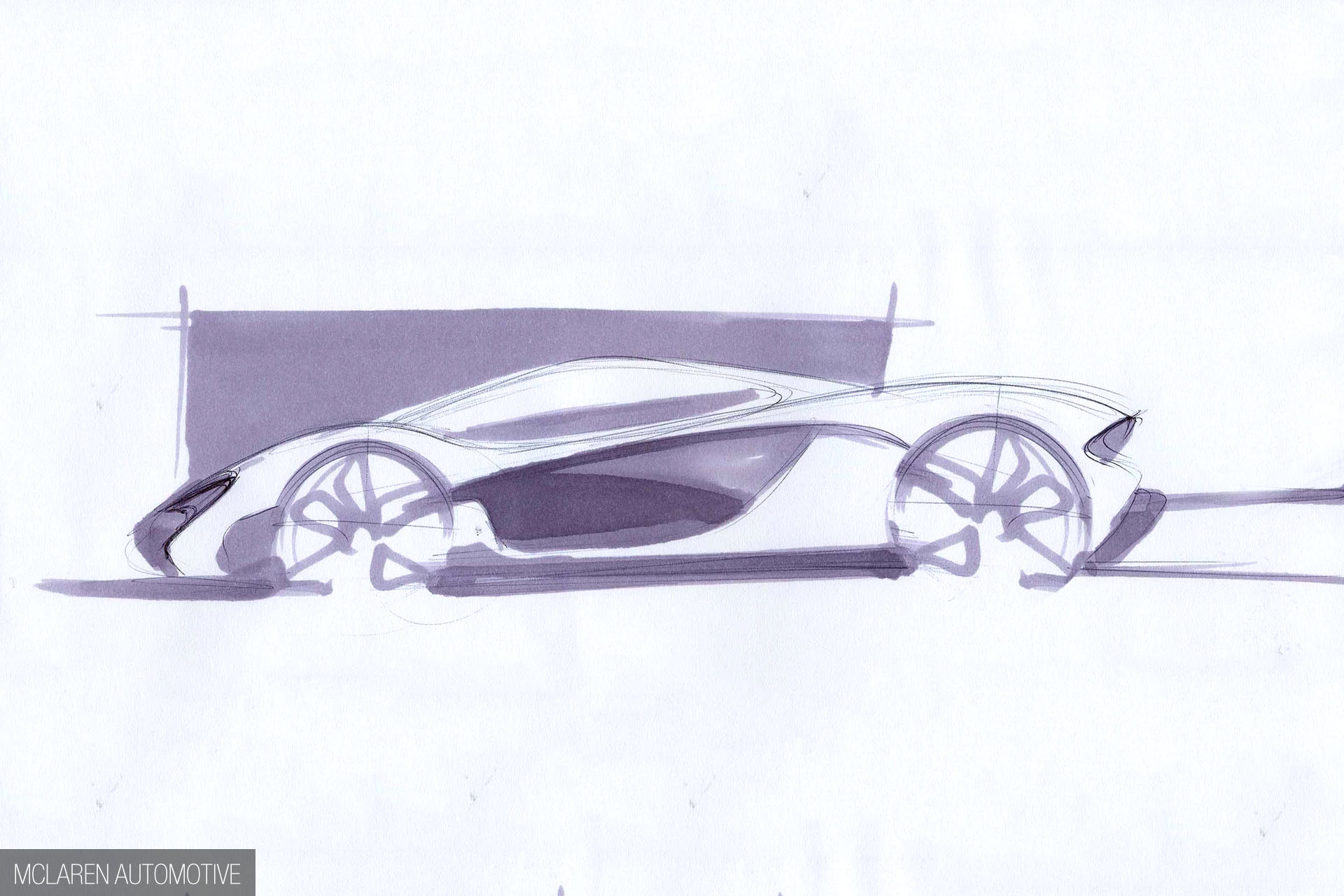

The 12C design process was way down the line when he joined, so Frank’s input was focused on the second stage of the project: the hyper car. The first step was to define what exactly this car should mean, a process which started over two years ago.

Frank: “That was my job: how do we go from not even knowing how or what we’re going to make, to the final car. Does it look like the F1 15 years later, what it might have evolved into? But we had such new technology under the skin, it would be hybrid, the suspension was all new and safety had moved on so far that we knew it wouldn’t look like an F1. And as much as people love the F1 and say it’s the greatest car of all time, it’s not that dramatic when you look at it today. It’s a nice, balanced design – you could say timeless – but if you saw it today anew I don’t think the F1 would make you scream, ‘Oh wow!’. Unlike a Countach, which looked like it had landed from another planet. But the F1 was never like that. I thought it was a sound design, well put together and not flashy.”

“I was in a lucky position, starting with a blank sheet of paper without any restrictions. No one said I had to make it Son Of F1; a spiritual successor yes, but not literal successor. It had to follow the same general principles of being innovative and fit for purpose, and no expense spared, but in the rest of it the F1 was so far back that it was like speaking about your great-great-grandfather. This was a great opportunity for a designer to not have to worry about what was in the past and break new ground.”

“From a design brief with the P1 we thought that if it’s going to be our calling card obviously we have to be very dramatic and innovative. With hypercars it’s almost like haute couture fashion: if you don’t do something outrageous then it doesn’t merit someone paying a million bucks.”

CHAPTER TWO

Starting from the inside out

Interestingly, the design process started from the inside out, with the track and wheelbase and the organs of the car rather than a beautiful drawing – they’d come later.

Frank: “We had brainstorm sessions and initially had two solutions we could have gone with: an extremely radical packaging solution, or one that based itself off the carbon tub of the 12C. Because the tub of the 12C was optimised to such a point where we couldn’t take any more weight out of it and it was structurally sound whatever you wanted to build, whether spider or coupé, we decided to use that technology as a base.

“Next we looked at the engine, the hip point between driver and passenger and what kind of visibility angles we needed. Because of the 12C platform, we knew relatively what the dimensions were going to be, but we wanted the car to interpret a new design direction for McLaren.”

“We discussed the design language and core values for McLaren: lightweight, courageous and obsessive. Buzzwords perhaps, but they helped us as parameters and made us think about what would fit that ethos – they also meant a licence to do anything we wanted! Firstly we thought about weight. If it looks light, it generally is light. I referenced a cheetah’s shoulders; those sinuous, fast looks. So instead of going and adding sensual surfaces we pretty much stuck a tube up the exhaust pipe and sucked all the air out of the car! We shrinkwrapped it across the hard points of the car: the suspension mounts, visibility angles and so on, reducing the whole volume of the car. It’s the idea that you stand behind it and think, ‘Wow, I’ve never seen anything like that before!’. We pulled everything in mechanically to the middle of the car. We made it look like the car was malnourished!”

“Beauty is subjective; there’s no formula and it’s hard to define what is and isn’t attractive, so when you’re trying to come up with a unique design language it’s pretty hard. It’s like when Picasso came out with cubism: he went away from what everyone thought was real beauty, traditional Monet and Rembrandts. He did something that blew everyone’s socks off because it was so different: it was a new approach that broke conventional appreciation of art and found a new style. That’s the holy grail of design: to grasp a design style that stands out on its own.”

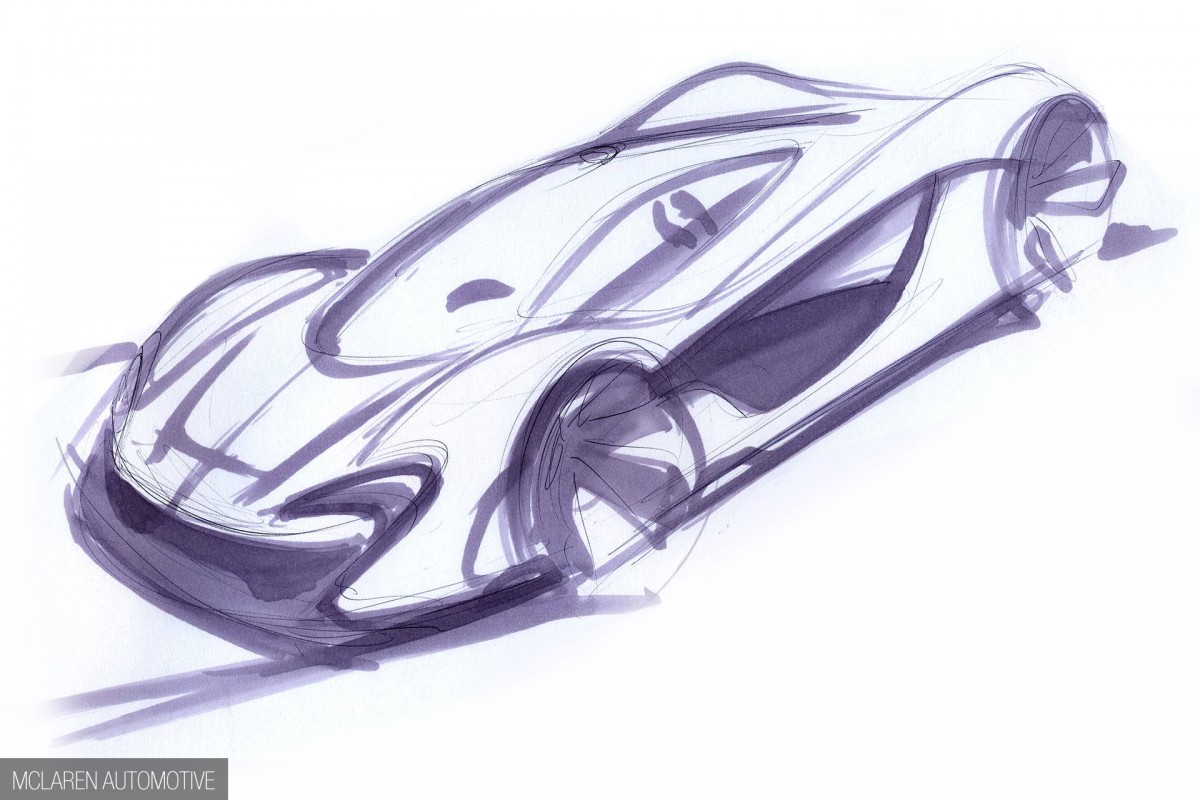

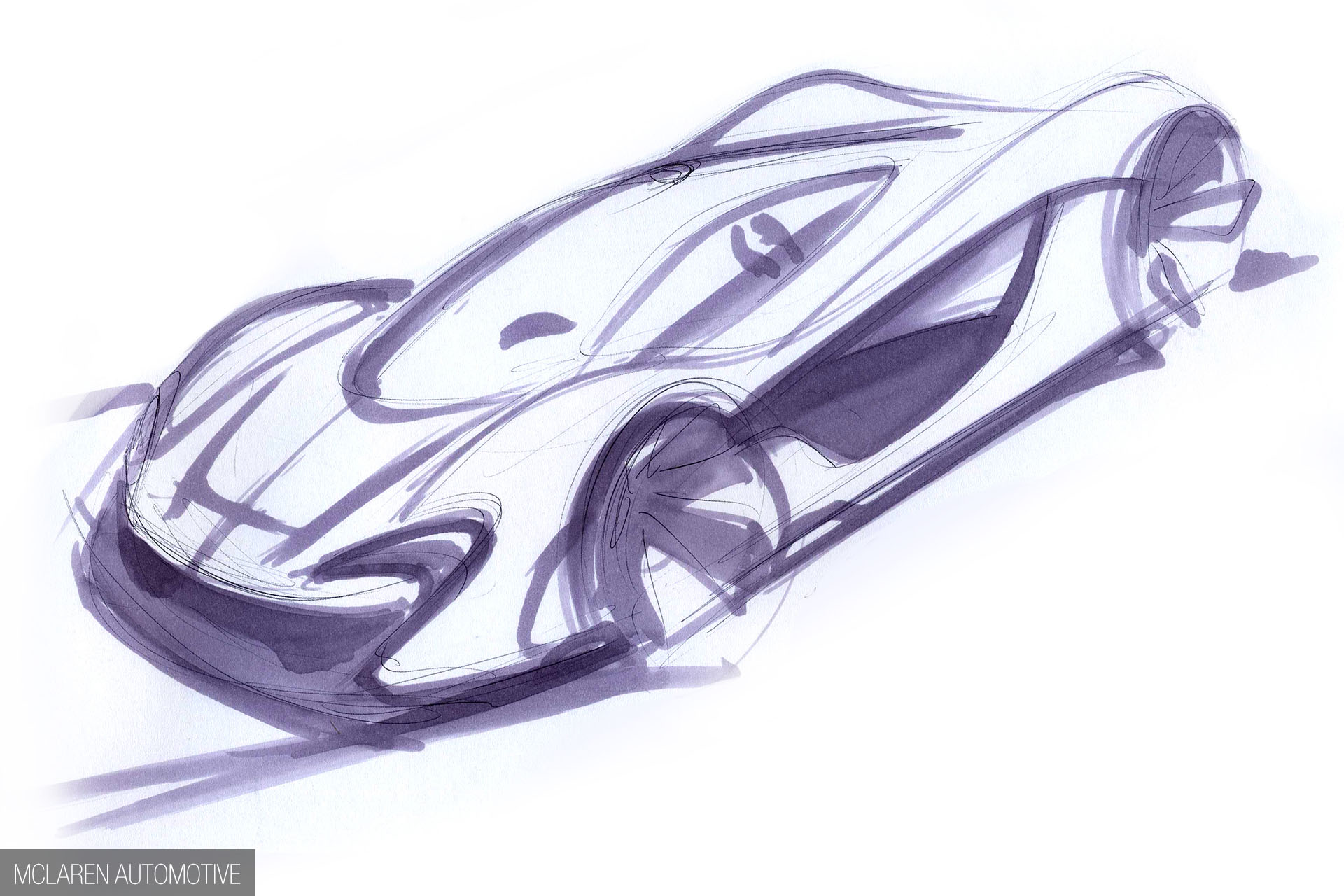

There’s an unexpected combination of influences that came together in Frank’s mind to define the look of the P1. Nature, sure, but then… military aircraft? But it does makes sense.

Frank: “It’s about articulating concepts. My interest has always been nature – and military aircraft. It wasn’t about looking for something ugly or aggressive, but we wanted to examine objects that are seen as being naturally cool, like military equipment and animals. None are designed for beauty specifically: they’re absolutely functional. That’s why animals look like and do what they do.”

“Form doesn’t follow function: you design something to work and it looks beautiful because it’s effective. It’s not like horses or cheetahs are ugly because they’re designed to go fast, they are what they are, and the cool thing is also that they’re timeless. If you take the approach that the car itself has to be ultimately effective, and then put a designer in there to fine-tune things without destroying any performance advantages that you have from that original design, then you’re going to have a car that is very technically designed.”

FINAL CHAPTER

Reading organics: the fluid body

There’s a reason that the car has such an organic look, like the bodywork has been draped in liquid form over the P1.

Frank: “A lot of companies now rely on CAD for speed of development, but the last thing you want is for a digital computer to tell you what line to draw. It just connects three points in space – that doesn’t work in the natural world. You won’t see design like that: you have to do it by hand. That’s why if companies aren’t using clay, they’re going against nature. It doesn’t feel right! A lot of it is about feeling, about surfaces. Sometimes you don’t even have to look at something, but you can feel it and be in tune with it to know if it’s right. It’s a tactile thing.”

Once the overall look of the car was nailed down, there was then an iterative process using CFD for pre-wind tunnel testing, analysing different speeds for downforce and lift.

Frank: “Everyone talks about aero being important, but it’s not for a hypercar. All you want for a car with over 900 horsepower is for it to stay on the ground. You just don’t want it to take off. Who cares if it slips through the air: horsepower will punch through a headwind and still go 200mph. So what you want aerodynamically is the opposite. We were more concerned about creating drag, so we concentrated on the diffuser and aero underneath to suck the car onto the road, plus the big wing that pops up.”

“So the P1 isn’t that aerodynamic: if I gave you the numbers you’d be completely unimpressed! Whereas city cars are all about fuel economy, the more slippery the car the better economy, plus they want to reduce wind noise – but they aren’t really values we’re concerned about. We just want to drive around a corner at five times the speed of a normal car.”

One of the noticeable things on the P1 is the use of the McLaren swoosh logo across the car.

Frank: “It’s funny how that’s been criticised. Sure, if you start putting too many logos on it’s a bit much, but all of them have different proportions and it’s a very effective shape for bringing air in and channeling it out. It’s not a NACA duct, but it works very well aerodynamically and if you can design an element styling wise, and it doesn’t screw up the performance of the car, then at least we get to get some McLaren design DNA in there. For me, headlights are like the eyes on a face: they give a car character. It’s not to say that every headlamp we do from now on will be exactly like the logo, but it’ll evolve like anything else: they’ll look slightly different.

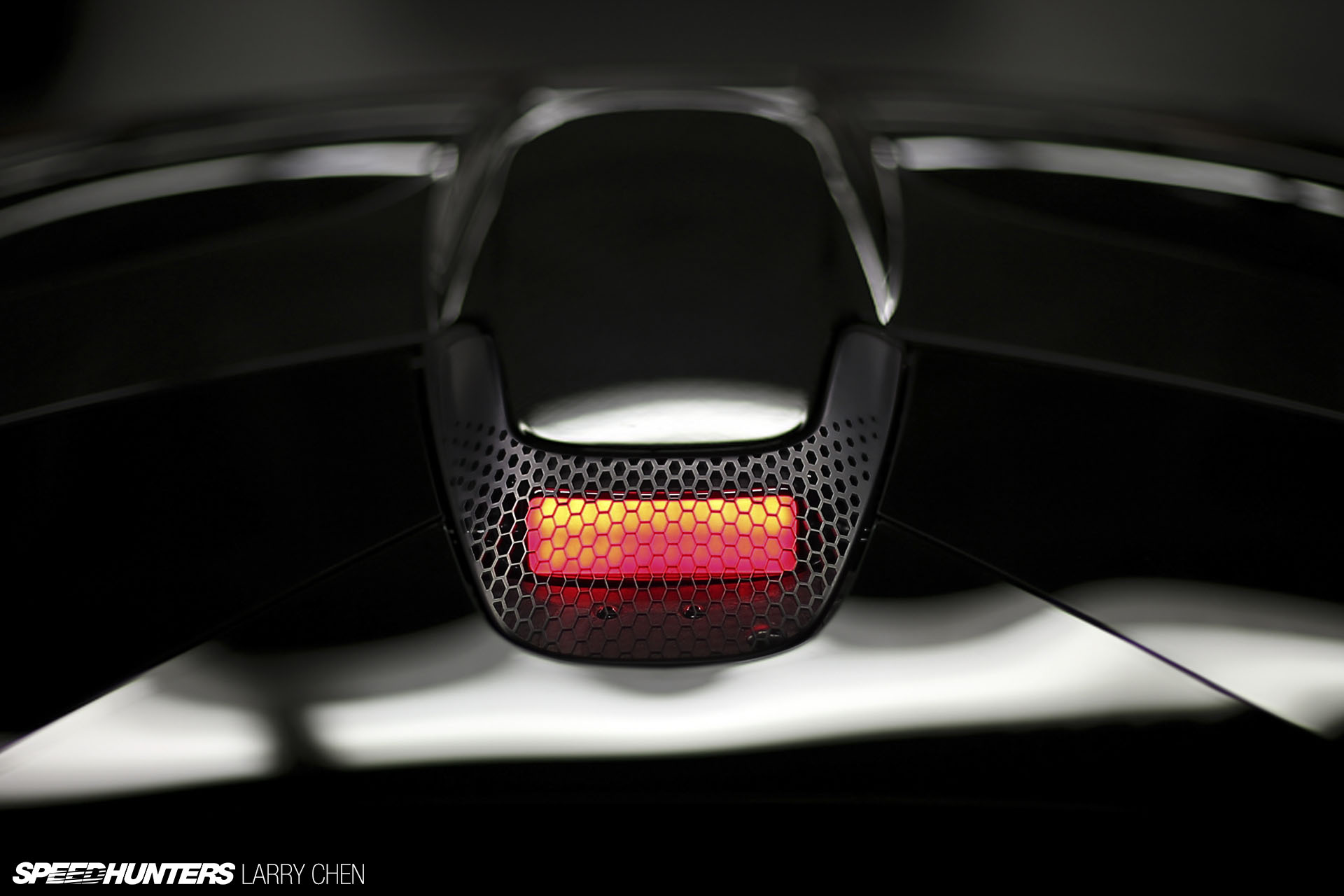

“If you look at our tail lights, they were designed because we had so much hot air inside the engine bay that we had to get out. We designed it without a rear end, like a racecar. If we’d put regular tail lights on it, they would have covered up the the area again that we were trying to push the heat out from, so the tail lights became the long trailing edge highlighting the rear of the car. Each LED has a cap on it which disperses the light and stops hot spots. It’s more like a neon glow: it was about making a nice glow of light rather than a line of hot spots.”

“The reverse and fog lamps are integrated into one slim little unit just underneath the number plate: they’re dual function and go red or white as necessary.”

“The third brake light is in the back of the roof scoop. We called it the CHMSL: Centre High-Mounted Stop Light. The mesh is titanium because it also serves as exit chimneys to take heat out of the engine bay. The mesh masks the rear light as well, making it look like hexagons.”

The P1 is one seriously low car: you’d trip over it were it not for the bright yellow paint. The only place to fit the fuel filler was under an access panel on the roof, but with such a low car it’s not like you have to stand on tiptoes to reach it. The oil filler sits in a symmetrical panel on the other side of the car.

Frank: “The rear deck is as low as we could get it. Sitting in traffic everyone is looking down at you: it’s got a completely different context in public – even we were shocked! In the studio we had nothing else to compare it to, but when we took it out into the parking lot we were like, oh… we didn’t think it was that low!”

Often there are fights between the engineering and design sides of car companies, but McLaren’s structure made sure that was eradicated.

Frank: “The biggest difference between McLaren and other car companies I’ve experienced or know about is that we have to do all our car projects so much more quickly than a normal company. Typically it could take three to five years to put a regular new car on the road: we can’t do that as we’d be losing money for ever, so we have to get our cars out there very quickly. We’ve cut all development time down to 18 months, which would be crazy for a normal company.”

“To turn a car around in that time you can’t have the normal process of sticking designers behind a locked door and letting them pour out their enormous creativity to come up with a concept car that can never be built in reality. We just put our race engineers right in with the designers from the very beginning: they’re as crazy as the designers and we knew we’d get better ideas because the engineers would know what would actually work.”

“Being a small team helps, as we can update and modify as we go along: it’s the McLaren race team DNA coming through – that’s why we can do it. If you look at a car engineer and a race engineer, the car engineer worries about cost, whether they’ve done it before, whether it will break and so on. A racing car engineer; his only job is for next week’s car to be faster than last week’s car! They don’t care about cost, they just try things. It makes them feel alive; they’re not slow workers, wondering about getting home. I wish you could come in and watch how our guys work: it’s like the stock market!”

“We’ve got two hardcore designers who are working flat out, but they know that anything they draw will go into production. If you’re a designer you want a result. They’re not frustrated because their work doesn’t get chosen, and you learn a lot more as well. It translates across the whole company: everyone is working so hard, because time constraints are so tight and ambitions so big that everyone knows that they need to put their heart into their work. You can’t afford to drop behind.”

Frank sees carbon as the standard road-car technology of the future, and the reduction in time and cost of manufacturing carbon tubs in the last decade or so would seem to back up that view: from 3,000 hours for the original F1 to 300 hours for the SLR and now four hours for a 12C MonoCell.

Frank: “It’s natural progression. It shouldn’t be just for high-end cars. It is needed: it’s lighter, stiffer and safer. If you could build every car with that technology you would. For us, we hadn’t ever invested in alloy, and carbon is the best thing for racing. It’s put us in a good position for our next sportscar: Alfa have already started with the 4C, but maybe in the future we could be making tubs for another company to make super safe city cars.”

“Alongside carbon there’s a whole load of other technologies coming in, like suspension, infotainment systems, lighting… we’re going through a huge change. Everything’s out there; it’s not like we’re developing anything new, you just have to capture it. 30 years ago the technology we’re talking about today would have seemed impossible – though 50 years ago they thought we’d have flying cars by now!”

There’s also the question of the future of the supercar – and of the whole idea of the car in general.

Frank: “Future direction might be more about that simplification and the amount of features a car might have, and less like something going from here to there. Whether it’s ways to communicate, changing colours – like an iPhone that has so many features. The modern idea of thinking about the planet, reducing pollution and noise: that basically kills off the old school supercar, which is the complete opposite of all those values. Maybe when the next generation grow up they won’t care about hypercars any more – it’ll be like wearing a diamond Rolex…”

Frank naturally keeps an eye on the competition, but only out of interest – or apparent horror sometimes!

Frank: “Everyone wants to look different, but some just don’t look pretty. Like the Gumpert Apollo: you’d buy that for power, but you sure wouldn’t buy it for its looks. Or you can make something look aggressive, like the Veneno, but that’s the easiest thing in the world. But we’re all doing different things and taking different approaches, which is pretty cool.”

“As a designer you normally have to do what the client wants, but with McLaren my beliefs coincide with the way I’m designing cars now, so I’m actually really happy. If you’re designing the ultimate hypercar, the supercar should be the one that is beautiful and all that, but the hypercar should be extreme – and go really fast.”

Frank has the whole hypercar thing nailed, and I can’t wait to see what McLaren’s ‘entry level’ car might look like. But I bet it’ll go really fast…

Mclaren P1 nice job its seems like realy good car

Bütün araçlar açılışın

They open like lomborgini galardo lp

Mclaren are a good cars makers they want cars look sports

This is the best car EVER! It is in forza motersport five

Bugatti is so much better

My dad has Mclaren

My dad has mclaren

زیبا، چشم نواز، بی نظیر و در کل شاهکاری از کمپانی مورد علاقه من مکلارن...I LOVE YOU MCLAREN

I don't have it in my hot wheels box

They posted for this car.

Mclaren P1 is a very good car. I have the Mclaren P1 in GTA 5 online.

I need to get these cars

Bugatti sucks because Volkswagen have owned Bugatti since 1967

It looks good

I got this car on real racing haha with porsche 919 hybrid 2014

My mom has a new car and it's a Toyota

Epic!!!