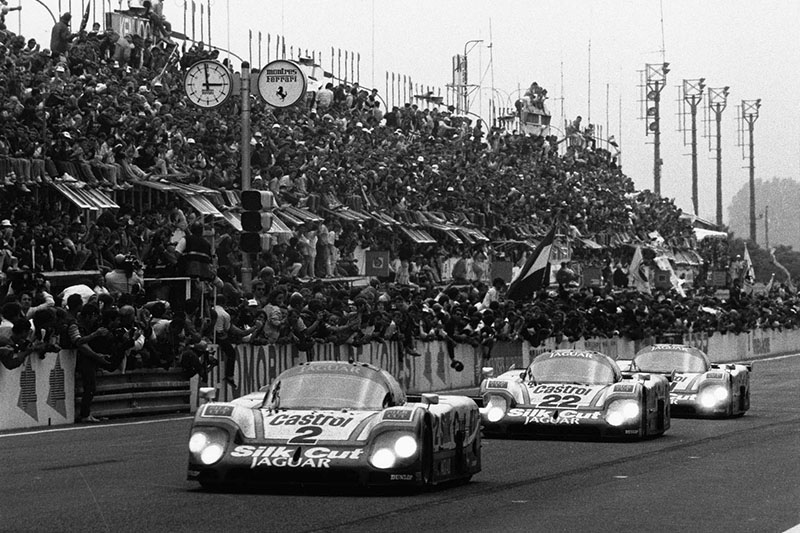

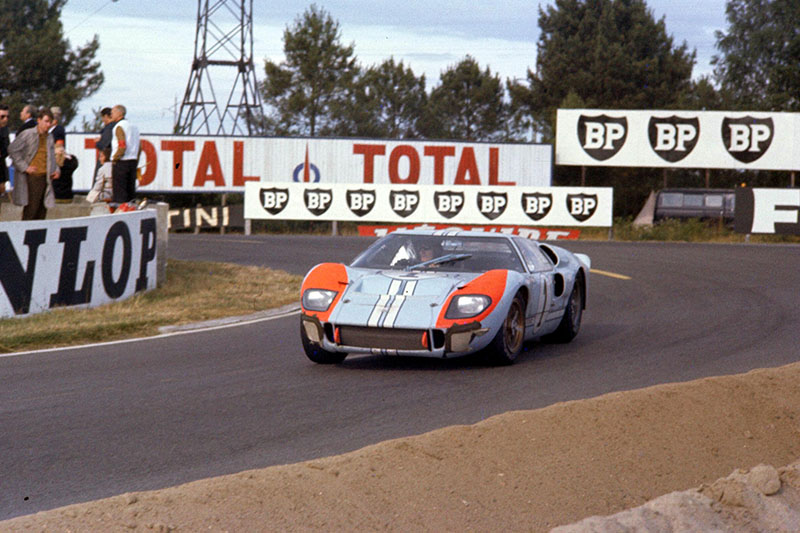

Indianapolis. Monaco. Le Mans. Three places that even non-motorsport fans would identify as representative of the spirit of racing, and the Holy Trinity of races that any driver worth his salt wants to have on his CV. Each of them is the epitome of their style of racing: Indy for high speed ovals, Monaco for its narrow, unforgiving streets and Le Mans for long lap, massive top speeds and endurance format. Mention a 24-hour race, and the chances are that the default response is ‘Le Mans’. Show a picture of a Gulf Ford GT40, Rothmans Porsche 956, Jaguar XJR12 or an Audi R18 and it’s the same. Le Mans is endurance racing.

Racing first took place around the city of Le Mans right back in 1906, with the French Grand Prix held around an enormous course laid out on public roads to the east of the city. The layout described a triangle ranging from La Ferté-Bernard in the top right corner down to St Calais in the bottom right, north-west to the outskirts of Le Mans at St Mars La Briere and then north-east back to the starting point. A single lap was over 64 miles long. The straight from St Calais was almost 15 miles long. This kind of epic size was typical of the time: courses were defined by hard things like houses and trees rather than nice big run-offs and gravel traps.

In 1911 the track moved close to its current location: a mere 33-mile layout with a long north-south straight through a small village called Mulsanne and down to Écommoy, then north-east through St Mars L’Outile and north-west to Parigne L’Évêque. These roads still exist for the most hardcore of Le Mans completists to trace…

Come 1921, the circuit was flipped on its Mulsanne axis and reduced in size to become the template for today’s track: the Hunaudières straight, Mulsanna Kink and corner, Indianapolis, Arnage and the start-line position all date from this period, with an additional triangular cap pushing north into the city suburbs and the Pontlieue hairpin (above) before running back down to the Tertre Rouge kink and on to Mulsanne.

The French Grand Prix were followed in 1923 by the first running of a new concept : a Grand Prix for Endurance and Efficiency run on the 11 mile circuit over 24 hours on the weekend of May 26/27. The original race saw 33 cars take the start, and incredibly 30 of them finished. The winner during this early period was based on distance rather than position (a rule that would even catch Ford out in ’66); a Chenard & Walcker Sport came home first, with Bentley winning the following year, Lorraine-Dietrich in ’25 and ’26.

Next was a period of utter domination by two marques: Bentley to start between ’27 and ’30 and then Alfa Romeo from ’31 to ’34. During this period the track also underwent small changes, the first of 14 contractions and shimmies that have evolved into the track we see today.

The run into the suburbs was cut down between 1929 and ’31 and then in 1932 removed completely with the creation of the link from Dunlop (complete with two Dunlop Bridges) to Tertre Rouge (shown here) via the Forest Esses. The track, essentially, was set for life.

Looking at a sequence of pictures of the Forest Esses there’s basically been no change in the track except for the trees thinning out and the banks retreating. 1952…

1966…

1975…

2003. The cars have altered dramatically, but the Forest Esses are same challenge they ever were. It’s the story same around the track.

Concrete kilometre marker posts used to line the track – some of which can be seen in the Le Mans Museum, which we’ll be featuring in a forthcoming story.

The pits were completely rebuilt in 1956 following the horrific accident for Mercedes in 1955, when factory driver Pierre Leveigh and 80 spectators were killed when he crashed into the crowd on the start straight.

The smart whitewashed concrete and slanted front was cutting edge for the time, and presented a sparkling modern image for the circuit.

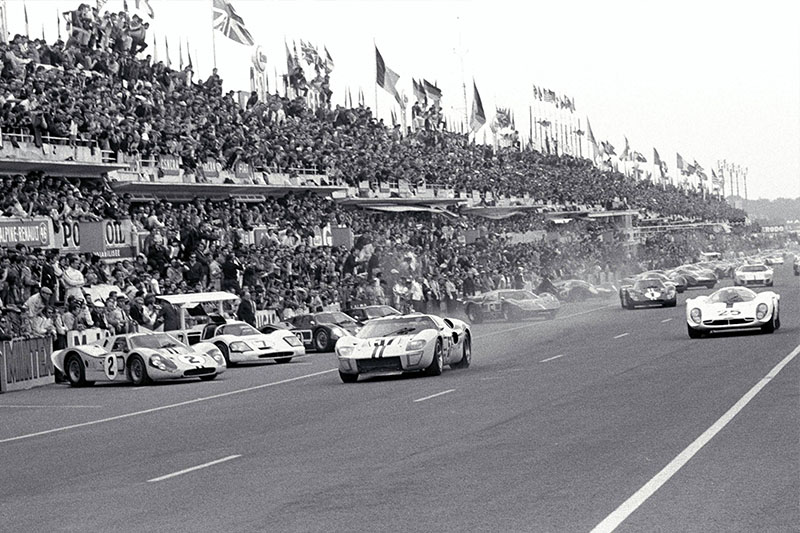

Come race-days the building disappeared under the sea of people, giving the impression of an avalanche of people overlooking the open pit-lane.

This is one thing that has never changed about Le Mans: the vast numbers of people that the race attracts every year.

Hundreds of thousands of fans cram the bleachers and tribunes overlooking the straight, creating a tunnel-like area where the noise of the cars can be rivalled by the spectators. It’s always one of the special things about Le Mans at night: seeing the cars arrive out of the darkness through the Ford Chicane and power up through the middle of the floodlit grandstands before disappearing again into the night.

It wasn’t until 1971 that someone had the crazy idea that it might be a good idea to separate the track from the pit-lane with a ribbon of Armco: previously the only protection for mechanics and drivers had been a painted white line…

This iteration of the pits lasted until the modern glass and steel complex was constructed at the turn of the century, and made for some iconic images.

There were no more major changes to the track until 1968, when the interior Bugatti circuit was built to allow national racing to continue without having to close local roads, and the Ford Chicane inserted at the entrance to the start/finish straight. This layout still included the fearsome Maison Blanche section, which was a deceptively difficult kink in the long sweep from Arnage to the finish.

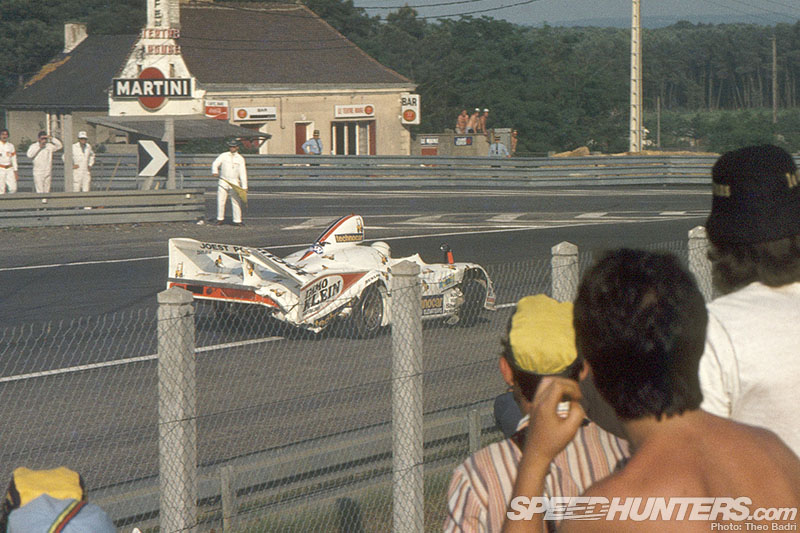

Looking at images from before the modern period, even though the corners themselves are recognisable the biggest difference is in the run-off – or lack of it. The circuit was virtually a street circuit, with barriers lining the track right at the edge of the tarmac.

Wooden palisades gave way to concrete walls, with sand banks seen as the appropriate solution to cars running wide on the exit of corners. Yes, in retrospect, not the cleverest idea, especially in mind of the number of cars that hit the banks and turned over or the effect of hitting a sand-bank that had been soaked with rain for several days, giving the equivalent of a concrete barrier. However, thoughts on safety are always relative in this period. It just didn’t occur to people that maybe it might be a good thing to keep drivers (and spectators) in one piece when there was fine motoring entertainment to be had.

First used in 1925, the Le Mans running start lasted all the way to 1969, when Jacky Ickx famously boycotted the tradition and sauntered to his car, narrowly avoiding being run over by another driver who wasn’t so bothered, and properly did up his safety harness before joining the race. Ickx’s point about safety was made even more relevant by a Porsche privateer being killed in accident at Maison Blanche on the first lap of that year’s race, his life likely lost due him not having secured his belts.

Steve McQueen’s 1971 film Le Mans is a fantastic way of experiencing the track as it was in period (in the same way that watching Grand Prix takes you back in time to the tracks of the 1960s). He entered a Porsche 908 in the 24 Hours itself, mounting a camera which captured some incredible on-board images, and mixed the result with footage both taken during the race and action sequences shot afterwards. Showing the era of the Porsche 917 and Ferrari 512, it’s a time capsule of a golden age for Le Mans.

Maison Blanche – the White House – was a notorious accident black spot, so in 1972 the entire section was bypassed with the construction of a completely new combination of corners to be called the Porsche Curves. The Ford Chicane was also doubled to its current left-right, left-right combination.

In 1979 Tertre Rouge was re-profiled and made tighter due to the creation of a new public road section – one of the most frequent reasons for changes being made to the track.

The exit of Tertre Rouge dovetailed into the main road, and up until recently you could still inveigle your way around the barriers on the outside and watch the cars disappearing into the distance down the Hunaudières straight.

The famous track-side bar at Tertre Rouge has become more and more obscured in recent years…

But take the tunnel under the track and the bar itself is always heaving with race fans. On the years where the Canadian GP runs on the same weekend as Le Mans, there’s no better place to watch the F1 race. Similarly, the famous restaurant just before the first chicane on Hunaudières is also covered up behind protective fencing.

All through its existence the majority of the circuit has predominantly been made up of public roads – most famously the Hunaudières straight. Accidents (on this occasion of the road rather than racing variety) had led to the installation of a roundabout at Mulsanne corner in 1986, perhaps due to too many people pretending that they too were driving a Moby Dick… A new short link was constructed inside the main road leading to a new, tighter Mulsanne corner slightly offset from the original.

In ’87 the Dunlop Chicane was added to slow cars down as they crested the hill, removing the flat-out blast up and over the hill that had been in place for the previous 60 years.

Although chicanes are never really that welcome, the Dunlop Chicane makes for great spectating: the uphill entrance has a difficult camber through its braking and turning phase, leading to plenty of locked wheels, spins and worse.

The most controversial change since the removal of Maison Blanche came in 1990, when two chicanes were inserted into Hunaudières due to an FIA directive on the maximum length allowed for straights.

This split Hunaudières into three sections and transferred the honour of being the fastest part of the track from Hunaudières to the run from Mulsanne to Indianapolis, previously something that seemed like a relatively short blast after the flat-out eternity of Hunaudières.

The Mulsanne Kink after the second chicane now opens out onto a liposuctioned Hump, reduced in height after the flying Mercedes of ’99.

The final major change was the creation in 2001 of a sweeping S-curve on the run down from Dunlop to the Forest Esses, removing the classic sunset shot of the original arrow-straight descent under the Dunlop Bridge.

The main reason for this change was to ease the entry from this section into the interior Bugatti circuit, which had been causing particular problems for bikes, but it’s difficult not to lament the loss of the classic high-speed run down into the Forest Esses.

More recently, Tertre Rouge has been smoothed out to create a longer, more flowing entry onto the Hunaudières straight, and minor changes made to Arnage. The Indianpolis/Arnage section, like the Forest Esses, is another part that has remained constant.

The current track weighs in at a healthy 13.629km, with the fastest prototypes putting in laps under the three and a half minute mark and the GTE cars under four minutes.

Nips and tucks aside, the general line of today’s track is a good 80 years old: proof that if something works you should leave it alone. Now, if only we could ditch the chicanes…

Le Mans has been the proving ground for cars for almost 90 years: manufacturers still queue up to compete at the race, and the track has witnessed the mutation of sportscars and their aerodynamics from the solid-front upright bolides of the 20s to the streamlined racers of the ’60s and and the sci-flyers of today.

The race has always provided a mix of challenges that have provided a platform for innovation: cars must achieve as much speed as possible on the straights but also make it through the twisty sections like the Porsche Curves – and now also the chicanes.

That means brakes are as important as top speed: lovely though it is to cruise along at maximum velocity, it’s also nice to know that you’ll be able to stop come the next corner. Jaguar introduced disk brakes at Le Mans in 1953; Mercedes used an air brake on their 300 SLR of 1955 and modern carbon brakes provide stopping power that could only previously have been dreamed of: cars now seem to touch the brakes impossibly late for corners. Sometimes too late, but still…

Because the rules for the race have been mostly jealously guarded by the local racing club organiser, the Automobile Club De L’Ouest rather than dictated to by international bodies, the 24 Hours has also seen an incredible amount of innovation: superchargers, rotaries, gas turbines, diesels (first seen in 1949), bio-ethanol and now hybrid electric racers and Deltawings. Le Mans is the original proving ground, and long may it continue to be. Another true temple of speed.

Jonathan Moore

Additional images courtesy of Theo Badri, Porsche, Ford, Daimler, Jaguar and Bentley.

Nice!

Great article Jonathan! This is in my Top3 events to go to!

Mazda 787B, the one and only Japanese make to ever win it!!!

http://youtu.be/81zhOQ5PvaE

For a Le Mans Historic piece, missing Porsche 917 is a sin...

For a Le Mans Historic piece, missing Porsche 917 is a sin...

Very good article detailing the changes to the track - thankyou. Re Porsche 917 - its an article about the track not the cars...so photos represent that and the cars are what they are...

it is because of Le Mans focus on new innovation that really brings out that competitive spirit of the manufactures and drivers. I love seeing all the new technologies getting pushed to the limit, finding out their breaking point, refining that tech and making a better version for the next race. Cant wait for next year.

787B Mazda rocks.... Real shame Mazda are returning with a diesel.... Should be with another rotary.... Shame on you Mazda!

70¨ Real race car !!!

@Pete the perfect pilot Would be cool if it was a two stroke.

"Speed Merchants" also as some nice footage of the era...