Party like it's 1999!!!

OK the year was given some special significance in some areas and by most folks as it marked the end of a century, whether the sense of fin de siecle was real or induced mattered not, change was going to come. I mean, "Things can only get better" so the politicians' siren song went.

The Le Mans 24 Hours was subject to the same forces that assaulted us all that year, a physical manifestation of this was the presence of brand new pits, paddock and administration buildings. In a deeper sense the year also marked a change in the approach that teams would take to the race. Some of this was driven by outside factors, some by a dose of money that had been lacking in the most part since the disappearance of the factory teams with the death of Group C in 1993.

The idea that a conservative stategy, nursing the car during the race, to stumble exhausted across the line at 4.00pm on a Sunday in June would be sufficient to win Les Vingt Quatre Heures du Mans was about to be discredited.

The arrival of the factories en masse in 1998 had sent budgets through the roof and it was clear that privateer efforts such as Joest, who had snatched victory in 1996 and 1997 from werks GT projects from Porsche and BMW, would not be allowed to do so again. A different philosophy was now being brought to endurance racing to propel it into the world that top Formula One and Rally teams inhabited. Maximum Attack!

I mention the rally teams because that is the background of two of the main protagonists in 1999, Toyota and Audi. Sure Toyota had challenged at Le Mans before but that was run by TOMS in Japan and their satellite operation in the UK. Now things were run out of Cologne, the base of Toyota Team Europe who had one eye on the future and Grand Prix racing. Audi had brought the word Quattro to the world in their rally campaigns and were renowned for the high quality of their engineering.

The philosophy of racing at Le Mans had largely followed the pattern set out by Porsche of incremental improvements to cars that could, for the most part, be run competently by customers. There had been a brief period when at the climax of Group C, the sophistication, complexity and cost of the projects from Jaguar, Sauber Mercedes, Toyota and Peugeot had rendered that approach obselete. The disappearance of the factories after 1993 had meant the return of essentially customer car racing, if you had the money you could buy a McLaren or Porsche and go racing, and be competitive, at least that was the theory.

Parallel to this was the exponentional rise in the cost of competing in either Formula One or World Rally. So driven by cost/benefit analysis Le Mans was back on the radar of motor manufacturers' marketing departments, for a fraction of the budget required to be on the grid at a Grand Prix you could get bragging rights to success at the world's most famous race. Unlike F1, failure in successive races would not be seen by millions each fortnight, so even the disasters that had befallen Mercedes Benz and BMW in the 1998 24 hours had passed largely without comment by the general public.

The presence of manufacturers encouraged the participation of tyre, fuel and other commercial sponsors, more money into the pot. The Automobile Club de L'Ouest also began to realise the value of their brand to the wider world and in 1999 launched their first franchise operation, the American Le Mans Series. Not only did this give participants in the great race somewhere else to compete under the same rules and North America to boot. It also removed the likelihood that the FIA would try and assert control of sportscar racing again or rather sportscars' greatest asset, ruling out the possibility of a repeat of the actions that led to the destruction of Group C.

Another major change was in seen in the reliability of components and cars. Driven by the huge budgets available in F1, the need for total reliability was now an achievable aim, the likes of Ferrari would go whole seasons without engine failures, even while revs climbed into the stratospheric levels above 20,000 rpm. The increasing sophistication of computer modelling meant that much less was left to chance and that the edge could be approached with a great deal more confidence. The days of making great improvements in performance by luck and a bit of sound judgement or instinct were at an end.

The change in philospohy to a more commercial manner also led to the manufacturers becoming much more aggressive in their approach to the rules and how to bend them to gain a performance advantage. In 1998 BMW had stood by and watched Toyota, Mercedes and Porsche take this line, while they had run a conventional two seater, twin roll hoop arrangement. This had unfavourable consequences in speed and fuel economy that were substantial, so for 1999 BMW and Williams were going to the edge to gain the ultimate in all round performance. Experts in homolgation and what the rules would really allow, like Peter Stevens, were consulted and the result was like a single seater with covered wheels, OK a bit of a simplification but you know what I mean. The most obvious change from 1998 was the single roll hoop that was sneaked in by reference to an obscure piece of the ACO's regulations concerning roll hoop construction and design.

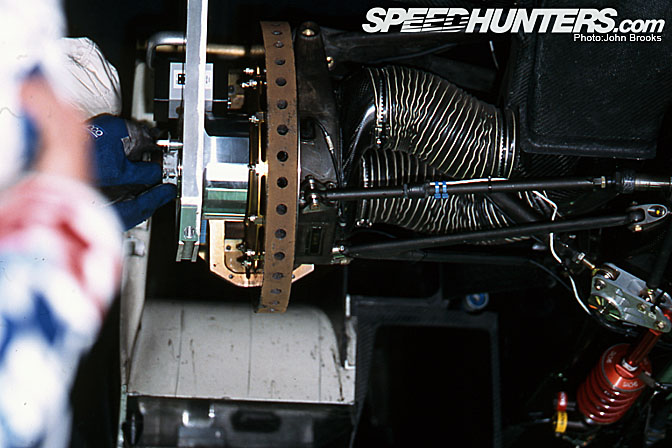

The roll hoop change had a substantial impact on the aerodynamics of the car, dramatically improving top speed, fuel economy and general stability at speed. The V12 LMR retained the raised footbox but revised the cooling system and airflow to make the car less dependant on ride height adjustment to improve this area.

Power came from the 6 litre V12 that had its ancestry in the 1995 F1 GTR engine but had been subject to a series of regular revisions. For example the weight of the engine installed in original road going McLarens was 266 kilos but by the time the V12 LMR hit the tracks four years later this was down to 145 kilos, similar improvements could found in every area of the engine. Power was around the 600 bhp mark with torque quoted at 500ft/lbs. The transmission was a six speed sequential system from X Trac and the package weighed in at around 910 kilos.

Particular attention had been lavished on the brakes which came from Hitco and were carbon. The plan was to run these through the race without changing either disks or pads, thus saving at least five minutes in the pits. In the end both cars had a pad change at around halfway through the race but not the disks gaining them a lap on the opposition. The effect that this had on both Toyota and Mercedes is difficult to quantify but it is certain that BMW's plan would have figured in the calculations of both teams and would have increased the pressure to gain time on the track to make up for that expected to be lost in the pits.

So BMW had a fuel efficient, fast vehicle that had already won a car breaking event early in the year, this was a good place to start the Big Race from. The driver line up was equally top rate. The lead car was crewed by the super fast trio of JJ Lehto, Joerg Muller and Tom Kristensen, TK and JJ both having Le mans wins to their credit. In the second car, if you can call it that, was Pierluigi Martini, Yannick Dalmas and Jo Winkelhock, all vastly experienced, with Dalmas a winner in La Sarthe in 1992, 1994 and 1995.

I spoke with Allan McNish about driving tactics at races like Le Mans and he said that from 1999 it is absolutely flat out all the way, every lap is driven as fast as the car will go. He was in the Toyota team back then and he described the car as very fast, edgy and difficult to drive on the limit. It was twitchy in the manner of a single seater. This of course was not the case with the BMW which JJ said at the time as having great handling and being relatively easy to drive fast. Mind you what JJ and McNish consider easy or difficult is outside the terms of reference for most of us.

In is generally held that to measure the quality of a victory it is important to measure the quality of the opposition as that will give some scale to the achievement. In 1999 BMW faced one of the strongest line up of factory cars ever seen at the French classic. One of the usual suspects had gone from the top level, Porsche's CEO, Wendelin Wiedeking, preferring to steer the company down a course of money making and away from top line competition. Well we all know how that turned out, don't we?

Another German effort, run on behalf of Team Toyota Motorsports by Toyota Team Europe, would prove to be the fastest car overall at the Pre-Qualifying weekend in May. Outwardly the three Toyota GT-ONEs looked like the cars that had stunned everyone on their debut a year earlier but underneath there were many changes, some made by the team and some dictated by the ACO rulebook. They had a strong roster of drivers that included stars like Martin Brundle, Thierry Boutsen and Allan McNish. With the experience of 1998 under their belts and the blinding speed exhibited they looked like favourites for the top prize.

Another super fast trio came under the banner of Team AMG Mercedes with the CLR. Reigning FIA GT Champions they had much to make up for after the dismal performance of 1998. There was a lot of pressure to perform on the German team whose line up of drivers contained such stars as Bernd Schneider, Nick Heidfeld, Mark Webber and Christophe Bouchut. They had problems during the May weekend with Webber suffering "a suspension failure" and only total commitment by Schneider pitching the car into the top six. This was not the AMG Mercedes way of doing things.

New boys to the 24 Hours of Le Mans were Audi, who split their effort between the open cars run by Team Audi Sport Team Joest (a bit of a mouthful) and closed ones run by Audi Sport UK. The R8R pair were conventional and conservative, much in the way that BMW had been in 1998. They were strongly built but slow compared with the Toyota/Mercedes/BMW opposition.

The closed cars were undoubtedly elegant but rather undercooked, being completed much too late to have any realistic chance of taking on such strong opposition as existed in 1999. For a closer look at the '99 Audi Le Mans' story I refer those who have not been paying attention to this SpeedHunters feature I wrote a while back.

Another very strong entry came from Nissan Motorsport who brought two R391 open prototypes to France as well as recruiting the local boys, Courage, to run one of their V8 twin turbo monsters. The R391s were certainly a first from the Japanese manufacturer, being open and powered by a normally aspirated 5 litre V8, descended from the IRL Infinity powerplant. The cars were light and powerful but like the Audi R8C were late in development and not likely to feature strongly in the results.

The final works entries in the prototype category came from the thundering herd, the Panoz LMP1 pair. The Panoz with its unique layout was always a crowd favourite even if it did deafen all who were near. The Yates tuned 6 litre V8 Ford tuned ceratinly provided enough grunt as David Brabham turned in second quickest time overall during the pre-qualifying weekend in early May.

BMW and Yannick Dalmas had a scare during the May trials when the rear bodywork parted company with the chassis on the approach to Indianapolis, the fastest part of the circuit. The impact with the armco meant that the V12 LMR would take no further part in proceedings that day, so it was fortunate that the time he had just posted would be good enough for qualification.

Following a long tradition BMW had entered an "Art Car" this time with wisdom provided by American conceptual artist, Jenny Holzer. Kristensen scored the sixth best time in it but after the Dalmas incident this car was withdrawn. Meanwhile JJ Lehto showed the potential of the other entry with a fourth best time overall.

So BMW was looking in a good position as the flag dropped for qualifying and practice Wednesday evening. What would the race week bring?

Final part of this story will be posted tomorrow.

-John Brooks

Super nice.

These stories are the best!!!

145 kilo V twizzy, damn!!!

great stuff so far, John! as usual you never fail to impress, and i look forward to Part 3

what does it say on the spoiler and body of the BMW in the last photo?

Awesome, great article John cant wait for part 3.

Zephyr:

I'm just guessing, but I think it's "Lack of speed can be fatal", which would be very fitting, given that it's on the wing

Thanks folks.

@Zephyr.........Jenny Holzer wrote a number of what she described as "truisms" on the car. The rear wing had "lack of charisma can be fatal" , other pithty efforts included "protect me from what I want" and "the unattainable is invariably attractive" most of the hacks in the press room thought it to be utter b#ll#cks, I suspect that we were just jealous that we had not figured such a way of making easy money out a car company. Philistines is what dear Jenny might call us.

Yeah I remember that year and the LeMans race. I should have been learning for my final tests at school but was watching the 24 houres of LeMans. What a great year and what a nice article. Thanks for that one.

It says "Lack of charisma can be fatal"

http://www.autowallpaper.de/Wallpaper/images/BMW/Art-Car/jenny-holzer/Jenny-Holzer-BMW-V12-LMR-.jpg

Another great story John. Thanks for sharing it with us.

When contemplating our lives, personally and professionally, there are areas that all of us prefer not

After the Champagne (or whatever fizzy stuff they use in Monterey) had been washed away, it was a matter

Even for those of us getting on a bit, ten years, a whole decade, is a significant chunk of time. Ten