The legendary Dakar rally. Powering across 9,0000kms of every kind of terrain; up mountains, over never-ending sand dunes, across salt flats, down dried-up (and often, not as dry as expected) river beds. Mud and rain can alternate with choking dust and sand. The temperate can plummet below freezing and soar to over 45 degrees.

For the 2016 race in a couple of weeks time a staggering 354 cars, buggies, trucks, quads and bikes will be thrown at 15 days of fearsome stages, where routes through some sections are kept intentionally vague, putting a premium on accurate navigation. Hidden waypoints test the abilities of the crews to the limits. Stages can be almost 1000km in length. 556 competitors from 60 countries are taking part, including WRC stars Sébastien Loeb and Mikko Hirvonen. Half the entries won’t make it to the finish.

It’s the most extreme automotive event on the planet. So if you’re going to drive it, you don’t just need a tough car – you need a tough driver as well. And if you’re going to attempt the Dakar after less than a year of driving one of the monstrous machines that take part, you’d better be well prepared. British driver Harry Hunt is doing just that; subjecting himself to extreme testing conditions is all part of the necessary prep if he wants to see the finish in Rosario on January 16.

I met up with Harry at St Mary’s University in Twickenham, in the heat chamber of its specialist sports science laboratory. There, Harry’s been putting himself through a punishing regime of tests designed to help not just his body cope with the extreme stresses the Dakar will unleash, but his mind as well. We normally feature a lot about modifying cars, well, here it’s about modifying the driver.

Cars are the basic piece of the Dakar puzzle. Harry will be driving a two-tonne, 320hp MINI ALL4; like most Dakar cars it’s an oversized, extreme silhouette that resembles the car its based on in concept only. It’s built with industrial-strength mechanicals to take the punishment that the Dakar inflicts on it, sporting massive suspension travel and hardcore tyres, and laden with tools and spare parts. But the fragile flesh and bone behind the wheel is a lot more delicate, and even more important to keep running at peak performance.

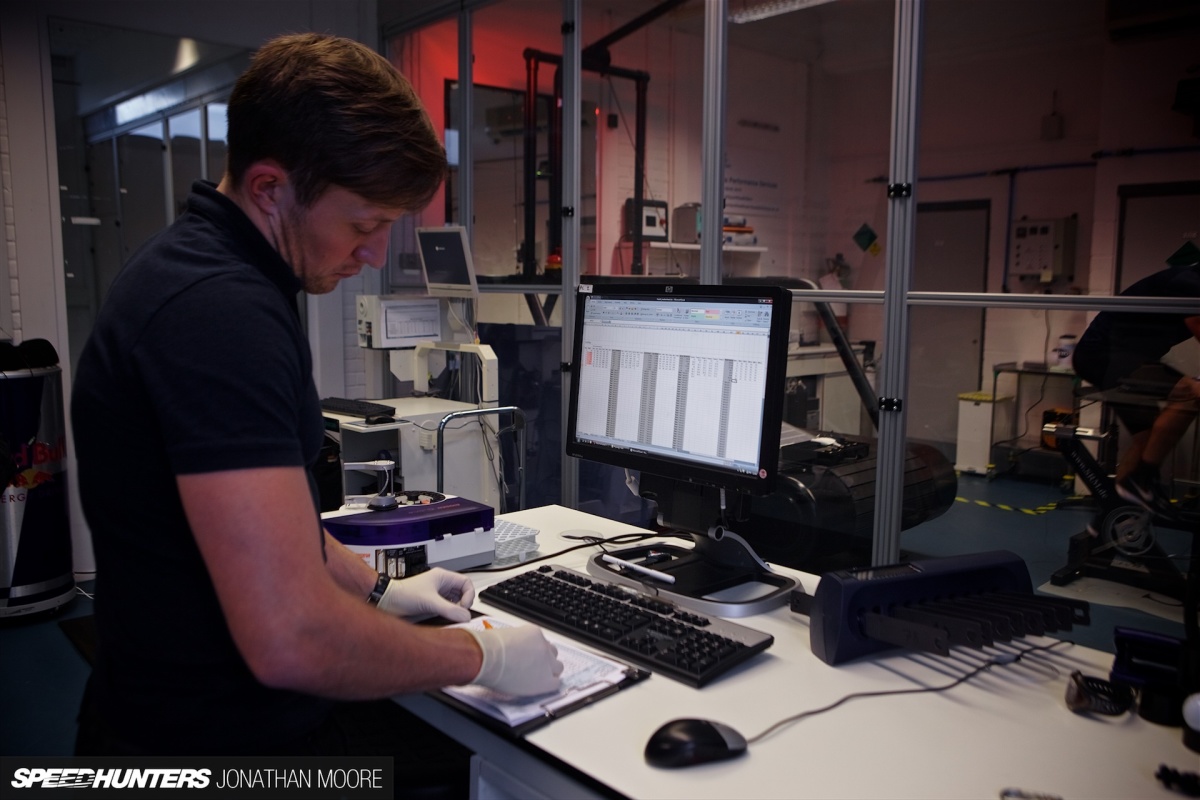

Harry’s session at St Mary’s Human Performance Laboratories was one of many he’s been enduring during the build-up to the big race, which kicks off in Argentina on January 2. Overseeing Harry’s tests was Paul Hough BSc MSc (Hons), lecturer and lead sport and exercise scientist at St Mary’s. He specialises in high intensity interval and resistance programmes to help athletes achieve their highest potential, from ultra marathon runners to Formula 1 drivers.

It’s about getting used to working hard in extreme conditions; knowing how you you’ve physically felt before and knowing it’s not a problem, the mental preparation and being able to focus on the task. The sessions are about stimulating the body’s adaption to heat in general, not necessarily a specific level of heat. In the car it can hit between 40-50 degrees Celcius, but in the training chamber here there’s the added cardiovascular stress from high intensity exercise combined with the high ambient temperature.

One of the big problems can be if you’re thinking more about how uncomfortably hot you are and not on the road ahead. Dakar is not an event you can take likely. Its dangers are greater than just the next sand dune or river crossing, and crews have to be able to deal with its unremitting challenge.

The key point of this training is to encourage, measure and control physiological changes. One of the adaptations you get to training in high temperatures is that it increases blood flow to the skin, which allows you to dissipate more heat more effectively. Hydration levels are associated and critical; you want to minimise total liquid loss, whilst matching that with intake of fluids to keep the body thermally regulated. Otherwise the heart has to work faster, which can affect the mind as much as the body.

The university’s heat chamber can also simulate the effects of up to 2,000m altitude, which can be another major psychological factor when driving. Harry’s had one session at that simulated 2,000m in 35 degree ambient heat. When he said that one was “tough”, the look on his face clearly showed it was an understatement…

With Harry kitted up and fitted with a heart monitor, Paul started by taking a baseline body mass index and various other measurements before hooking Harry up to a temperature sensor inserted into his left ear canal. At regular 10-minute intervals readings would be taken, both physically and verbally.

Blood samples would be used to measure blood lactate and glucose levels, the electronic thermometer recording body temperature whilst Paul noted the ambient, and then Harry would also be asked to give his perceived level of exertion and temperature against a given scale. The psychological reaction to the exercise is just as important as the physical goals.

As Harry began pushing on the pedals for the beginning of his 50-minute session the temperature in the lab was already edging toward the mid 30 degrees Celsius. As if the main blowers weren’t making the room hot enough, floor heaters blasted out more heat at ground level. I’d have the chance of ducking out of the chamber if I got too hot – that wasn’t an option for Harry.

Pushing To The Max

Harry’s rise in rallying has been pretty meteoric. From a passion for rallying in his late teens, he only started competing in 2009 at the age of 21, following some testing in Group N machinery. In 2011 and 2012 he blitzed every series he entered, winning the IRC 2WD Championship two years running as well as the JWRC Rookie Cup and PWRC 2WD Championship. After a year break he decided to make the massive change of heading into endurance rallying, with Dakar the target. It’s like going from sprint training to a marathon – the consistency and concentration required is staggering.

The general fitness level required is apparently not that much higher than for competing in the IRC or WRC (i.e. high), where stages are short, sharp shocks; 40 minutes or so of total concentration. With the Dakar you can get long sections of flat or something like a river bed that you can charge along for many kilometres, allowing time to grab a drink or something to eat. But Dakar throws in insane length, plus additional factors like incredible heat variations and high altitudes.

Harry’s basic fitness regime is what you’d expect: running, rowing, some weights and playing football with friends – although the latter was coming to an end as Dakar got nearer. An errant tackle couldn’t get in the way of something this big…

His co-driver is Dakar veteran Andreas Schulz, who has competed in the event 22 times and been on the winning crew twice. What he doesn’t know about rally raid driving isn’t worth knowing, and his advice has helped shortcut Harry’s steep learning curve. Andy might be 62, but he’s seen it all – which is also why he leaves the hardcore training to Harry!

At the first interval check all seemed pretty easy, with Harry’s Perceived Exertion at 10 (light) and a Thermal Sensation at 3.5 – halfway between cool and comfortable.

Why all this is necessary, it’s made even more clear when you talk through the realities of competing in a normal rally raid, let alone the Dakar. Stages are hundreds of kilometres long, and although the cars do have air conditioning when the temperature is soaring outside, the system is just pushing hot air around.

At the Abu Dhabi round of the FIA Cross Country Rally World Cup at the beginning of 2015, Harry had a harsh introduction to the sport: the fan broke and the average temperature in the cabin hit 52.5 degrees. It was the hottest he’d ever been in his life outside the car, let alone whilst driving it. Nerves set in, causing mistakes, particularly on the massive dunes they faced. Cutting the ridges, sand was being thrown up and over the car, which was then getting into Harry’s face and helmet.

It’s also easy to forget the liaisons; the regular road mileage that has to be racked up travelling between the competitive stages. You can complete a six-hour stage after four hours of travelling, only to face hundreds of kilometres of driving to go to get back to base camp. Days are never short, but energy can be. Fluctuating heat, tiredness of muscles and brain; Abu Dhabi was a five-day baptism of fire, though Harry still managed third place overall on his debut and learned valuable lessons. Dakar is three times longer and many multiples more challenging, hence the decision to take on this kind of extracurricular training.

At the second interval, 20 minutes in, and ratings of 11 and 4.5 revealed that Harry had finally noticed it’s almost warm in the chamber. The conversation started to come between regular breaths as the temperature climbed and the relentless cadence began to dig into Harry’s muscles.

Harry’s competed in just four events leading up to the 2016 Dakar. After his Abu Dhabi debut podium, he then raced in Qatar, the Baja Spain and then Morocco, gaining experience at each step. Building up the relationship with Andy has been massively important, as it has with the German X-Raid team that are supporting the car.

He’s now getting settled into a post stage routine. Once back at the overnight bivouac he’ll usually have a massage session with the team physio and take on board plenty of electrolyte-laden energy drinks. It’s about relaxing, eating early and well and then getting to bed as soon as possible to try and grab seven hours or so of sleep.

Even though he was pounding away on the bike and dripping sweat as he said it, Harry reckons the drivers have it easiest – relatively. The navigators have to prep for the next day’s stage as soon as they hit the camp; that means sorting out the road book for hundreds of kilometres of stages, using highlighters to mark danger spots, speeds and distances, going over the route three times. It can take three or four hours, which means they get little sleep. It’s even worse for the mechanics and team crew, travelling to the next bivouac whilst the cars are on the stages and then working overnight to fix the inevitable damage that’s been done to them.

Never Underestimate The Challenge

Half an hour in. It was now officially warm, with reports of 12 Exertion and 5 on the Thermal Sensation scale. The software on the bike automatically managed the resistance, so that Harry had a constant power output to match. Pedal faster and there’s less resistance, slower and it’s tougher, but at each increment the power to be achieved goes up a level.

Liquid intake is critical when in the car and has to be learned. Harry and Andy each have three-litre capacity drinking systems, contained in insulated carbon cylinders, plus a reserve; but in high temperatures it doesn’t stay cold for long and the warmer it gets, the worse it tastes. But at least it will stop them passing out…

Their on-board drinks are laden with electrolytes and salt; after the Abu Dhabi race was over, Harry’s black suit and belts were almost white from the amount of salt he’d lost during the event, reinforcing that it’s not just about pure water. And if you have a call of nature? You hold out if possible, although some drivers do wear the adult equivalent of nappies to take care of any unavoidable issues whilst on the move for an entire day.

As if dealing with driving the car wasn’t enough, Dakar crews are also expected to have to carry out running repairs to any damage that they incur. Often the cars are literally in the middle of nowhere, and can be stranded in endless dunes with no kind of communications. They carry satellite phones, but getting a signal isn’t easy – and loses time. Harry’s MINI is a spaceframe chassis with integral hydraulic jacks; the rear is stuffed with spades, shovels and other practical tools, alongside the more expected spare tyres and components like driveshafts, bottom arms, hubs, sensors and diffs.

They have to learn about the whole car; in fact, Harry had recently returned from a week at X-Raid’s Frankfurt base practising changing parts and effecting repairs. Different size belts can be used to bypass failed systems like air con, pumps and power steering; whatever it takes to get the car to the finish and into the hands of the waiting crew. They carry a full set of laminated reference cards in the cockpit to help them out.

The ambient temperature was up to 37 degrees now, seriously hot even for me taking photographs, let alone for Harry on the bike. By this time the ache of muscles and short breath must have been making every minute seem longer.

As the final 10 minutes ticked by, conversation ebbed away as the intensity and temperature hit their peaks. 16 and 6.5: edging towards very hard and very hot. Out of courtesy we let Harry pound away at the final run – there’s only so long you can sit about watching someone else slog their guts out…

The seconds slid by as the countdown dragged to its conclusion. Finally the session was over and Harry could sit back, exhausted, and start his recovery: he’d lost 1.3kg, which means he was dehydrated by 0.5% and had a sweat rate of 1.5 litres/hour. This is on the lower end of the range of typical fluid loss during this type of heat session, as he was drinking effectively during the session (850ml throughout) . Let alone the pain of the exertion, it can cause a massive headache that just won’t go away for ages. However, the adrenalin high goes some way to compensate.

After the session Paul analysed the averages for each stage, looking for responses between sessions to monitor over time. Data sheets are used for comparison from previous sessions, with average power output and lactate values. Ideally he wants the power output to creep up but lactate levels to remain stable, which would mean a higher power output with the same heart rate – a measurable physiological response that Harry is adapting to working in heat. It’s the same with the perceptual responses, wanting the reported values to be closer to the measured temperatures.

The training seems to be working well; Harry’s figures were going in the right direction, as well as more instinctive things like when to take on board fluid. Knowing intuitively when you really need liquid compared to just wanting it can make all the difference. Even being distracted with conversation during the session only had a minimal impact. I like to think I was almost helping his training…

More sessions would follow my visit. The intensity will be maintained right up until the moment Harry flies out to South America just before Christmas for a brief bit of R&R with the family before going up with the MINI team in Buenos Aires. His focus is all on Dakar, but there will be another half dozen or so events for him next year before the next chance to take on this monster event. Harry’s well aware that this is a learning year – just completing it will be a victory. Every kilometre will be a learning experience and a massive challenge, but one made that little bit easier by putting in this kind of hardcore training.

Jonathan Moore

Instagram: speedhunters_jonathan

jonathan@speedhunters.com

Great article! Didnt know drivers had to go through so many physical tests like that, very interesting. Great shots as well, my favorite is the side shot of the mini tearing through dirt. Its beautiful

The dakar doesn't finish on Bolivia. The finish line is in Argentina, also the start line. They start in Buenos Aires, go up to Bolivia and back to Argentina to Rosario city.

Everything about this is so freaking cool! Excellent work.

Cool article, thanks for the insight.

Wow

It is crazy that people do such things. They dont try to go as fast as they can, its all about surviving the challenge.

I can only imagine how hard (and hot) it must be driving the Dakar Rally on a bike.

roadduck313 Humor!!! Arf, arf, arf!

Amazing article , sooo cool to see other side of pro racing .

Interesting article!

Speedhunters thanks for sharing Speedhunters, have a great Saturday (insight by http://commun.it)

(insight by http://commun.it)

roadduck313 Surely it must be twice as brutal on a bike

Great article! We always forget to tune the driver as well

As a cycling nerd I find it amusing he uses brake levers on his indoor bike.