A visit to the Goodwood Festival Of Speed means you’ll be awash with memories: it’s like stuffing everything that’s great about a century of the automobile into four days, giving you first-hand flashback memories of series that had their glory periods when you weren’t even born and taking you all around the world to every great track, road and rally stage a car has ever been driven on. Goodwood doesn’t just provide displays of moving metal: it provides context – and something it’s perfected that idea with is rallying.

In the Festival’s sprawling manufacturer compounds and main paddocks were plenty of mini temples to the art of the gravel destroyer, the mud thumper and the tree skimmer – and often in unexpected places, like the short wheelbase quattro that rested on the Michelin stand.

Rally cars get to ascend the Goodwood hill in their own class of course. The Ultimate Rally Cars batch included some of the most famous machinery imaginable: more fearsome Group B cars, the cream of the modern era WRC and several Pikes Peak cloud busters besides.

But much as this collection was exciting to see, whether powering up the hill or sheltering under the paddock awnings, there was something not quite right. There was something about it all. Something missing.

Oh yes. You need to take the same model and apply it to a real rally stage. You need bent panels. Scuffed edges. Dirt.

What we needed was attitude at altitude. I needed to go up the hill. And then I needed to see cars going up fast, and coming down hard.

Where we were going, we wouldn’t need roads.

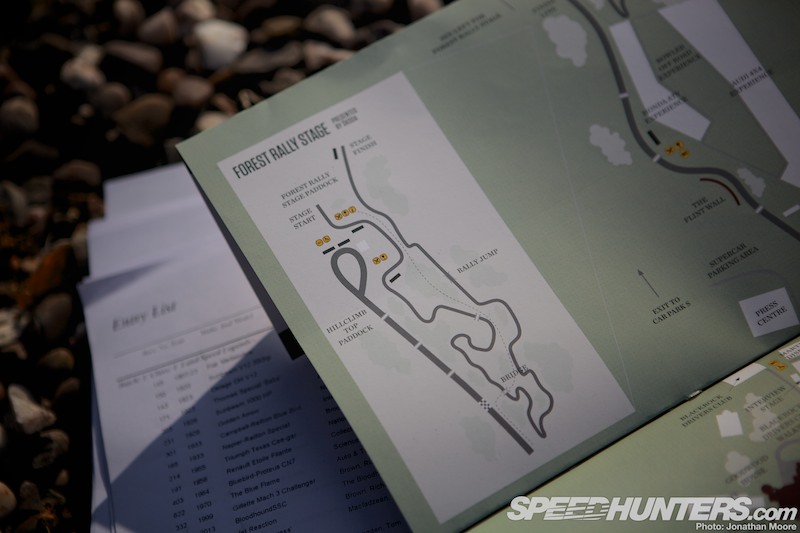

Planet dust awaited. Goodwood’s Forest Rally Stage, tucked up in the woods at the top of the hillclimb. Home to rally car heaven, where the wild side could be properly unleashed by the drivers and therefore properly appreciated by the fans.

The long trek up to the Forest Rally Stage meant entering a different world from the hustle and bustle of the main Festival Of Speed area, exiting the crowded green grass banks and entering the claustrophobic forest.

There’s always a hush that descends as people make the transition from open sky to the shelter of the forest canopy (though maybe that’s also because it’s so far to walk and everyone’s tired!). The only sound you could hear was the unnatural pop and bang of an epic rally machine hammering by just feet away, wheels barely in contact with the ground, the car dancing along the loose surface.

The creation of the stage, christened in 2005, was a true stroke of genius. The original layout was designed by WRC legend Hannu Mikkola, and has been subtly refined over the years.

Dug out of the forest, the chalky surface is easily rutted as the stage goes live, and most of the course involves threading a high powered needle through a combination of earth banks and less than forgiving trees.

One exception is the wide open jump near the end of the stage… I could stand there all day as car after car got air.

Short it may be, but the Forest Rally Stage is no stroll in the park. It’s a gravel and dirt-filled car destroyer, a potential car-compacter.

Like seeing priceless sports cars being raced in anger, there’s just something unreal about seeing proper rally cars out on a stage. Going rallying means your car will be damaged in some way every time it goes out.

Even completing a run successfully (ie, not hitting a bank or, god forbid, something more solid) will still mean that the car will be peppered with gravel hits.

It’s not a place for people who like pristine cars. Maybe that’s why I like it so much.

This might not be a 30km special stage taking 15 minutes through a Finnish forest, but it’s not a bad approximation. The Forest Rally Stage still provides two and half minutes of constant action. Straights? Not really. And rally cars don’t really go straight anyway!

This year the stage has been further modified and lengthened by a quarter mile, with the biggest alteration at the start and finish.

Previously the cars would take off on gravel, around the left-hander at the end of the new launch straight, but now a lovely line of tarmac has been laid at the beginning and end of the course.

Much as the sight of a four-wheel drive maelstrom of dust was impressive, it did hinder any chance of actually seeing the cars take off, so this small section of tarmac provides a more tractable surface to start on, and the chance for some glorious rubber burning before the tyre shredding begins.

The rally boys and girls have their own dedicated paddock set up on the crest of the hill above the startline, a much more airy and less crowded affair than the lower paddocks for the hillclimbers.

But the ethos was the same: the cars sit under their awnings, with maybe a toolkit and a spare wheel or two to hand (although a couple of teams did have support trucks nearby), and you can take all the time you want to examine the cars and talk to the drivers.

When their slot came up, the driver would nose their way through the crowd to line up. Five classes ran in 2013, with examples of cars from all 11 manufacturers that have won titles over the last four decades – the WRC was yet another thing to be celebrating a major anniversary this year – and countless other models as well.

Several of the WRC cars and drivers based at the bottom of the hill and taking part in more sedate ascents of the hillclimb would also send their cars up to the Forest Rally Stage. The great news for us was that the list included Citroën World Rally Team star Mikko Hirvonen. Seeing a driver with his level of commitment, displaying balls-out aggression from the moment the timer went green, was like experiencing the stage on a completely different level.

You would hear the DS3 coming: the exhaust popping, the turbo whining and gravel shotgunning the trees in its wake. You’d prepare… and then suddenly the car would leap into sight, jinking about as Hirvonen approached right on the limit.

Miles before the corner he’d already be sideways; Hirvonen was thinking in a different time zone, corners ahead of what the onlookers could keep up with.

Then in the blink of an eye he’d be gone, disappearing in a cloud of dust as we were showered in his ejected gravel. The Citroën would once again be the distant sound of fury moving on to shatter another piece of the forest. This is what the WRC is about. This is what they should be selling us.

I feel terribly guilty that after every Festival Of Speed I come home revelling in dust-fuelled memories of rally nirvana that are never followed up on. I do so hope that the WRC can pull itself together and find a way of promoting the series to the level it deserves. We all need more rallying in our lives.

Being covered in dust from the Goodwood stage feels almost like a badge of honour; nuclear fallout from the power of the cars that pass by that coats every surface…

… and turns nature’s green to grey. And all my equipment too – which needs a damn good clean before the Spa 24 Hours. Though the almost guaranteed rain will maybe do that job for me…

Anyway. Watching from the side of the stage is all very well (though when Hirvonen was involved, also a gravel-strewn experience)…

… but it doesn’t get much better than seeing things through the windscreen. I was privileged to be offered a passenger ride in the Skoda Fabia S2000 with rising star Robert Barrable at the wheel. I was in for an unforgettable experience.

From the moment I was suited up, helmet on and strapped in, I felt a second or two behind everything that was happening – even before the timer ticked down to our start.

Plugged into the intercom, the majority of engine noise came through my earphones, which made for an almost out-of-body feeling to it all. As ever with a proper racing car driven by a professional, my reaction as the Skoda ate up the hundred metres to the initial left-hander was a repeated prayer that he would at some stage brake, to abate the enormous speed we were building up.

My prayers were unanswered until what seemed far too late; with a clip of e-brake, Robert threw the car in sideways and it miraculously glided over the deep ruts like they weren’t there. I had no chance of keeping up with this.

Sliding through the loose, long right that followed, we breached the forest shadow and disappeared under the trees.

As my eyes adjusted, my nerves refused to. The Skoda was travelling along the gently curving opening section at a speed I just couldn’t process; the small banks at either side now seemed like cliffs just inches away from the side of the car.

It felt like there was just constant acceleration. Most corners didn’t seem to exist, or happened so quickly that they had been and gone before I’d bought a ticket for the entry.

Robert phased the Fabia through each curve with no respite. When I’ve had passenger rides in sports cars, I typically spend as much time watching the driver’s hands and feet as I do the track, but there was no chance here. Nothing happened at a slow enough speed to come to terms with; gear changes were seamless, the e-brake seemed to be pulled miles before a corner, the Skoda magically rotating before each apex and already prepped for the corner to come.

Trees flashed by at a frightening rate. Only one corner had given me a chance to just about get back in step with Robert’s driving – the long left-hander hairpin about a third of the way in, which had seemed slow-motion in comparison to the previous 45 seconds – but then we were back to light speed and I had no chance.

The previous day I’d enjoyed a 10 minute break at the bottom end of the stage, where the course broke out into the daylight for its only other piece of asphalt at the hairpin. Cars arrived cloaked in dust from the stage, so I knew the solid surface didn’t necessarily mean grip.

And that’s exactly what everyone wanted: especially the marshal’s post, who kept a running tally of drift scores through the weekend. The winner? Hirvonen was scoring top points every time he came through, though Robert was right up there. I wondered if the guys had spotted my disbelieving face as Robert slow-motioned the Fabia round the halfway point.

Then we were straight back up to fast-forward, with just a chance for another ‘please, please brake’ moment as the sharp right-left chicane approached. By this point I knew what was coming up in a couple of corners.

The knowledge of the jump filled me with a combination of joy and nervousness. As with the hairpins, a kind of movie bullet-time kicked in as I felt us hit the crest…

There was a momentary feeling of weightlessness as the Fabia hung in the air…

As we came back down to earth, I had the sensation of one of those multi-angle camera rotations around me…

… taking in every angle…

… before I felt the front wheels touch down.

Time accelerated back to a blur, as did Robert. I don’t think I’d actually taken a breath in two minutes; I had to remind myself to take in air. We snapped out of the forest and back into the sunlight for a flat-out left-right kink, throttle still to the floor even as we passed the line, before Robert stood on the brake and the normal passage of time returned. I was alive. And I wanted to go again…

So how did it look from my point of view? Like this. I’m very glad the balaclava covered my mouth, otherwise lip-readers out there might be able to get me in trouble…

Jonathan Moore

Instagram: speedhunters_jonathan

jonathan@speedhunters.com

The 2013 Goodwood Festival Of Speed on Speedhunters

More Goodwood stories on Speedhunters