To kick off our supercar mini theme, let’s go back to the origins of the genre and the decade where the first generation of supercars emerged: the 1970s. It might be the period that time wants to forget in terms of fashion, but it’s the place to go for the exotics that set the scene for pretty much everything we have today.

Right from the birth of the automobile there had always been cars that pushed the limits. If you take the idea that a supercar is one that transcends the norm in terms of speed, performance and their relevance to regular traffic regulations, then you could argue that even the earliest cars deserve that epithet. But the 1960s had led to an explosion of fast cars hitting the roads and the emergence of a new breed of performance brands, as highway networks spread their tendrils further across Europe and America, the global economy picked up and the car became the de facto form of transport. Racing had again gripped the public imagination, but the highest performance cars were mostly limited to the track.

Towards the end of the decade things had begun to change though, with cars like the Lamborghini Miura and Ford GT40 (cars with very different origins) launched. The scene was set for the glorious supercar revolution of the ’70s.

The ’70s was when a new breed of cars, distinct from anything else on the road, began to emerge. Rather than one-offs or race-derived specials that had been seen before, these were proper production cars aimed at a new wealthy and aspirational section of the population. It was a new market that everyone wanted a slice of. Extreme design, extreme performance – extreme exposure.

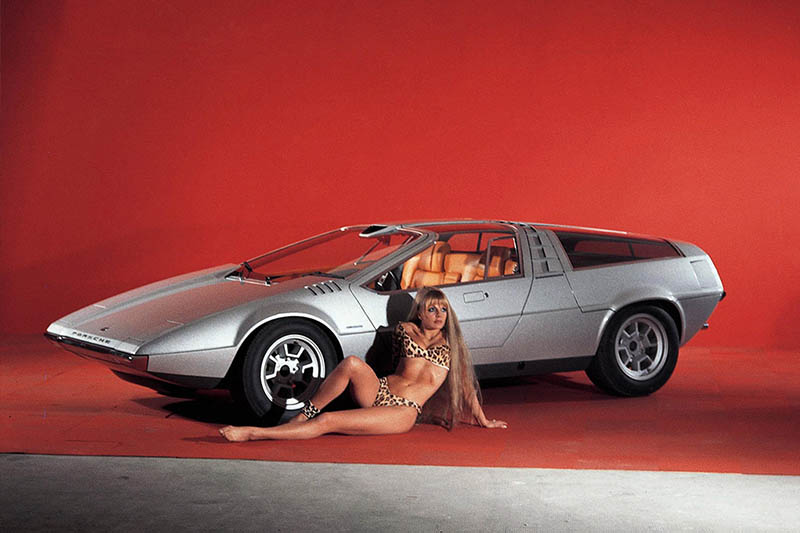

There was a definable change in the design language as the ’70s arrived, where hand-crafted curves and old-school organic style of the ’60s gave way to a chiselled, machine-code look of hard lines and brute force. Softness be damned: make it sharp, make it look anti-nature. These are the halo cars that looked, sounded and performed like nothing else on the road; the pin-ups of a generation. And most would still happily grace the walls of any car fan today – even the ones that were just concepts, like the 1970 Porsche Tapiro.

But what actually defines a supercar? What makes us look at a car and automatically place it on a pedestal above others, and why was it the ’70s that saw that automotive evolution? It’s not necessarily just cost – though an astronomical price tag did usually come hand in hand. It’s not always about being derived from a racing car – in fact, often the racing car came about after the road-going version at the beginning of the decade. But limited edition? Almost certainly. Mid-mounted engines and two seats? Pretty much always. Exclusive, edgy, dedicated driving machines? Definitely.

Like fine art, supercars transcend their genre – they are a level above grand tourers or tuned sportscars and they take the whole driving and ownership experience to a new level. But that the genre survived the ’70s at all is a testament to their popularity. The oil crises and regulations of mid-decade almost killed off any kind of performance car, but these groundbreaking cars pay testament to the start of something unstoppable.

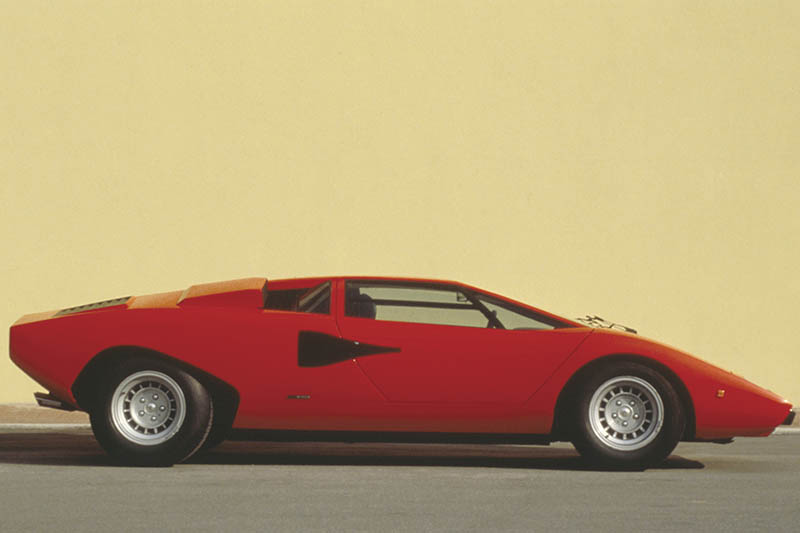

Lamborghini Countach

1974

Lamborghini’s Miura of the late ’60s is still rightly regarded as one of the most beautiful performance cars ever designed. That car had been a revolution in many ways, and is seen as the father of the mid-engined supercar genre. But in 1974 the Countach took the mould, smashed it and remade it with knives and hammers.

Gone were soft, flowing lines; in came the futuristic spaceship wedge that looked like nothing anyone had seen before on an actual production car. Concepts had dared to explore this territory, but no one had really carried the extreme style through to the road. The cockpit was mounted towards the front of the car to allow better positioning of the huge V12 behind, the doors used a space-age scissor movement and the overall shape was incredibly wide and low, covered in racing-style NACA ducts and intakes. It’s strange to think that the Miura and Countach shared one designer: Bertone’s Marcello Gandini.

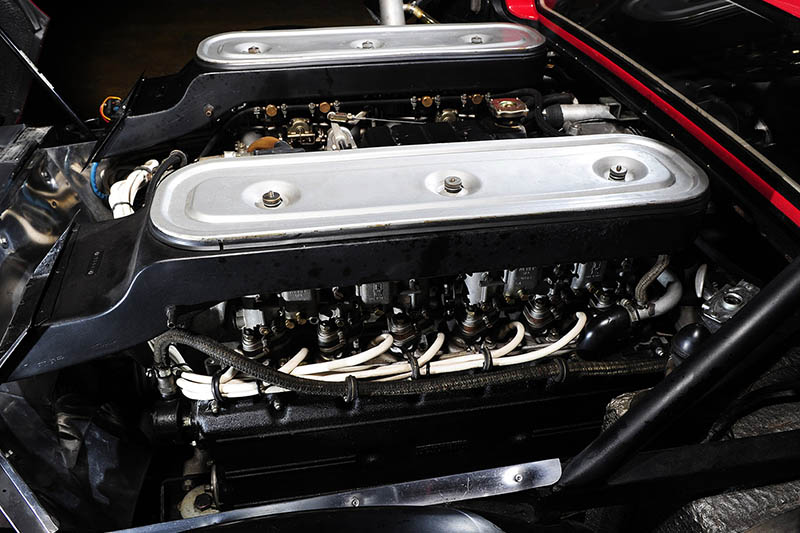

The LP400’s 174mph top speed came courtesy of a 3.9-litre, mid-mounted banshee V12 producing 375hp, fitted transversely and in reverse to improve weight distribution and to tick every ‘let’s be different’ box. Underneath the aluminium skin was just as cutting edge, with a spaceframe chassis and fibreglass underbody.

The LP400S was introduced in 1978, and although the engine actually slightly lost power in this version the whole car muscled up, with extended wheel arches to enclose much wider rubber and the option of the iconic flying-V rear wing. It actually slowed the car down, but still – who wouldn’t want the wing? Most customers went for it.

The car is surprisingly compact in the flesh, and with a weight of just 1,000kg (2,200lb) you can see why it went as fast as it looked. Trying to see anything behind you was pointless. The rear view mirror just showed a big engine, and the side mirrors flapped around aimlessly. But then, who or what was ever possibly going to be coming up to overtake a Countach? Who would be reckless enough?! You reverse parked one by opening the door and sitting on the sill. Or you just went nose-first all the time…

The Countach kept on coming: it was in production for 16 years, and was simply the poster child for the new supercar generation – quite literally. When teenagers (and adults) of the time weren’t buying posters of tennis players scratching their posteriors, they were sticking up a big image of a Countach on the wall. Even now people are still transfixed by the car, and it’s not surprising. The Countach is still an utterly captivating object.

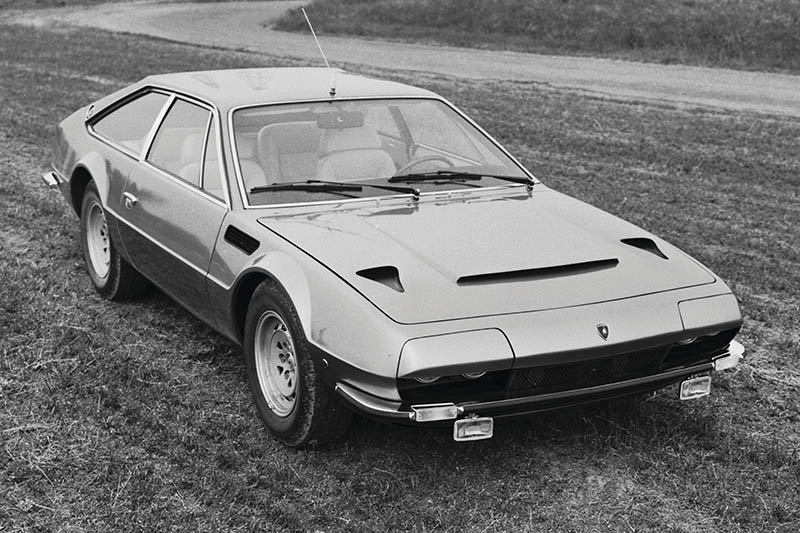

Lamborghini Jarama

1970

The Countach had been preceded by the Jarama (a redesigned Islero coupé, made necessary by US standards criteria) and starkly illustrates where supercars had evolved from and the enormous impact of the Countach. It’s a quirky car to include in this company, but demonstrates that tipping point between the old world and the new supercar horizon. The FR Jarama mounted a big 3.9-litre V12 up front, which made for a handy amount of power: 350hp from the first version, and then 365hp from the S version made for the final two years of production.

The aerodynamic body was designed by Gandini at Bertone again, and just 328 were built. Influences from the Jarama can be seen in Japanese cars of the following decade, particularly in the rear three-quarter shaping.

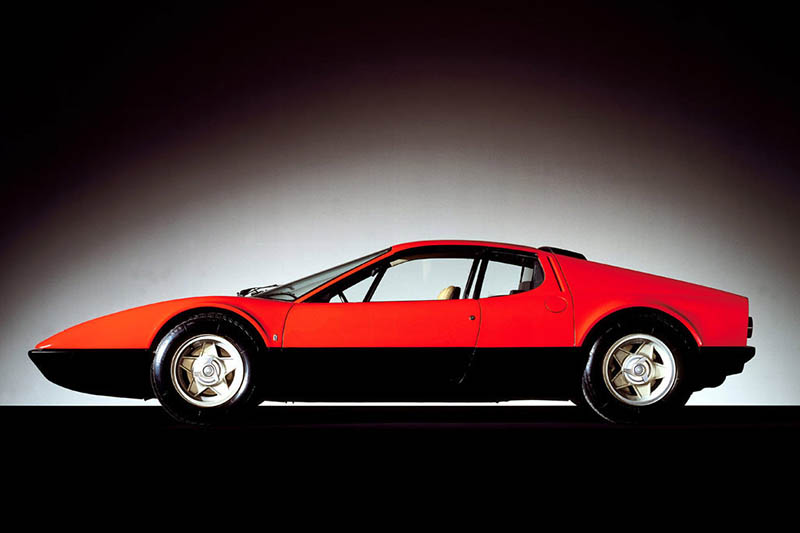

Ferrari 365 GT4 Berlinetta Boxer

1973

Ferrari and Porsche had been locked in a battle for supremacy both on the track and on the road for decades. They both had their own singular approaches – Porsche’s unswerving dedication to small-step evolution in both the shape and concept of the RR 911 (which would meant they wouldn’t join the supercar club until the following decade) and Ferrari’s more boisterous, Latin emotional attachment to the colour red and inserting screaming V12s wherever possible, sensible or not.

The Ferrari 365 GT4 Berlinetta Boxer was designed by styling house Pininfarina, and was first shown at the Turin Motor Show in 1971: the car finally went on sale in limited numbers in 1973 – fewer than 400 were crafted. Pop-up headlights and wedge-shapes were all the rage, allowing for more aero-friendly designs, but that didn’t stop the 365 GT4 BB from being a beautiful car. It might have screamed performance, but it also also tastefully exhibited classically Ferrari sculptural curves to counter that obligatory raked ’70s wedge. Triple rear lights help distinguish it from its similar but less rare descendants.

The concept for the howling 4.4-litre flat 12 was taken from the team’s Formula 1 programme, and sung away from its longitudinal, mid-mounted position – a first for Ferrari, and something that had taken a while for the engineering department at Maranello to convince ‘il Commendatore’, company founder Enzo Ferrari, to accept. Being roundly beaten in racing by mid-mounted opposition helped swing that one.

Faster even than the Countach (this was one car that Lambo drivers had to look out for), it sprinted to 60mph in 5.4 seconds, and had a wafer-thin 1mph top speed differential over the Countach. It also set the template for a whole host of Ferrari supercars to come, starting with its own descendent, the fearsome 512 BB. A 4.9-litre flat 12 now pushed the car to almost 190mph – that magical 200mph mark was getting closer and closer…

De Tomaso Pantera

1971

The Pantera was the upstart in the new supercar era, built by specialist firm De Tomaso in Modena, that area of Italy awash with niche sportscar atelier. Its shaping wasn’t a million miles away from what would come with the Countach a couple of years later, but was more subtle in the execution of its wedge design, carrying over some softer, more ’60s curves. In a way the original design seems like it could sit halfway in design terms between the svelte style of the Miura and the brute angularity of the Countach, just as it does in age.

The Pantera was aimed squarely across the Atlantic, and came full of trick tech that was de rigeur in the States but rare in Europe, like electric windows and air conditioning. That US link was further strengthened by a De Tomaso’s deal with Ford, both for the motivation for the Pantera and dealership forecourt space. The former was the reason for the very different sound to the Pantera compared to the majority of Italian exotica: a deep rumbling V8 rather than barking V6 or howling V12. The initial Panteras used big-on-torque Ford 351ci 5.8-litre V8s mounted amidships and a ZF transaxle, with disk brakes and rack and pinion steering also part of the spec.

Poor build quality meant the first cars sold badly, and the performance wasn’t groundbreaking for such an exotic car. Still, particularly in the States, driving a GTS certainly made you stand out from the crowd. A new V8 was sourced and the cars were constantly played with over the – incredibly – 20 years of the Pantera’s production.

The original lines of the Pantera, which brought together Italian coachbuilder curves and bluff US muscle car presence, gradually became more extreme as the ’80s arrived, hulking-out with wheelarch extensions, wider bodywork and a Countach-like rear wing. All this followed the breakdown of the deal with Ford, after which the cars became largely hand built in far smaller numbers, with hundreds every year rather than the thousands of the Pantera’s glorious beginnings.

Maserati Bora

1971

French firm Citroën had taken a controlling interest in the Italian exotic brand back in 1968, and were quick off the blocks in designing a new-age two-seater supercar. The Bora was shown off at Geneva in 1971, with cars in customers’ hands by the end of that year. Designed by Giugiaro, the Bora used a monocoque chassis with subframes front and rear; suspension was modern double wishbones and coils all round in combination with anti-roll bars.

The shape of the Bora combined that ubiquitous wedge with something far more refined: a large, grand tourer-style rear deck that used plenty of glass to show off both the engine and accentuate the general fastback beauty of the tail. Citroën’s influence was clear in the underlying technology: hydraulics controlled the vented disk brakes, as well as the pedal box, driver’s seat and pop-up headlights. It’s a gorgeous car which oozes style.

The Bora was a solid performer rather than a screamer and Maserati’s classic all-aluminium V8 was initially bored out to 4.7-litres, making for a handy 310hp. Like the Pantera it used a ZF transaxle. Top speed was 170mph, though the 0-60mph was a relatively relaxed 6.5 seconds. There’s another Pantera link: Maserati were sold on again in 1975, and were bought by De Tomaso (of all people). With the Pantera still in production the Bora was naturally sidelined, and just 524 had been built by the time production ceased in 1978.

Aston Martin V8 Vantage

1977

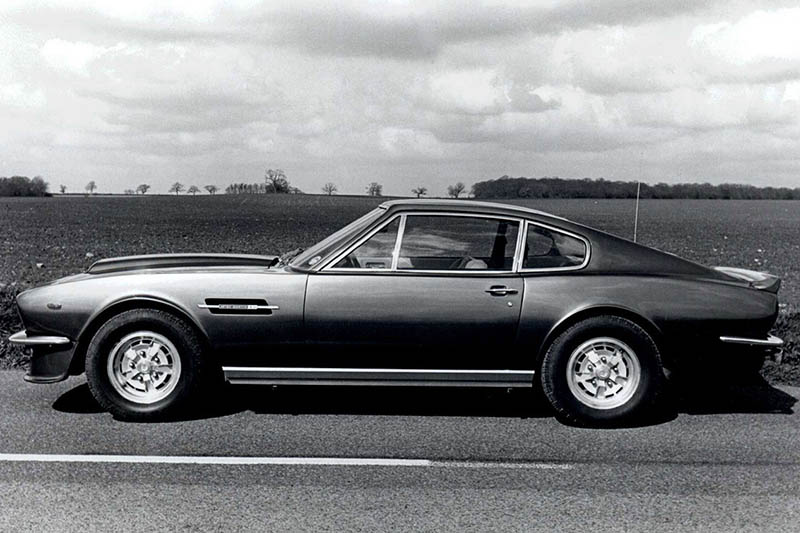

Who says the Brits couldn’t do supercars? Whilst the Germans and Italians slugged it out, Aston Martin came in from the leftfield in 1977 with something that looked like it would be more at home howling down an interstate in America rather than gliding gracefully through London’s classier streets: the V8 Vantage.

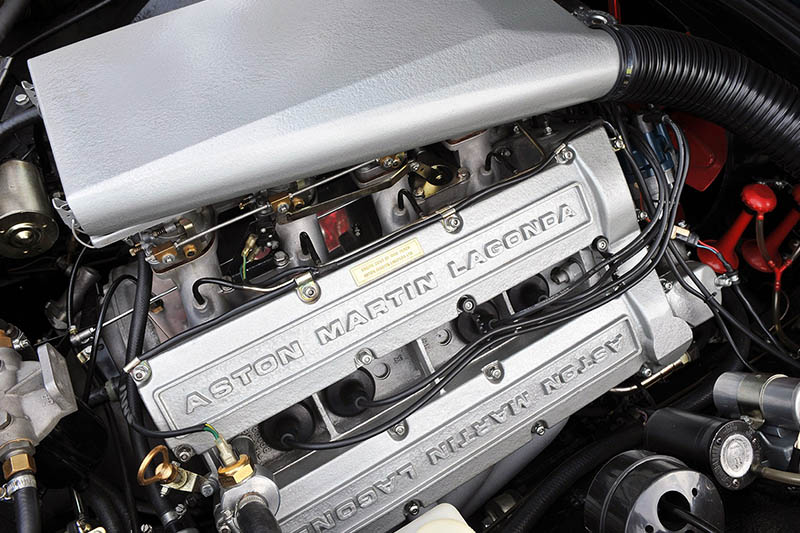

US muscle car influence wasn’t just skin-deep: Camaro design cues were clear front and rear, but under the long hood was a thug of a V8: a 5.3-litre block for this gentleman’s brawler.

Big it might have been, but the Vantage hustled along at a fine crack – definitely supercar territory. It was as fast to 60mph as the Porsche Turbo, and could go toe-to-toe with the best around all the way to 170mph, with vented disks helping bring everything to a halt should the need arise.

I still think this is a surprising car to have come from Aston, following on from the shapely DB6 but eschewing the modernist look of so many other cars here. Vive la difference!

Lotus Esprit

1976

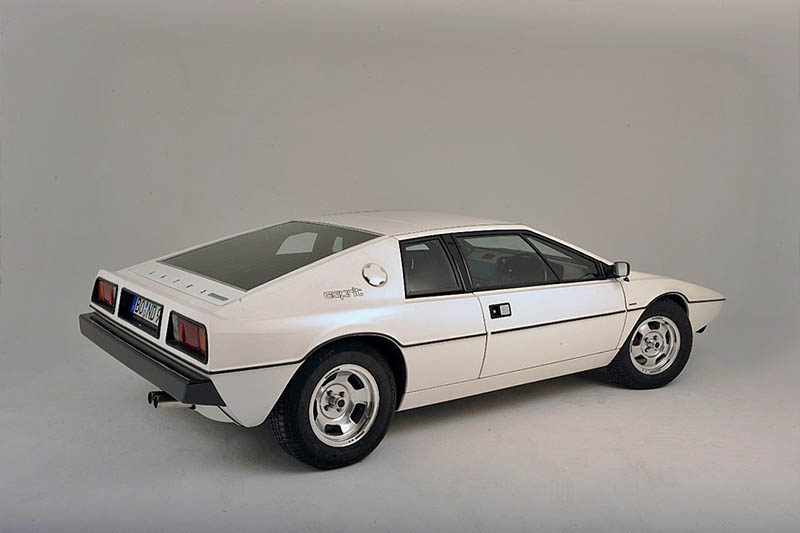

From blunt force trauma back to Italian styling sensibilities for our second British supercar of the ’70s: the Lotus Esprit. A Giugiaro design, the compact 1975 Series 1 Esprit continued the ’70s propensity for wedge shapes, combining striking looks with Lotus’ traditional target of light weight. It was devolved from the M70 concept that Lotus had showed off at the Turin Motor Show in 1972 – one of the first wave of angular concepts.

Like the Bora, the S1 was admittedly no performance beast – this was a handling car rather than something you went after outright numbers in. The weight of the steel backbone chassis Esprit was under 1,000kg (2,200lb), but the longitudinal, mid-mounted two-litre engine only produced 160hp.

Less than 900 S1 Esprit rolled off the Lotus lines in the first three years of production before the introduction of the Series 2 in 1978 when small improvements were made on both performance an aesthetic fronts. Aerodynamic efficiency was further improved with changes to the integrated front spoiler, and speed was marginally up to 138mph.

One of the most recognisable road-going S2s was the special edition car made to commemorate Lotus’ multiple Formula 1 World Championships. The JPS used the iconic black and gold livery of the F1 cars, and added gold-coloured alloys and a racing steering wheel.

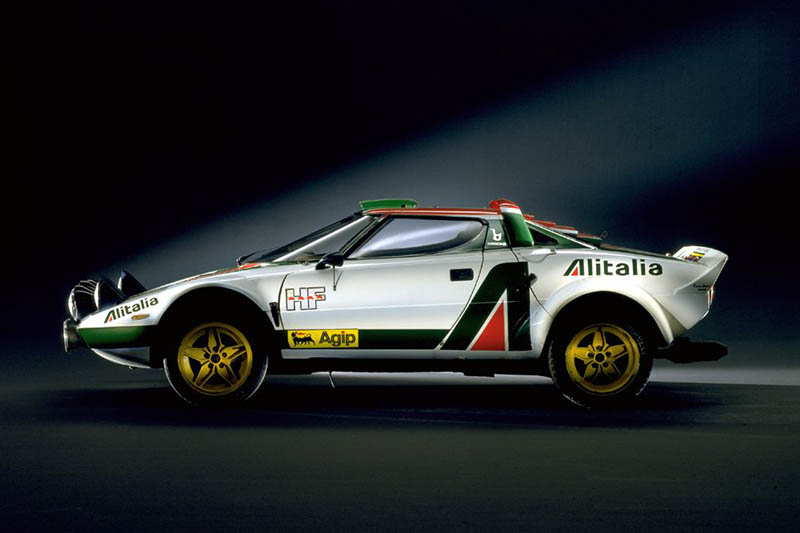

Lancia Stratos

1972

Like the M1 that follows, the Stratos Stradale was a pure homologation special. With the out-there Stratos, Lancia smashed the outmoded opposition in the World Rally Championship for three years running between ’74 and ’76, winning 17 rounds in the process.

The Stratos Zero concept car had been shown off by Lancia back in 1970, a fully sci-fi wedge designed by Bertone that morphed into the Stratos HF of ’71. The production version retained the wraparound windscreen and wedge shape, and although the new HF toned down the more extreme aspects of the Zero (also design by Miura and Countach maesto Marcello Gandini) it still made everything around it look a decade out of date.

Power for this exotic car came from the Ferrari Dino’s 2.4-litre V6, and with front coilovers, rear MacPhersons and a weight of less than 1,000kg (2,200lb), the Stratos was an exceptional performer. With ‘only’ 190hp, the 60mph sprint still took less than five seconds, and 140mph in top gear pushed it along just fine.

This was a car built primarily to compete, which meant that the Stradale road versions are few and far between: they’re the exception rather than the rule of the 492-odd Stratos that were constructed in period.

BMW M1

1978

The ’70s were drawing to a close as BMW got in on the supercar act with the short-lived and brutal M1. This car is another exception to the rule: the M1 was a deliberate homologation special, made expressly to allow BMW to take on Porsche in sportscar racing.

Lamborghini was originally commissioned by BMW to build the car, though BMW would supply the motor: a fuel-injected, 3.5 litre six-cylinder that featured six throttle bodies and produced 273hp – good for 160mph. However, Lamborghini in ’70s was a less than viable proposition, despite its epic cars, and the Giugiaro-designed supercar was brought in-house for the main production run. Giugiaro would construct the bodies, and BMW would then add mechanicals and finalise the build; less than 500 were built between ’78 and ’81 (only 400 were actually required for homologation).

The M1 used a state of the art spaceframe chassis with a fibreglass body, with the mid-mounted straight-six M88 engine based on the company’s successful M49 unit that had been used in its 3.0 CSL racers.

The M1 spawned not only the fire-breathing, 850hp Group 4 and 5 Le Mans cars, but also the legendary Procar series that pitted contemporary Formula 1 drivers against each other as part of the build-up to the main race. The five fastest F1 drivers from Friday practice (politics and endorsement allowing) would line up against a grid of sportscar and touring car drivers, which made for some amazing racing.

’70s supercars and their concept cousins still play an enormous part in influencing current designs, so it’s not a surprise that manufacturers often hark back to models from that decade with recent concepts – they still look modern. There was a purity and freedom introduced to sportscars that opened up what was acceptable on the road. And the result was pretty much anything goes: as long as it’s fast. We’ll continue to develop that theme in the stories to follow over the next two days. Make sure you join us for exotic drives, a look at the one of the most iconic supercars of all time, the McLaren F1 LM, and looks at the process involved to make a modern supercar.

Jonathan Moore

Instagram: speedhunters_jonathan

jonathan@dev.speedhunters.com

Um... no comment?

...classic...

...classic...