France is rightly regarded as the birthplace of auto racing. At the turn of the 19th century technical innovations might been pouring from the pioneers in neighbouring Germany, but a lot of their interest seemed to be in developing the science rather than their direct practical application. The French on the other hand wanted these new technologies, and wanted them in racing cars. And racing cars meant they needed race tracks. This insatiable thirst means that the country is riddled with the remains of incredible circuits, organic tracks that evolved from the landscape just as the new industry of motor racing was similarly evolving in the workshops around l’Hexagone.

Name any major town in France and it’s likely there was a race track there at some stage. Calais, Bordeaux, Boulogne, Marseilles – they all hosted races at one time or another.

Almost 90 different tracks are on record, some nothing more scratch circuits put together over dirt tracks linking small towns. But as roads became more permanent, French tracks became etched into the annals of motor racing history: Le Mans, Reims, Rouen – and the Charade circuit at Clermont-Ferrand.

Clermont-Ferrand is located in the centre of France, deep in the mountainous Massif Central region. The surrounding landscape looks like it’s been forged by Vulcan himself, savagely ripped through by a sawtooth chain of dormant volcanoes.

The Vulcan link is apt: the Michelin rubber company was formed in Clermont Ferrand in 1888, and still has its headquarters there to this day. The black of rubber is matched by the black volcanic rock of the area – the city’s cathedral is a clear case-in-point of the ground it’s built on.

This porous dark matter litters the landscape and would have a dramatic effect on the life of the circuit.

Charade – also known originally as the Circuit Louis Rosier – might not be the oldest in France by any means, but it followed the country’s fine tradition of taking epic local roadways to make a phenomenal racing circuit. The first layout was mooted as far back as 1908, planned to run around the huge local volcano of Puy De Dôme, and a street race around the town itself was scheduled for 1955.

The former never quite came to fruition, and the latter was cancelled following the disaster at Le Mans that year. But the the plan was rekindled just a couple of years later, with the idea of a unique mountain layout to provide a true test of man and machine.

How big and imposing was the track? Well, the size of Charade’s outline is clear to see from the aerial view above.

The French motorsport federation picked out the route using local roads. A couple of different iterations were investigated, including a 12km behemoth that passed through three local villages, before they settled on an 8km layout that picked its way around the high ground overlooking Clermont-Ferrand.

Each of the alternatives used the same north-eastern section, which passed through the village of Charade and then looped round the volcanoes of Puy de Charade and Puy de Grave Noire before cutting back down to the finish.

A new dedicated link section was constructed in 1958 to create the new track, which would comprise the last corner, start-line, grandstands and first corner. The rest would be public roads. And what roads…

The track was both respected and feared by the great drivers of the time, as all the best tracks were. The enjoyment they could get from the challenge of using their skill to lift them above the merely good was always tempered by the inherent increase in danger that these fearsome tracks held, just as at Spa-Francorchamps and the Nürburgring.

It was a quick track – Chris Amon’s lap record of 1972 set the bar at an average of 104mph, which is incredible when you study the layout. It was described as a quicker, twister version of the Nürburgring. Drivers even complained of motion sickness and would wear open-faced helmets just in case, though that would have dire consequences.

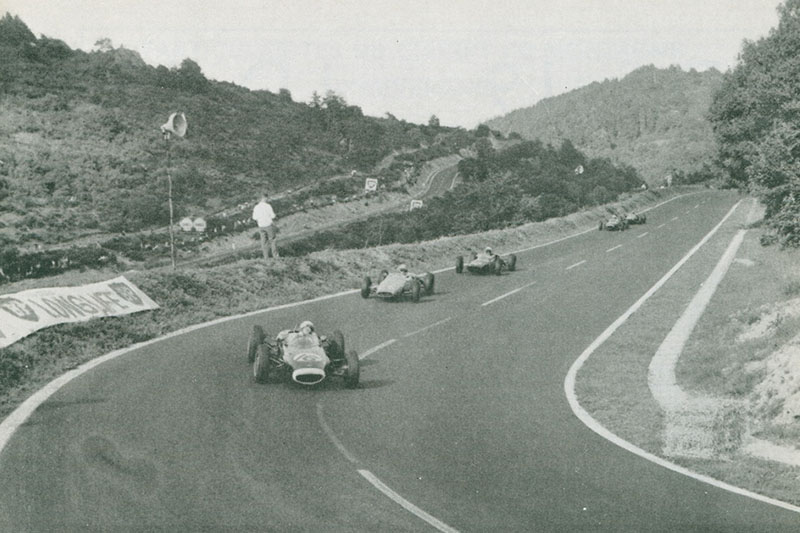

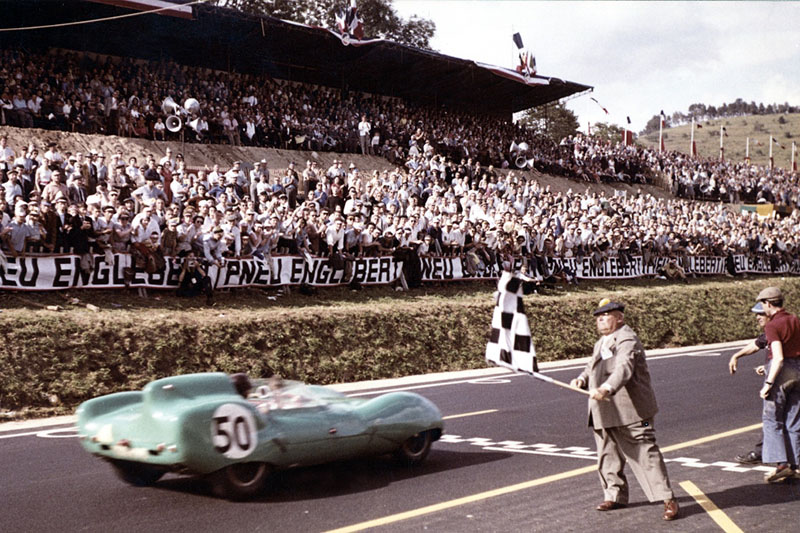

Charade held the French Motorcycle Grand Prix in 1959, and sportscar and single-seater races led up to its first Formula 1 Grand Prix in 1965, which was won by a dominant Jim Clark. In 1966, film director John Frankenheimer used the track for sequences in his classic movie Grand Prix.

Further GPs were held at Clermont-Ferrand in 1969 (Jackie Stewart taking victory in his Matra MS80), 1970 (Jochen Rindt, Lotus 72) and finally in 1972, when Stewart won again, this time in his Tyrell 003. The ’72 race was also infamous for ending the racing career of budding Austrian F1 driver Helmut Marko, now of course head of Red Bull’s driver programme. A stone hit Marko in the face, blinding him in the left eye; a similar incident had happened before to Rindt, though luckily without serious injury.

Stones caused 10 other punctures during that year’s GP, which was not uncommon at the track: the harsh environment was both Charade’s positive and negative. The narrow, rollercoaster roads were incredible, but the volcanic debris that littered the area was a constant problem.

International racing declined over the next decade as concerns about the public roads’ dangerous nature rose. In 1980 three marshals were killed during a touring car race, and the long track’s use came to an end in 1988. With the natural topography preventing any chance of adding run-off, the 8km track was closed.

However, that thankfully wasn’t the end of racing at Clermont-Ferrand. Retaining the original southern portion of the track, a shorter, modern track was constructed which is still in use to this day, hosting national race series, track days and driving courses. But best of all, the old layout simply reverted to type: back to public roads that can – and are – still enjoyed.

Starting back at the pits, the start of the Circuit Louis Rosier rolls gently downhill…

… before entering a fast left-hander. The cars would then stream uphill en masse to the second corner at the crest, Manson, and onto the D5F public road.

A concrete wall here at the edge stopped cars tumbling off the precipice and onto the local road to the village of Charade.

The cars continued accelerating through a flat-out left kink and up to a blind brow, with Charade on the left as the speed rose.

A small kink followed, then a short straight down to the Belvedere complex.

Looking at the map, you’d think that this was perhaps the most challenging part of the circuit: a medium-speed hairpin with the entry compromised by this curving drop, but this was nothing compared to what would follow.

However, the hairpin obviously provides an ideal location for more modern machinery!

Exiting the hairpin, the speed rises, the road drops away and the challenge just gets bigger. Two fast downhill lefts lead into a fearsome sequence of corners.

Get a turn wrong, and the ‘run-off’ is vertical and made of stone, vertical and made of air…

… or consists of a volcano.

Les Jumeaux is a tight right-left-right followed by a quick left-right-left sequence. It’s a stunning section to drive even within the speed limit. The names means ‘twins’, and you can see why: two seemingly identical corner entries in quick succession, but one with a slow exit and the other fast.

Imagine this in a Lotus 72… Fighting the camber and with the rear trying to break away, the balance of brake and throttle, minuscule barriers between you and sheer drops. Getting the flow through here would have been crucial.

http://youtu.be/NgPKzCJzdtY

In fact, check this clip from the ’72 race for a flavour (and here’s an extended version).

It just doesn’t seem to end. You feel dizzy in a modern road car, so I can well believe the effect it had on drivers of F1 cars.

As I was walking this section, I found the broken remains of a key fob from a rental firm. I wondered where the rest of the rental car was…

When you break out of Les Jumeaux, the descent hasn’t ended: there’s a short blast downhill before the seriously deceptive and hugely challenging double-right of Gravenoire at the lowest part of the track, overlooking the town. The entry and first apex is fast, but the second apex comes up almost immediately and is far tighter and slower. Maintaining speed would have been crucial though…

… as from that point the road changes character. Power would have been everything, for a two-kilometre push back uphill.

Left, left, left, right… keeping the throttle pressed down, drifting the car through the kinks.

At this point, the Carrefour de Champeaux is where the old track is cut. The D767 branches off right and left, with the original line of the track plunging on straight ahead.

Now rocks bar the road, and a gate prevents access to the modern track perimeter.

But on the other side, this link snakes down a slope…

…before we get to the point where the modern track joins from camera right. Through the Virage De La Ferme left, a long (for Charade) actual straight piece of road continues the gentle descent.

Le Petit Point was the one piece of road that didn’t follow nature: here the track artificially bridged the apex of the v-shaped valley.

After the rush of speed, the final section of track is a series of fluid switchbacks and arcs that leave you punch-drunk.

Whereas from Gravenoire the power could be applied in a straight line, here the car is never straight, meaning that even now the surface is covered in black lines.

Then as now, this is a favourite place to spectate.

Tertre De Thèdes follows, a majestic swoop of a carousel curve that rises up to a zenith before rolling downhill again.

And yet it’s still not over! There’s never timer to relax: a fast cambered left pitches you into the last corner…

…the parabolic hairpin that will try its best to throw you into the volcanic gravel that surrounds it.

http://youtu.be/UbEsNSGy3bI

What does all that look like when put together? Well, in a deliberate effort to share the motion sickness, here’s some raw video of a lap around the track, in double-time to give more of a sense of speed (and so you can’t hear me constantly going on about how amazing the road is).

So to the modern track, which utilises the amazing final part of the old track, and adds in a Sears Point-esque opener followed by Bathurst-like dipper. Basically it’s the section in this image that’s above the word Charade.

When they designed the shorter track, they certainly kept to the spirit of the grand old track that surrounded it.

A series of tight chicanes and blind rising and falling sweepers that are in tune with the rhythm of the original.

http://youtu.be/A8EnG_JQsrA

An exploratory lap at medium speed was enough to get a taste of this stunning layout – and to make myself promise to return for a turn in a proper car at racing speed as soon as I can.

Thankfully the historic layout is unlikely to be erased in the manner of tracks like Rouen, perched as it is up high in the mountains and away from petty-minded scrutiny, and its public roads can still be enjoyed at leisure. The current Charade track? It’s is a hidden jewel among Europe’s great racing circuits, as much a mini-Nürburgring as ever. I’ll be back there as soon as I can, and Charade should be on everyone’s must-drive list.

Jonathan Moore

Instagram: speedhunters_jonathan

jonathan@speedhunters.com

The first ever race at Charade:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pvIDfqP8pIU

Caro Jonathan, muito bom seu post sobre Clermont, caso me autorize gostaria de reproduzir m meu blog HISTÓRIAS QUE VIVEMOS, aguardo sua autorização. Parabéns.

Rui Amaral Jr

todays tracks are boring large go kart tracks and this old circuit could be reopend as it is no less dangerous than the old nurburgring.

jonathan poole The modern track is open. There are races as well as track days on it. Feels a bit like a short Nürburgring.

The old track was mainly constituted of an open road (which is....open today).

Nicolas Schmit jonathan poole well the tt races are on open roads and I think people would love racing on the old circuit here, also charade is a shadow of its former glory. I cant believe what they did to rouen either. motorsport doesn't care about the historic tracks that could still hold racing and are more of a challenge than the new ones.

jonathan poole I guess you should check hill climbing then.

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Col_de_la_Croix_Saint-Robert

If the Nürburgring Nordschleife is still open for public lapping, surely that could work on the old Charade Circuit. And hey, why not a 24-hour race on that layout in the vain of the Nürburgring 24-hour? Not with as many cars, of course. But it could work.

Jonathan Moore InnerToxicity charles Agreed. In fact, I think future Gran Turismo and Forza Motorsport installments should include both old and new version of Charade. That would be just epic!

Nicolas Schmit jonathan poole Mount Panorama Circuit is all public roads with little runoff area in the section on the mountain. If that place can still hosts races, how hard can it be to run any on the old Charade layout? And if the Nürburgring can do it, so can classic Charade.

I've been there two times, excellent track and nice backcountry for you vacations.