Plastic covers and even carpet cover modern engine bays; they’re a barely concealed no entry sign. You are not welcome. There’s a glorious technological openness about older cars, and especially vintage automobiles. You open a bonnet and might get spattered with oil, but you’ll see an engine in its rawest form. But the problem with particularly old cars of the ’50s and ’60 is that even the road versions were never really designed to be driven for any significant distance. You wouldn’t expect to drive your XK to Paris and back without expecting to have to rebuild it the minute you got back (if you got back…), and your car would be downing as much oil as you were wine…

JD Classics are one of a handful of companies who specialise in complete rebuilds of classic road and racing engines, taking venerable old units and not just making them breath again but improving on the original designs in the process.

It’s often hard work, as much investigative process and complex jigsaw puzzle as it is engineering project… If modern engines rely heavily on computing know-how, classic engines require serious engineering skill combined with an emotional investment. Aural and tactile senses come as much into play as physical effort.

A help is that with classic cars so popular, an international network of specialists has grown up that supports and manufacturers original parts using modern materials and techniques, backing up the local expertise and allowing for not just straight rebuilds but dramatic improvements in quality. Old might not always be best, but JD Classics take pride in making the old better.

Piff Smith is one of the specialist engine builders at JD: they have a small team…

… but a frightening number of engines to deal with.

The bread and butter for the team is the XK straight-six in its various iterations, from the first 3.4-litre blocks first built back in 1949 that powered the eponymous XK sportscars, through the evolutions of the ’60s and ’70s and on to the 1990s. The basic XK inline-six platform concept continued all the way through to the 4.2-litre that was used in the XJ Jag saloons of the ’90s and even powered military vehicles like the Scorpion and Scimitar armoured recon light tanks.

There are then half a dozen or more variants of each size engine, although often a number of parts can be interchanged between engines with a bit of minor modifying, such as timing chains, cranks, rods and pistons, which means keeping old engines running is a little bit easier. Piff and co seemed to have an example of most of them as well…

The racing side of things is as cutting edge now as it was back in period: interestingly, even as early as the ’50s materials like titanium were being used, though racing crankshafts could still weigh 35kg. Individual engines could evolve in unique directions, so the JD Classics team tend to design and manufacture in-house bespoke smaller parts for competition, whilst commissioning outside specialist firms to manufacturer larger parts such as cranks, conrods, pistons and cylinder heads.

This is where the individual specialities of Piff and his colleagues comes in. For instance, Piff’s experience prior to joining JD Classics involved working for various racing programmes in the ’90s, including Ford RS200 rallycross cars, Nissan’s British Touring Car Championship SuperTouring squad and the engines for RML’s MG Le Mans prototype. Although by his own admission, Piff says that his engine knowledge is a decade out of date, it does mean that he worked on some of the last major engine programmes before electronics began to take over – and some of the best. Nissan’s SR20 was eventually pushing out 320hp in the BTCC, and exotic materials and coatings were becoming commonplace, as well as advanced machining techniques.

This knowledge is now ported to the vintage engines JD Classics specialise in. Using improved belt or chain-driven timing and chain tensioners are just some of the tricks it uses to bring new performance to old Big Cats. SuperTouring technology on an E-Type? You’ve got it. JD has redesigned the valve train and camshafts, and is working on a new crank: it’s all about introducing reliability and improving efficiency without losing the spirit of the car.

Replacement forged pistons can now be bought off the shelf that utilise modern lightweight materials, meaning better sealing and lower fluids consumption. It’s a virtuous circle that means that cars can roll out of the JD Classics workshop and straight into long-distance competition. A restored MkVII Jaguar took part in a recent Mille Miglia without any need for an oil top-up.

Work on an engine often starts behind the driving seat rather than in the engine bay, with a test run by an engineer to get a feel for how an engine actually drives on the road. The next stage is when the block is hauled up from the workshop below, often directly from the car (though this was an XK block being winched down: the Toyota 2000GT’s engine was already apart and being worked on).

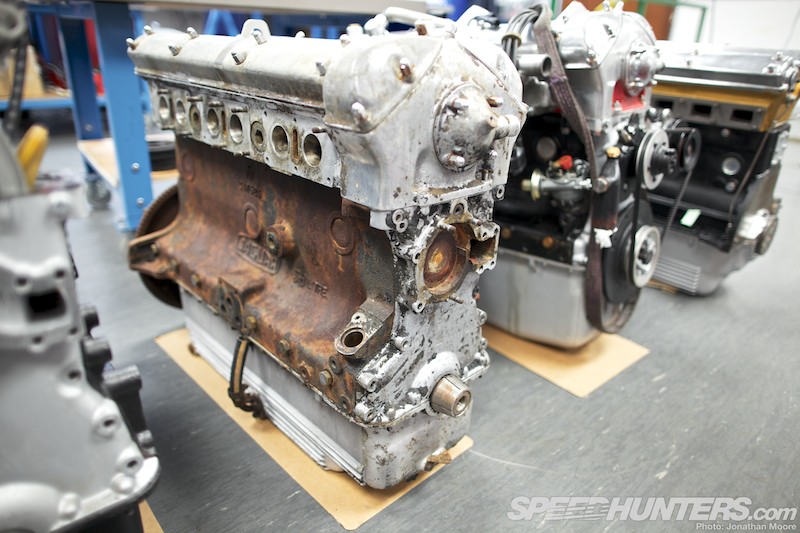

There’s then a triage phase, where priorities are decided and engines lined up ready for work. The workshop really is awash with an intimidating number of patients-in-waiting.

Engines which look beyond repair to the untrained eye can often still be salvaged…

… even ones where the block has been punched through by an errant rod. Although the cause of an engine failure can seem pretty obvious, as with this barn-find, typically the problems only become apparent the deeper you delve.

And this is where the team’s decades of knowledge comes in.

There are three main bays for Piff and the team – each engineer has a separate working area, and are often working on several projects at once. JD Classics has a number of different strings to their bow, so the engine team have to support the racing department, sales and customer projects.

Time is their biggest enemy, from both the damage it does to engines and the lack thereof to complete projects.

Taking stuff apart is easy: putting it all back together is where things get tricky, especially with engines where they may be little or no surviving documentation. A digital camera is their friend from the start, allowing the team to keep a track of each project as it progresses.

Even seemingly tedious tasks like cleaning are fundamentally important. There are several cleaning stations which used parrafin-based solvents, and the team prefer to do all their own cleaning. It keeps a connection with the parts they’re working on and also helps the learning process.

Piff’s main project during my visit was an inline-six from an Aston Martin DB2/4. It was a typical example of what the team have to deal with, where the initial diagnosis only revealed the tip of the problem. The car had come in with a report of a water leak; the road test revealed that the engine sounded harsh and a little tired. These I6s were designed by Lagonda for a much more sedate life than they typically ended up with, and fitted into bigger GTs, they frequently had problems with recessing valves.

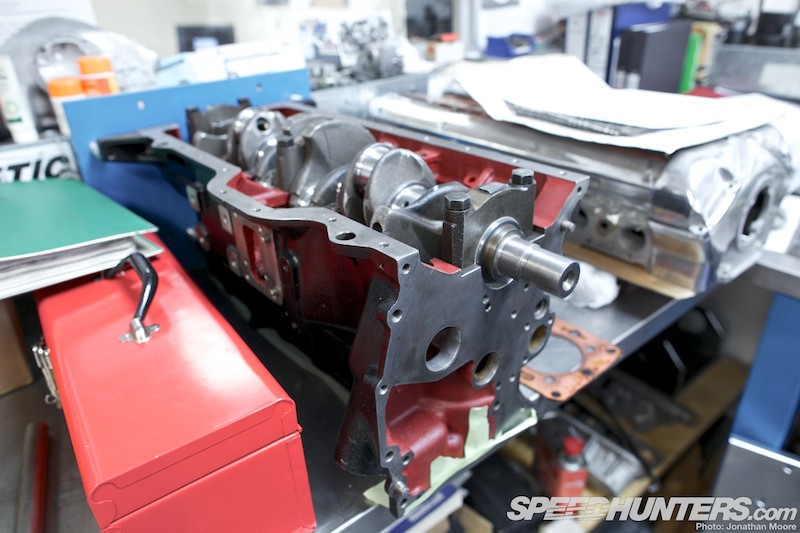

The engine had been split and secured to a jig, where it could be properly examined and worked on – it was actually approaching the final phase of its repair. There’s a mechanical beauty when the engine is stripped of all its ancillaries and the internals laid bare, so you can see the spaces where the seemingly impossible takes place, the interaction of fragile components in the face of explosive force.

As Piff had worked through the initial issue – a replacement head gasket hadn’t fixed the problem and had shown that the liners were being scored as it ran – it became clear that this poor engine really needed serious surgery. The block deck was no longer parallel to the crankshaft axis, and the liners weren’t on an even plane. Effectively all the internals were out of kilter.

The main iron block had to be completely refurbished and the main surfaces remachined; the decision was taken early with the owner to buy a brand new cylinder head. Although the original part could be repaired, with these veteran parts you’re talking about a piece of metal that’s almost pushing human retirement age, let alone mechanical. The amount you could spend on refettling an original is more often than not better spent on a new part unless the heritage of the car demands complete authenticity – such as with Clark Gable’s XK120 that JD recently restored. Piff did stay true to the look of the engine itself, which has been freshly painted: the colour’s official name is David Brown Hunting Pink!

Measurements are crucial: even in old engines tolerances are small, with valves packed in tightly with little or no space for error. Again, using their own expertise often provides a new direction to try, and Piff has come up with his own special solution for the AM’s perennial problem of oil and water mixing based on his LMP experience, which is to do with the liner not seating properly in the block; soft copper being part of the issue.

This leads onto a big question for the restoration of classic cars, and the purist view about what ‘original’ actually means. Piff and his team will always try and advise following the sensible and practical approach: salvage what original parts you can, obviously starting with the block, but then replace, modify and remanufacture where possible, using modern materials if applicable.

It’s important to remember – and again, something the particularly zealous might not like – but old cars often really don’t drive very well. They could be difficult, uncomfortable lumps to drive, with engines that were organic entities requiring a strange combination of finesse on the one hand and brute force on the other.

There’s a delicate line to tread with the mechanicals of these old engines, with the age and previous maintenance usually the directing force in deciding what remedy can be applied. Sometimes there’s simply no more metal on a valve to even up seating, or you’re working with original parts that are so thin that they’ll bend with the slightest pressure in the wrong direction.

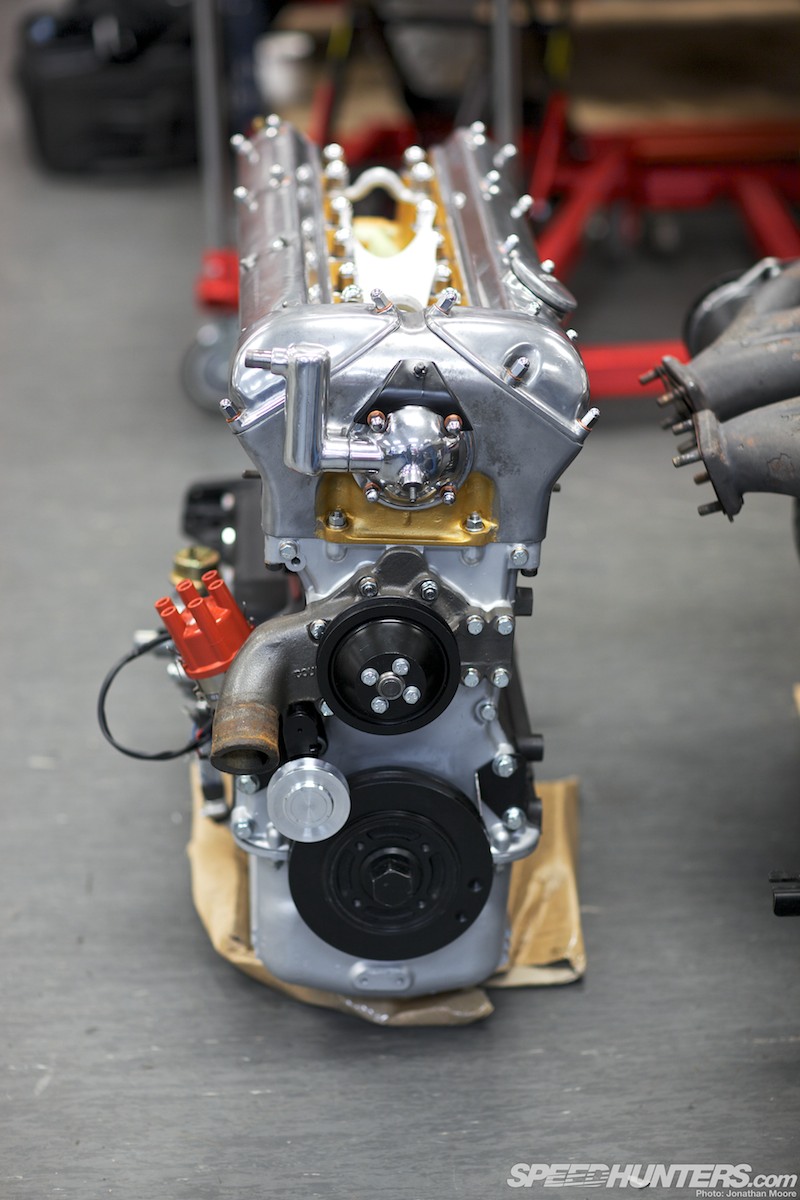

The 2000GT has been an on-off project for quite some time, but it’s also been seeing the benefits of some modern improvements that will make the Toyota sing even sweeter than in period. The team have been gathering data from where they can to help them with the engine rebuild, which though missing documentation was at least a relatively conventional straight six. As seems to often be the case, it’s experience that starts off the process even with an unknown engine: you know basic clearances and interactions, which you use as a staring point to begin the restoration. The head and gaskets were gleaming…

… with the block and crank freshly restored and the inside painted with a protective coating. This project was about four weeks from completion. Again, it seemed to be timing where the real difference could be made. For the Toyota, Piff had designed and manufactured a replacement chain guide out of Peek. The original spent as much time thrashing about against the underside of the cam than doing good work, so Piff prototyped a new part, using a pivot to replicate the spring effect of the original part whilst extending the length so it provides even greater support.

As someone who struggles with patience at the simplest thing, I was intrigued by the in-depth process required to create a part like this. Piff started with sketches and a cardboard template, then moved to bending up some aluminium before creating a jig and template to cast the plastic component, which now features countersunk screws. More SuperTouring technology! He’s also redesigned the tappets to make them lighter in a constant process of prototyping and refinement.

On a table in the middle of the workshop was this kit of parts for a Porsche Type 547 quad-cam flat four, taken out of the 550 Spyder that JD run for a customer. It’s the only surviving Spyder with its original configuration flat-four. Somehow all these bits needed to go back together…

… and then fit inside the crank case that was waiting on the parts shelf. The case splits in half, with the core then dropped into one half before being reassembled.

The engine can only be taken apart and put back together twice in a day, and bespoke tools had to be made to help the process which included a small 700Nm hydraulic jack with just 19mm of travel to undo the main nuts holding everything together. To make things even more confusing, the main bolt had an equally pitched connecting bolt, so one with a fine thread and the other coarse, rotating inside each other. You have to wind one a certain amount, then wind it back, and the coarse thread pulls the fine one to it. Making the tools took a couple of weeks alone, before restoration could even begin… It sometimes seems more like safe cracking than engine work!

It still ran a roller-bearing crank, which was the owner’s choice, as many have been converted to a flat plain crank. This was a phenomenally complex engine even at the time, with its interlinked mechanicals making for a hellishly difficult task when it came to maintenance – and even set-up. Assembly time was quoted at 120 hours, and even configuring the timing could literally take a day, as like a devious puzzle every alteration would affect another part of the engine.

There are lots of little shims around each part that have to be split; they move the gears in and out to get them in the correct mesh with each other. It can take a week to assemble a single head, which then needs to fit together against the other heads, axle and diff. The engine is designed to run with no perceptible backlash, which means everything has to be tight, but not too tight. It just sounds like a nightmare…

The most modern cars that JD work on are Group C sportscars from the early ’90s: even with these more recent cars improvements can be made to help with reliability and performance. Spare parts for several of its C1s were stocked up, and its XJR11 had been boosted with a newly designed oil pump to replace the original that was mounted up high in the engine’s V, and the rods and pistons replaced. The latter were two-piece castings from Maler, based on an old Porsche design where the oil would be squirted directly into the head, something that Piff also tried to integrate on rallycross RS200s.

Even a bit of V8 firepower got a look-in, though amusingly the team are less than keen on the big V8s, preferring the more subtle grace of the straight-sixes they’re used to dealing with! This was a Chrysler unit from an Allard J2, and a couple of other Chevy and Ford blocks were in the triage corridor outside.

JD Classics has an impressive collection of Samuri S30s in its care as well, and various parts where stored on another shelf. It recently bought a stock of spare parts, and sacrificed some of the components to solve ongoing water leaks it had been experiencing on the racecars.

A block was cut up across several axis so the team could investigate: inside they found that the original plumbing just wasn’t that efficient, with several narrow apertures for air pockets to form. Piff and the crew are now adding in bleeds in the water gallery to keep the flow open. It’s yet another example of how they think outside the box to solve old problems with old engines in a new and innovative way.

Jonathan Moore

Instagram: speedhunters_jonathan

jonathan@speedhunters.com

I do own and drive a car but when it comes to its engines and technicalities, I would rather seek advices from the professionals in the automobile industry. It is similar to the plumbing works we all have back at home. We might be able to fix a thing or two that are visible from the surface, but when it concerns the piping works underneath that sink, nobody dares to touch anything to prevent worst circumstances.